By Steve Dawson

Standing in the riverbank looking at our 30ft canoe folded nearly in half over a log in the water, our race was over before it had begun.

It had taken a year of planning and preparation to get us to this nondescript sandbar on the banks of the Blanco River four miles from the starting point of our first paddle together and a mile from where Dick and Tom, our support team, were waiting for us at Luling Sandbank. In another half an hour, they would probably start wondering why we hadn’t turned up. Maybe the gear that we lost from the boat would float past and give them a hint that something had gone sideways.

Our first paddle together as a team had started out so well. It was a week before the race, and we’d put the canoe into the water on the Blanco for a shakedown paddle. Everybody had settled in nicely. Dave Carlson from Austin TX was in seat one. I was in two with Kate in three and Mike Dey from Schertz TX in four with the steering.

We’d been getting a feel for the boat which was uniquely Texan in design. Thirty feet long and built heavy from carbon fibre. A canoe with a rudder, designed to be used interchangeably with either single or double blades paddles. A Texas Water Safari Unlimited class boat, anything goes, as long as it goes fast.

Veronica’s Corner was where our unfamiliar team had come unstuck. A right turn leading to a left turn, with fallen trees blocking most of the river. There were three paths through. Left was a shallow channel on the inside of the bend. Far right, the channel was too narrow for the 30 foot boat to negotiate the curve of the bend. The centre channel was clear but the water flowed straight into the branches of the tree.

A moment of indecision between left and centre lined the boat up side on to the upright log that divided the two channels. Dave and I were heading left to run the shallow water or at worst run it aground and drag the boat across the gravel. In the back, Mike had decided to dismount and manhandle the boat in the thigh deep water.

Dave and I were still pulling when Mike jumped overboard. The boat skidded into the upright log, dipping the upstream edge of the boat and scooping water over the gunwale. We hit the upright log with the boat starting to swamp and three of us still seated. Mike had no chance of holding the stern out of the current after that. Kate had followed Mike over the side, but Dave and I were still trying to reach the beach on the left. We abandoned ship as the current flipped the boat past it’s terminal stability and onto its side against the log.

There was a sound like somebody snapping a bundle of twigs, and our race was over.

Kate and I had flown 14,500 kilometres to race the 2019 Texas Water Safari, and now we were spectators. We also owned half a boat, conveniently portioned so we could take our half home.

Self pity and blame then took a back seat to the more pressing problem of how we get the boat off the tree, and how we would get it to the takeout, about a mile downriver. That would require several phone calls to locals to find out who’s property we were about to trespass across, and where we could find somebody with enough duct tape to stick a boat back together. We should also let Dick and Tom know that we were OK.

Traversing the river back upstream was an opportunity for Mike to point out the poison ivy growing on the riverbank. “Three green leaves and red stems is the one to avoid”. More often that took the form of “You’re standing on poison ivy”.

The Texas countryside is different to what we are used to. It’s farmland, but not the regular pastures that we are used to seeing in Australia and New Zealand. The ground is rough, and weedy. Pecan trees line the river banks. It took us a while to work that one out as the local pronunciation is P’caahn. The sound of oil pumps squeaks across the countryside. It’s oil country. Oil literally seeps up out of the ground, and the smell of crude wafts in the air around Luling.

We backtracked about a mile upriver, crossing from side to side, climbing over log jams left by floods, observing that they would probably be good places to find a snake or two. Locally, Cottonmouths are the chief concern. Not naturally aggressive, unless cornered or stepped on.

Later that day, we’d have a conversation about the race’s mandatory snake bite kits. Essentially spring loaded syringes to suck the poison out of a snake bite, just like in the movies. Very different to Australia where the protocol is to apply a compression bandage above the wound, wrapping down over the wound, then immobilising the patient and keeping the venom from spreading through tissue until they can be treated at a hospital with anti venom. We decided that we’d probably do it our way if we were bitten.

As we scrambled along the bank, Mike had managed to contact Victoria, a paddler with a piece of land adjacent to the river who met us at her boundary line with some ratchet straps and a roll of duct tape.

Returning to the boat we used some saplings as splints, secured with the ratchet straps to get the broken halves of boat realigned, and then liberally applied duct tape to the gaping tears in the hull until it looked passably watertight. There was no way it was going to support the weight of paddlers. We would have to swim it out. At least it was floating.

The Safari rules don’t require life jackets to be worn until you reach the saltwater barrier which is just before crossing the bay to the finish line. Much of the river is shallow. The conditions are almost always horrendously hot, and the added bulk is an impediment to portaging through the log jams. You are required to carry them in the boat for the entire race, so stowed size is important. When we arrived in San Antonio, we’d stopped in at a sporting goods store and spent a whole $25 each on the cheapest horse shoe style life jackets that they had.

We were now wearing those $25 lifejackets as we swam beside the boat. The difference between these cheap life jackets and the racing life jackets I normally use became obvious as soon as I stepped into water over my head. The cheap jackets rode straight up until it was around my neck, choking me unless I was lying passive on my back. Every time I tried to swim freestyle through a pool, it would try to roll me over or choke me. Eventually I discovered the best way was to roll onto my back and kick while pulling the bow rope behind me. We walked, waded, scrambled, and swam the boat along the river in silence, contemplating what this meant for our race hopes.

We made pretty good progress, right up to the point where the takeout came into view. The last 200 metres was a deep pool that we needed to swim across. There were maybe a hundred people gathered on the sand bar to enjoy a hot day out on the river. There were marquees, lawn chairs, music, and a large crowd of people to witness our arrival. It was a fair bet that they had all spent the day sitting in the sun, drinking beer.

The river gods, not content that we had to swim side crawl, towing our broken canoe across 200 metres of deep water, added an eddy current that did its best to recirculate us back upstream so the crowd would get more than one look at the four idiots in red lifejackets bobbing beside their canoe.

Dick and Tom were pretty shocked at what we’d managed to do to the boat in such a short time. The amount of structural damage became woefully obvious when we lifted it onto the roof of Dick’s van and the nose sagged to the ground while the back lay straight on the roof. This was despite the splints and straps we had applied.

Meanwhile Mike had been making calls to John Bugge (pronounced boogie), the boat builder we’d rented the boat from. The essence of the discussion was that we were bringing the boat in with some major damage. John would take a look and give us a rundown on what it would take to fix the boat in time to race it on Saturday.

John already had a shed full of work stacked up for other people and not enough time to do an extensive repair on our boat. He gave us an estimate of 100 hours of repair work. Amazingly, he said it was possible if we were prepared to do all of the rough work of stripping the fittings, cutting out the broken parts, sanding all of the surfaces so the eight foot section of shattered hull could be rebuilt.

We didn’t hesitate in committing to doing as much work as it would take to get the boat back together for the race. Without the boat, we had nothing better to do.

Johns assessment of the boat? It was the most damage he’d seen done to any boat, that still bore a chance of being repaired.It had to go back into the mould in order to align the two halves. Without the mould, it would have been nearly impossible to get the boat straight again.

John also told us that we were the thirteenth boat to wreck on that log at Veronica’s corner in pre-race practice this season. Veronica’s boat was currently on the other rack with its own repairs just being finished off. It had been a good season for boat repairs.

We got a chance to meet Veronica of Veronica’s Corner fame a few days later when she came to collect her boat. I pitched the idea that as we’d done more damage to our boat, we should be able to lay a claim on naming rights. She smiled and said “I’ve broken my boat there twice!”. Veronica’s Corner it is.

The days that followed were full of cutting, sanding, and sweating in the Texas heat, as we prepped the boat for John to layer in the repaired sections and stitch our shattered ride back together. Each morning we would drive out to his workshop, grabbing some breakfast tacos on the way, sand until there was nothing left to sand, and then head back to our base at Mike’s place, itching from the carbon fibre dust that had covered us from head to toe.

There was plenty of talk during our time in John’s workshop. John Bugge is a TWS hall of fame paddler, and the only paddler to have completed 40 safaris. He had plenty of good tips and advice for us to absorb. It was also fascinating to compare the construction of his Safari boats with the construction we are familiar with in Australia.

Safari boats are built tough and heavy, designed to run into obstacles head on, and either punch through, or run up over them. The only reason we’d managed to damage his boat, according to John, was that we’d broadsided the log and stressed the boat in the only direction where it is weak (relatively). Our empty boat weighed in at around 55kg despite being full carbon fibre. After sanding and repairs, we suspected it may have actually been lighter than it was when we started, after finding that the foam core in the floor was soaked with water.

We managed to sneak in a couple of scouting paddles between sanding sessions, and while John relaminated sections of the hull, bulkheads, and seat mounts. We took two of Mike’s aluminum tandems from the start at Spring Lake to Staples Dam, and then from Staples Dam to the low bridge at Spencer Boatworks. That gave Kate and me an opportunity to see the major obstacles we would have to portage and plan which side of the river we needed to be on for each one. We had a clean run through Cottonseed rapid even though both boats got hung up on a barely submerged rock and collided like bumper cars on the approach.

Three days later, John had worked a miracle. The hull was back together, we had new bulkheads installed, all of the seats were back in and realigned, and seat three had been converted to a sliding seat which would allow us to trim the boat better by moving Kate around until the boat ran level. In the race to be ready for the race, we had crossed the finish line and we all celebrated with a cold beer.

That setback had left us with 48 hours to scout a couple of river sections and finish (re)fitting the boat with pumps, food bags, water bottle holders, and other fittings we would need for the race ahead. We then had to get it to San Marcos for registration and equipment check on the day prior to the race.

Back at Mike’s place that night, we unrolled the stickers Mike had custom ordered for our boat. Luckily, we hadn’t fitted them before the crash because the section where they fitted was the section that had been completely replaced. Just to prove the gods were not yet completely on our side, the stickers had been cut in reverse. We laughed and applied them anyway. It would be confusing for somebody in a couple of days.

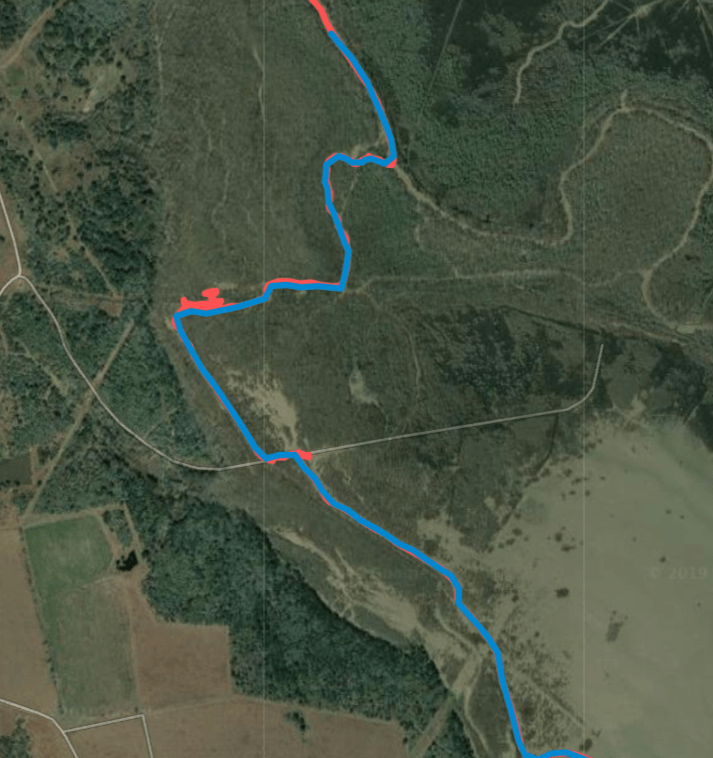

We had one last scouting run to do. We needed to explore Cowboy Cut where teams can leave the main Guadalupe River upstream of a notorious log jam, drag their boats up a muddy river bank, through 150m of trees, mud and swamp, to get to a ditch that feeds into Alligator Lake, which in turn flows back out onto the Guadalupe a few miles past the log jam. The choice to use the shortcut is the choice between a longer flatwater paddle with one large log jam to negotiate, and the shortcut where you risk getting lots in a swamp with no clear way through. Get it right and you can save a lot of time. Get it wrong and you could get lost in there for an hour, or longer. Our scouting trip was to map the correct course on our GPSs in so that we would know where to turn when we came back during the race. Even in daylight without the burden of exhaustion, we made two wrong turns and had to backtrack. Next time we passed through we would be exhausted and possibly delirious. If we were on track for our target time, it would be dark.

Scouting complete, we were ready to race…

Registration Day…

It had been a long night getting equipment ready and checked off against the equipment required for the race. The registration officials check off all the equipment that needs to be in the boat as well as a list of everything we carried to ensure that we hadn’t received any outside assistance during the race. The only things that can come into the boat during the race are food, water, and medical supplies. Everything else we needed would be in the boat at the start line.

Registration is the same for most events. The TWS registrations at Spring Lake is a lot of standing around waiting for officials while you catch up with old friends and meet new people. With so much equipment to be checked in the boats, teams set up in the park and officials come to you. Not what we are used to in Australia where boats are taken to the officials for scrutineering. Most of the TWS boats are simply too big and too heavy to efficiently carry around on a hot day..

The organisers had set up a couple of large marquees for shade from the heat of the sun. Registration was a quick process, followed by a short wait for the pre-race briefing. We’d opted to arrive late to avoid too much time sweltering in the sun. The spaces under the marquees were all taken so we set up under a shady tree nearby.

The equipment check was quick and efficient. We handed the official a list of our equipment. He asked to see specific items of mandatory equipment. Then he took our signed waivers, wished us well and moved on to the next boat.

With another hour to wait for the race briefing, we wandered around looking at the setup of other teams boats. The Safari can be raced in virtually any human powered craft and that pretty much described the array of boats set up in the park for registration. There were lots of aluminum tandem canoes, which race in their own class for the Safari, kayaks of all shapes and sizes, canoes in every form from recreational singles, through pro-boats, and the giant 30 to 40 foot unlimited class that were would be racing.

The largest canoes are the six man Safari boats, 40 feet long with all the paddlers inline. In the unlimited class the paddlers can switch between single and double blades paddles for efficiency or to cycle through a different set of tired muscles for a while.

There used to be a 9-man unlimited but a rule change now limits the unlimited class to 6-man and the 55ft monsters of speed will not race in the Safari again. While we’d been rebuilding our boat at John Bugges, we’d seen the middle section of the nineman mould which added 15ft to our canoe.

Spotting a red tip epic V8 Double, I was surprised that anyone would try their luck with a lightweight layup. I’d cracked my own red tip Epic at home by tightening the roof rack straps too hard. How would a boat that fragile survive the Safari? Looking more closely I noted that it had been pimped with a layer of heavy carbon fibre on the lower hull. That was more like it.

As Kate and I wandered through the boats, there were already plenty of people who knew who we were, either novelty because we were the Australians (explaining the distinction that we are Kiwis who live in Australia caused some confused looks), or notoriety because we had destroyed our boat and resurrected it less than a week before the race. We joked that our boat should be renamed Lazurus because it had risen from the dead.

Each conversation ended with the same farewell – “See you in Seadrift” – a phrase that wished good racing and good fortune of both teams.

Another source of chatter around registration was a group of UK paddlers who had flown into Texas in the last 24 hours and picked up a boat that had been prepped for them by a local Safari veteran. They were set up beside us and I was even more surprised when I found out that they’d done almost no distance paddling. They were going to attempt the Safari on guts and determination alone. I never saw them again.

The strangest sight at registration was a team with a six man SUP board. There had been a lot of social media discussion about it in the lead up to the race. They’d been working on a design and build for a few months, but it had only recently completed on-Water trials. That had been followed by the hasty addition of an outrigger for stability. We’d run some very narrow paths through log jams on our practice runs and like everybody else, we were wondering how the SUP would navigate those obstacles when it was 2-3 times wider than our canoe which was already scraped the sides in some log jams.

Race briefing was a relaxed affair. There were some presentations for paddlers that had completed enough Safaris to get their names on the Hall of Fame plaque. John Bugge became the first paddler to get his name on the newly added 40 finishes panel.

The race organisers went through the various rules, requirements, and hazards on the river. There were the usual warnings, and the usual questions about specifics of the rules.

Official: “There’s a mandatory portage at XXX”

Racer: “what’s the time penalty if you run it?”

Official: “12 months. You’re disqualified. Seriously it’s dangerous.”

The tree at Veronica’s corner had been removed which was good to hear. We’d come together well as a team in the weeks since our crash, but we were still nervous about the prospect of a rematch.

The various checkpoints and cutoff times were described by the officials. The comment of the day went to the chief official Jay whose assessment of the first cutoff time was “if you can’t make the first cutoff, paddling is not the sport for you”

The details are a blur now, as is often the case on a big event. With Mike and Dave brining river knowledge to the boat, Kate and I only had to concentrate on a handful of the details. For me it was the rules for crossing the bay to Seadrift, where the final cutoff is at 100 hours.

Race briefing complete, we left the boat with the security guards for the night, and headed back to Mike’s place for a nervous night of final preparation.

Race Day…

Dave had summed up the race as “No porcelain till Seadrift”. Accordingly, there was a long queue of people lining up for their last brush with civilisation for 418km (260 miles).

The water in Spring Lake is cool and crystal clear, in contrast to the heat of the sun which was just warming up for the 9am start.

Each of the 176 teams made their way down the stairs to the water. Like many of the teams, we paddled the half mile to the end of the lake to examine the first portage. This was where the boisterous part of the race would begin. From a mass start, there would be no time for the boats to spread out before they reached the first portage around an old water mill dam. It would be a stampede.

There were trees and dense foliage with three rough paths through. We scouted each path, discarded one because the runs were too sharp for our 30ft boat, and prioritised one as our first option, with a backup route if there were too many boats in our way.

Paddling back to our position at the back of starting grid, we passed through most of the field, a visual symphony of boats, costumes, fittings, and humanity.

Front of the grid starting positions are secured by finish position in pre-race which we hadn’t been able to attend. Accordingly, our start position was in row 23 of 26. That meant the fast boats were up the front, with slower boats, and then novices lined up behind. Our mix of locals and out of state paddlers placed us way down the back, like the big kid in class who got held back a few years.

My memory is pretty clear up to that point. Then, as the final minutes ticked off, my attention went to final details, boats around us, and making the boat go fast. The events from the next 260 miles are like broken shards of a stained glass window. There are pieces I can interpret, but there’s little structure to hang them together in the correct sequence.

There was a speech. It was a good and proper speech with the appropriate well wishes. The national anthem was played. There was a prayer for the safety of the paddlers. There weren’t any local politicians making speeches, which is good because nobody wants to listen to a politician when they’re on the start line.

“The next sound you hear will be a horn signalling the start of the race…”

Silence… Anticipation… Focus… The blast of a horn, and we were off!

We’d expected chaos at the start. We were big, fast, and very heavy, compared to the boats around us. We also ran straighter than the short boats in the surging waves created by the boats in front.. Crews charged with adrenaline powered away as if it was a 5km sprint race. The waters churned and boats got turned. Several turned sideways and got sledged by teams too wound up to just back off for a few strokes.

Our strategy was to hold a steady pace, look for gaps, and move up hard when one appeared. Don’t crash the boat, there’s a long way to go. Position on the first half mile isn’t going to mean much. Hours later, we would be clear of boats and free to manoeuvre.

An aluminum tandem bounced off another boat and careened towards us at 45 degrees. I broke my stroke momentarily for a classic rugby fend. Adrenaline probably helped, because without thinking, I’d just deflected a boat weighing 300kgs.

It was only a few minutes before we were at the end of Spring Lake, which is basically just a large pond, looking for a place to approach the bank between the 150 boats that were in front of us.

We drove the nose of the boat head on into the bank and everybody slipped over the side into the water. Dave was about waist deep. I was chest deep. I guessed that Kate and Mike were treading water from the back seats.

When we’d scouted the portages half an hour earlier, the foliage had been dense and there had only been three relatively clear paths through. They’d looked like small animal trails. Now, with 150 teams having passed through in a rush, it looked like a herd of elephants had stampeded through. Everything shorter than shoulder height was now essentially flat including a couple of paddlers who had stumbled in the roots and mud.

Completely ignoring our initial portage plan, we dragged the boat straight through the trees to a small side creek where we jumped back into the boat and powered away to rejoin the chase.

Spring Lake feeds cool clear water into the San Marcos River, which passes through the city dropping over small rapids and crisscrossed by bridges.

Spectators lined the banks, everybody was yelling and cheering. Some were cheering their teams. Some were cheering any team. Others were cheering the madness and the spectacle of it all.

The next drop was Rio Vista Dam, where the tubing operations started on the river. We’d scouted it in tandems while we’d been repairing the boat. It was short and rocky with a concrete terrace on river left. Kate and I would jump out, help drag the boat over the main drop, run ahead on the bank while Dave and Mike would take the lightened boat through the last half to a sandbar under a bridge a few hundred metres downstream.

Debris from capsized boats washed past Kate and I as we waited for our boat to make it through. Many boats had taken the guts and glory option, running the drop and taking their chances at either a faster path, or a yard sale of equipment.

Five miles down and you reach Cummings Dam. A boat ramp on river left leads to a quick drag across a grassy field and down a bank on the other side of the dam. We were through clean and quick.

Approaching the rapid called Cottonseed, a long S-bend run on river right, skipping over a submerged boulder above a right hand bend, then it’s over a small drop running out into a couple of rocks which we needed to avoid. We wanted to cross from right to left to avoid a little island of rocks in the middle of the outflow. That would line us up for the left hand bend in the bottom half of the rapid.

Our entry line was good but we were slowed by another boat in front of us.Now, with no forward speed, our rudder was dead-stick. We crossed too late and capsized on the drop, washing past the rocks and into the eddy in front of a very large crowd.

We scrambled the boat to the rocky river bank, rolled it up onto its side using our knees as support to get the massive weight out of the water. It wasn’t perfect, and there was still water in the boat but we scrambled back in and pushed into the current for the second half of the rapid.

Not perfect proved to be an understatement. We’d thought the electric bilge pumps could drain the rest of the water from the boat, but there was still too much water as we swung into the current. Swinging right towards the current and then hard left into the flow, the weight of the water shifted from side to side, wallowing the boat until the gunwale dipped and off balance, we capsized again. Dave commented later that it was the first time he’d swim twice in Cottonseed, a rapid that was only 250 metres long.

Having chewed us up thoroughly, the rapid spat us out dismissively. While the others had been spat into the eddy, I ducked under the boat to avoid being squashed by a second boat coming down behind us and ended up in the centre of the current, heading south down a creek with a paddle, but no canoe. The water was deep and fast pushing towards the centre of the flow, away from the banks. I wasn’t wearing a lifejacket and was struggling to swim cross current in the fast flow with a canoe paddle in one hand. Each stroke took me further downstream from the others who were busy trying to empty the boat for a second time.

We had three electric bilge pumps and a foot pump in the boat. The electric bilges gave us a high pumping volume as well as spares if one failed. For most of the first day, it seemed that there was always one pump that wasn’t working for some reason or another. One was airlocked, then another stopped pumping, while the first one made a spontaneous recovery.

Back in the boat, the crowds cheering us for providing the free entertainment.

At some point the San Marcos River is joined by the Blanco and the clear water becomes cloudy.

Martindale Dam and the low water bridge were next. I have no clear memory of them. The low bridge hangs just a few feet above the water. With the river running high, there was no clearance under the bridge and it was a mandatory portage, made only slightly more complicated by the root ball of a tree blocking half of the span, and a water pipe across the upstream side a few feet from the concrete bridge. We jammed the boat into the bank, scrambled into the water, up onto the pipe, leapt to the bridge, dragging the boat up over the pipe behind us, nudging a keen photographer as we went. In the 30-40 seconds we were crossing the bridge, Tom and Dick restocked the boat with water and SPIZ.

We were moving up through the field of competitors and the boat was running well.

A short distance downstream, Staples Dam was the first checkpoint and again we had a plan. Drive the boat up to the dam on river left, manhandle the boat over the dam, jump down onto a boulder, then into the water, get back in the boat, and get going.

It was going to plan until Dave dropped off the boulder into the water, crumpling at the knees as he went in. He’d planted his foot on a rock which had rolled, twisting his ankle badly. It was obvious it was bad, but didn’t appear to be broken. He grimaced and jumped back into the boat.

Tom and Dick let us know that we’d moved up to 41st position. It was a great boost to morale in the boat.

Over the next few hours, as bridges and portages fell behind us, we would climb the leaderboard until we were in 20th position coming into Luling 90.

We passed through Veronica’s corner again, where we’d broken our boat just a week earlier. Despite the race officials clearing the main obstruction, there was a silent agreement in the boat that we would take the cowards option and portage the boat through the gravel shallows. We were still itching from sanding carbon fibre all week and nobody wanted to tempt fate.

We must have passed Zedler Dam but it’s lost in the blur.

For most of the first day, there were crowds scattered along the river banks. The biggest crowds assembled at major portages and rapids. There for the spectacle. On the long stretches between features, the locals would come out and set up umbrellas and lawn chairs on the banks, or occasionally in the water where it was cooler, to watch the free show with a few beers.

At one point there were the strangled tones of a bagpipe player atop the river bank serenading us as we stroked past. (Can you serenade with a bagpipe?)

The rapids and portages continued to blur together over the next few hours. I was too unfamiliar with the river to remember which one came where. I’d recognise them visually, remembering the approach plan for what was directly in front of us, but there’s no thread tying them together in my head as I try to recall them.

Staples Dam is one of the largest. You pull up on a concrete platform on right, and there’s a ledge just below the water. Two paddlers run around the side of the dam to the base while the other two push the boat over the buttress. It was the point where Dave’s ankle became noticeable. We’d planned for Dave to be at the top, but his ankle meant we had to switch roles on the fly.

The water at the bottom is too deep to stand up and the boat needs to be pointed downstream to keep it out of the current, so only the tail of the boat is on the shore. First Dave climbed into the stern and walked along the boat to the front seat while we steadied the boat. We all repeated that manoeuvre until Mike was in the stern. When we’d been fitting out the boat, we’d made sure that there was enough room between seats to walk along the hull without tripping over stuff, or standing on a stowed paddle.

Meanwhile Dick and Tom had been restocking our food and water. Snack food were passed into the boat in gallon ziplock bags. An impulsive mix of high calorie food that could be gulped and things that we’d figured we’d be able to stomach late in the race when we would be forcing ourselves to eat to maintain our energy levels. A bottle of SPIZ for each paddler provided our primary fuel in a drinkable form. You could race on SPIZ, but at the end of the first day, we would all be craving some relief from the chocolate and vanilla flavoured food substitute.

Water was supplied in ½ gallon cooler jugs, an attempt to keep the water cool as the heat of the day soared into the mid to high 30s. Each jug came into the boat with a mix of ice and water. When we swapped them out, Tom and Dick would check to see how much ice was left. We couldn’t drink the ice, so the ideal was just enough ice to melt before the next checkpoint.

In the confusion at Staples, with food and bottles being passed along the boat, I mistakenly thought that my SPIZ bottle hadn’t been changed out. I grabbed it from its foam cutout and tossed it to Tom on the shore, realising as I threw it that it was actually heavy enough to be full and the guys had swapped it while I wasn’t looking. Bugger! No SPIZ for me for the next 20 miles.

Palmetto Park is 60 miles from the start line in San Marcos. In the nine hours it had taken us to get there, we’d moved up from 157th on the starting grid to 15th place overall. The possibility of a top 15 placing, and the trophy that came with it would be the focus of the rest of our race.

By Palmetto, we’d successfully negotiated the crowd pleasing obstacles of the race, with only a minor spectacle at Cottonseed. The sun was starting to go down and the crowds were starting to thin out.

Erin McGee, one of the most successful safari racers of all time, had told me once that the first 60 miles of the Safari was what everybody saw in the videos. It was exciting. It was daylight. There were crowds, and the camera batteries still had power. The real race happens after that. Pulling away from Palmetto for the 23 miles to Gonzales Dam near the confluence of the Blanco and Guadalupe rivers, those words were playing in my head.

“60 miles of excitement. 200 miles of grind.”

The only physical obstacles ahead of us now were Gonzales Dam, which was probably the ugliest of all the dam portages, and the last six miles across the bay from the river mouth to the finish line in Seadrift. The rest would be flat water, with some occasional current.

With night falling, we switched over to double blades for the first time. Dave set the rate from the front seat and we settled into a steady rhythm. Kate and I were the kayak specialists in the boat and it was a bit of a relief to switch out after a day of chasing Dave’s fast stroke rate on singles.

As we approached Gonzales, darkness was falling and the toll of setting the pace from the front seat was starting to take a toll on Dave so we agreed to swap 1 & 2 after the dam. With a few hundred yards to go, the lights of the dam appeared. High intensity lights casting deep shadows over the trees on the river bank where we would have to begin our portage.

An official on the bank watched silently as our boat nosed up to a protruding branch which marked the start of the portage. A six foot, near vertical mud bank with a couple of roots and a rope hung down for purchase. There was only enough footing at the base of the rope for two of us at a time. Dave and I jumped out and started scrambling up the rope. When we were halfway up, Mike and Kate poked the bow into the air and we pulled it up behind us as we summited the incline.

The race photographers would later post photos of fake rubber snakes and spiders which the checkpoint officials had scattered around the tow path of the portage to amuse themselves as competitors went through. I didn’t see any of them. I doubt I would have cared. I remember thinking I wouldn’t have been surprised to see a serial killer with a chainsaw jump out on the path, because that was about the only thing that wasn’t in our way as we dragged the giant boat through a winding path in the trees.

Scrambling down the bank on the downstream side of the dam, Dave took a tumble and went down the bank and into the water. It was the first time I’d heard him say fuck. I was starting to wonder if he had it in him.

Leaving Gonzales, I jumped into the bow seat so I could set the cadence on double blades for a few hours.

Switching seats was a mixed blessing. I gave me a chance to get into the front seat and settle into a stroke rate that I could keep up for an extended period of time. I generally find it harder to match somebody else’s cadence. The downside was that this was Dave’s seat and everything from the foam padding to the GPS was set up for his preference. Most notably, the GPS was in miles with completely different layout to mine. From my seat, our speed dropped from 12 (kph) to 7(mph) Aaargh!

The other downside was that I no longer had anybody sitting in front of me with the checkpoints conveniently printed on their back. Each of us had a team shirt with the checkpoint names followed by their mile and kilometer distances. If you wanted to know what was next all you had to do was look forward. Unless like me, you were in seat one.

…time and distance passes in a blur…

We switched back to single blades somewhere. We’d been passing boats while we were double blading, but they would start to pass us again as we went back to singles. At one point we heard we had moved up to 13th place or that the team we’d just passed was in 14th.

Through the night, we found ourselves in a duel with a four man canoe full of buff young guys who were keen to tell us how many finishes they had between them in the boat. The duel went on for several hours, with position switching constantly. We would pick different lines in the various currents of the river. They tried to outsprint us a few times, but we’d claw them back as they eased. For a long period we were paddling side by side, mutually pacing, while we chatted between the boats.

At some point, our bow light started failing. It dimmed, it flickered, and then it failed. Fortunately we were pacing the boys so we could use their light to navigate. We stayed with them until the next resupply at some muddy bridge in the dark.

At the resupply, we fiddled with the light, cutting the switch out of the circuit to eliminate a possible failure point. That seemed to work and the light glared back into life. Light working again, we set off into the darkness ahead of the boys who seemed to have burnt a bit of energy in the head to head. It was probably a bit reckless to engage in a duel with so many miles to go. We’d burned some energy and raised some blisters on our hands, but it had also lifted the energy in our boat for a few hours when everybody was struggling with lack of sleep.

Dealing with lack of sleep had been one of our concerns pre-race. Mike and Dave had experienced it before, but there aren’t any races in Australia where you are on the water for longer than 15 or 16 hours unless you’re having a really bad time. The longest we had ever raced was 10 hours until we deliberately started training for 24.

That training started with the 24-hour relay at Burley Griffin in Canberra, where we’d opted to race without teammates in a single boat. We’d both hit the wall at around 18 hours with me getting so cold in the 2-3am period that I simply couldn’t rewarm. We’d been ill-prepared for a temperature drop at night in Canberra, thinking it was summer, and once we were cold, we didn’t have the body temp to warm up again. Lesson learned – Don’t let yourself get cold. Keep your body from entering it’s cool sleep period.

A series of 24 hour training paddles followed on Lake Yarrunga in Kangaroo Valley. Each paddle was progressively more successful as we solved problems with clothing, high energy foods, and finally pharmaceutical measures. In this case Modafinal (Provigil in the US), a prescription medicine that is prescribed for narcolepsy, long haul truckers, shift workers, and pilots to help them stay awake. It is also used by university students as a performance enhancer. We expected that getting a prescription would be difficult, but it wasn’t. Our GP had never heard of it and was curious to hear how it worked.

It definitely worked. On our final training test, we’d been awake all day, and started our paddle at 8pm to the astonishment of the campers in the carpark that we were actually going out into the dark, just to paddle around in circles. We’d started yawning about 11pm and were having microsleeps by midnight. One pill and thirty minutes later… wide awake. Not sleepy. Completely focused. That lasted until about 5am by which time the sun was starting to come up and daylight jump started the rest of our day.

Afterwards, a friend was quick to warn me that there were some potentially nasty side effects from ProVigil. In my case it was a splitting headache as they wore off. Other accounts range from reduced effectiveness to hypervigilance. We packed them in our bags for Texas with the agreement that we would only use them once.

Twenty or thirty minutes after dropping the boys at the resupply point, our bow light started to dim. Then it flickered. Then it failed. Obviously we hadn’t removed the bad component at the resupply.

It was dark on the river, with the barest amount of moonlight. We couldn’t fix the light on the river and couldn’t see far enough into the tree lined river banks to find a safe stopping point. So we moved to the middle of the river and kept going.

By this stage the river was wide enough that we could avoid most of the obstacles in the dark. We bounced off a few logs lying in the water and ran into the odd rocky patch. John Bugge had told us the boat was nearly indestructible as long as you hit everything head on. In the darkness, we were putting that to the test.

As our eyes adjusted to the darkness, and the shapes of the water, it became easier to pick out the logs and ripples on the water, making the journey a lot smoother.

Mike said he’d spotted another boat up ahead of us. We could see them as dark shapes against the white riverbanks in their head lights. They were about half a mile in front of us and kept disappearing in the bends of the river. The odd thing was that they seemed to be getting bigger. Not just bigger because they were getting closer, but really big. 10 feet tall big. Suddenly we realised that the boat we were chasing was actually our own shadows being cast ahead of us by the powerful lights on the boat coming up behind us. The closer they got, the bigger the shadows grew. It was the boys again.

About that time we ran headlong into a log jam we hadn’t seen. We hit it hard enough to knock us all forward on our seats. Luckily, it was also shallow so there wasn’t any risk of being washed under or across the log which would be a real problem in the dark. Even luckier… it had knocked the bow light hard enough to make it work again. After that we continued to have occasional problems with the light, but now we knew they could be solved by simply smacking it very hard with a paddle.

…time and distance passes in a blur…

As darkest night gave way to early dawn it was time to start managing our fatigue. Exhaustion was still many hours away. When we had been fitting out the boat, Mike had crafted a foam pad for seat three that would allow somebody to lie flat enough to get some sleep in the boat. If you looked at the set up, it didn’t look possible, but with your lower back on the pad and your shoulders on the seat, it was workable. You just had to be tired enough.

Dave was the first to go back to the sleeper seat. I don’t think he lasted more than 15 minutes before he was up and paddling again. He was stuck between too uncomfortable and guilty about not paddling.

I decided to go next. As I closed my eyes, I was thinking “How the Hell can I sleep while the boat is rolling and Mike is splashing me?”.

I woke up again as the boat clattered off some shallows. Mike said I’d been down for 30-40 minutes. It might not seem like much, but in the context of 22 hours on the go, it was a lot.

Kate couldn’t sleep because it was getting light and Mike decided that he would try later when we were on easier water. For them, later would never come.

The sun rose over a river which was wide and meandering between tree lined banks. There was some current, moving barely faster on the bends than elsewhere on the river. We spent the morning chasing ripples of faster water from one side of the river to the other.

As the temperature rose, the focus turned to resupply points and managing our hydration. Desperate to avoid debilitating cramping, we were going hard on the electrolytes. Dave had sourced an electrolyte supplement which could be added to water. Reading the list of ingredients, it was basically dilute seawater. Dave swore by it and it seemed to be working. It was great until I remembered what the subtle taste reminded me of… drinking water from a glass that has had milk in it without being rinsed… Bleerk! You get a lot of time to think about little things like the taste of your water when all you’re doing is putting your paddle in the water stroke after stroke. Once I’d got the idea of dilute milk in my head, I found it increasingly harder to drink the additive in water.

This is where the team captains supporting us become even more important. When I said I couldn’t drink any more electrolyte mix, they turned up at the next resupply with Gatorade. When we wanted more ice in the jugs, more ice appeared at the next checkpoint. When the temperature soared they turned up with tubesocks full of ice and tied together which we could drape around our necks while we paddled. The highlight of the day was pulling up at a checkpoint to find segments of watermelon waiting for us. Cold, sweet, watermelon!

We saw the C4 boys a few more times during the day. They’d gain on us while we were single blading and slip behind as we double bladed. Another boat came into view ahead of us in the later part of the day. Brian Jones in his C1 had rocketed out in front of us from the start and we were only just catching up with him after thirty-something hours. Brian was obviously in a bit of strife, paddling slowly and looking like he was struggling with the heat. It was hard to tell if he had gone out too hard and crashed or he was just having a low point in his race.

At this stage we thought we were around 13th and Brian and the boys were somewhere behind us waiting to snatch a top 15 place from us if we faltered.

…time and distance passes in a blur…

The river slowed and the heat increased. Around 200 miles in we reached Victoria and a section of river which is an insane series of bends, leading into other bends. Its as if somebody said build me a river between these two places, and I’m paying by the mile. We’d paddle into a bend which would run almost 270 degrees to the left before turning into another bend which went 270 degrees to the right, and on and on and on.

Mike finally convinced Kate to switch seats so he could get a rest from the steering. He’s been going for 30 something hours and his legs were cramping. The tight bends can’t have been helping.

Kate steering caused some concern with Dave. Our style of racing in Australia is to run the tightest line around corners and keep the distance as short as possible. What you lose by not being in the faster current at the outside of the bend, you make back in distance not paddled. I was happy to have Kate driving on these crazy horseshoes after losing my mind earlier when we would paddle a left bend then cut diagonally across the river to chase a ripple on the opposite side. Now Dave was losing his mind over the way she was cutting through the shallow corners.

We’d just had a conversation about how Mike had logged a GPS track of 268 miles for the 260 mile race a few years earlier and I was happy to see Kate cutting corners.

We convinced Dave that she wasn’t a complete novice (she’s driven boats to three consecutive podium finishes on the 404km Murray Marathon in Australia) and that he should let her do her thing. The water was slow and the river level was high, so there wasn’t any real penalty to being on the inside of the bend because it wasn’t much shallower, or much slower.

We’d been running a couple of miles over the race distances on our GPS track when Kate took the wheel. By the time we reached the next checkpoint we were two miles under the race distance. Mike noted later that our split time for that section was the fastest of the race.

Hallucinations started in the afternoon. Trees became people. Logs became jaguars. There was a four foot monk in a cloak fishing off a rock on the riverbank. A fallen branch across the river became an alligator.

Well not everything was a hallucination. The alligator was real, about eight feet long, and it had friends.

We also had our first encounter with alligator gar. Describing these as some prehistoric nightmare plesiosaur, alligator hybrid doesn’t really do them justice. They are ugly as a sack of hammers and also very large. We’d been warned by veteran paddlers that they had been known to jump at lights and into boats, occasionally injuring paddlers who had opted to wear headlamps in the race. It was one good reason why our light was fixed well forward on the bow of the boat. Night was still many hours away, so it was a bit of a surprise when we hit a gar which had apparently been sunning itself just below the surface of the water.

Did I say they were big? Big enough to lift a 30 foot four man boat about 4 inches higher in the water as it flicked away startled by the unexpected impact. Everybody was wide awake again.

Emerging from the insane switchbacks, our next landmark was 3 o’clock cut, the shortcut into Alligator Lake, which we’d mapped on GPS earlier in the week.

It was dark by the time we reached the cut. We were lucky that Mike knew the area well enough to find it in the darkness. From my seat the entry to the portage looked like just another spot where an alligator had slid down the bank. Jumping out of the boat, we were all exhausted. With Dave’s ankle now well and truly swollen, he could barely lift his share of the boat and it was all Kate, Mike and I could do to get it hauled up the muddy bank and slide it in short dragging stages through the trees to the ditch on the other side.

As we struggled to get the boat floating in the ditch, a re-energised Brian turned up in his C1, sprinting the the trees beside us with a boat that was probably a fifth of the weight and 12 feet shorter.

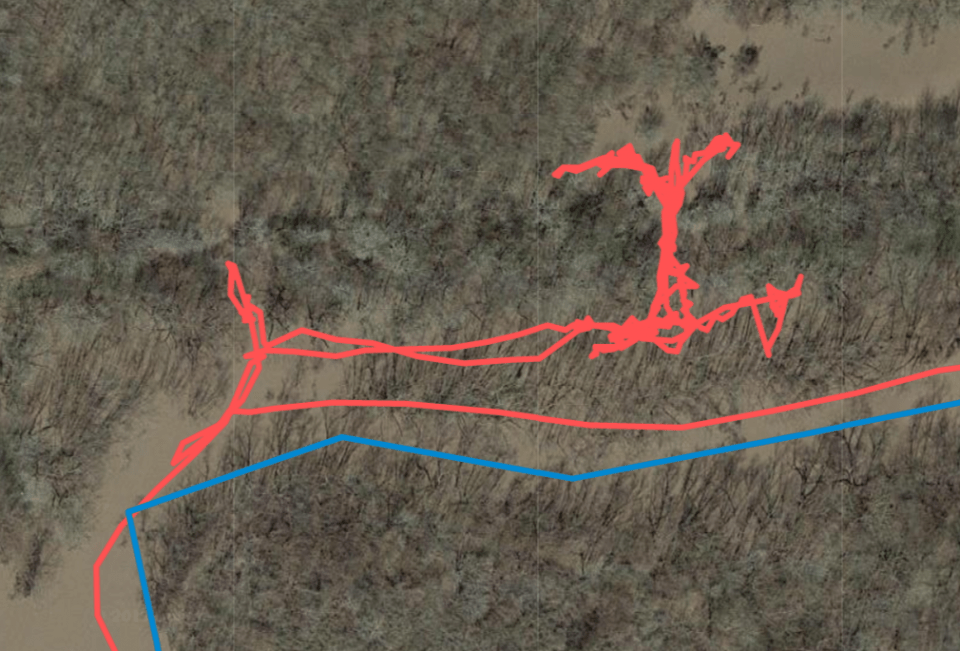

Desperate to keep Brian in sight, we charged madly into the swamp . It was our first big mistake of the race. We’d entered the swamp without reference to the GPS track we’d plotted earlier and when suddenly we lost sight of Brian, we were left wondering where the hell we were.

We’d been following Brian until he disappeared through some bushes and when we turned the boat into what we were sure was the same channel, there was no sign of either Brian, or a way out.

The GPS wasn’t a lot of help with too much cover overhead, the location was questionable and we were stationary so the direction indicator was even more questionable. The GPS track showed our position as about 10 metres from the path that we’d plotted. There just didn’t seem to be any way to get to the track from where we were.

At one stage, Mike was convinced that all we needed to do was push directly through the trees and swamp in a particular direction and eventually we would hit the lake. I didn’t have a good answer to how we got out of the swamp, but the GPS compass was saying Mike was facing North and the lake was due south, so we canned that idea.

I don’t know how we stumbled across the ditch that finally led us out of the swamp and onto the lake. It felt like we had nosed the boat into every possible option before running out of water or clearance and being forced to back it out again.

Finally we were out on the lake and in the clear.

I later discovered that one of our four GPSs did have a magnetic compass. Of course, it was the one that didn’t have the course loaded. Something to remember for next time. A compass bearing would have been really useful.

We plotted our path across Alligator Lake in daylight. We’d had to navigate a tortured path through swamp grass and clumps of vegetation to reach the narrow exit channel hidden amongst the trees on the Southern edge of the lake. We’d expected the rain falling upstate to lift the water level by five feet which would drown out all of the vegetation leaving us with a direct line from the swamp entrance to the lake exit. In anticipation of that high water, I’d drawn the GPS track with a direct path from entrance to exit. Inconveniently, the lake level hadn’t risen five feet and we were on a lake full of vegetation, in the dark, with a flakey light.

Mike drove the lake blind from memory and did a great job of remembering the way through.

The lake was dead calm as we crossed. We were quietly serenaded by the gentle chirp of water creatures living in the clumps of grass. I’d concluded quickly that they weren’t birds, and being Alligator Lake, they were probably baby alligators, thousands of baby alligators. Deep thinking was getting harder but it still managed to conclude that baby alligators come from mummy and daddy alligators. My fatigue addled brain had no interest of pondering how many mummy and daddy alligators it takes to make thousands of babies.

We were quite relieved when we found the exit from the lake and back onto the Guadalupe. We’d lost the best part of an hour in the shortcut. Brian had slipped past us and in all likelihood other boats had also slipped past while we were circling the swamp looking for our way out. We figured our chances of being in the top 15 were long gone. We were back to chasing a finish and a respectable time.

While we paddled to our next resupply and final checkpoint at Saltwater Barrier, we discussed our strategy for crossing the bay to Seadrift. Mike reckoned we were his secret weapon if the bay was rough as Kate and I are both ocean paddlers and were used to paddling in waves. Our plan was to switch seats again, putting Kate in 1, Mike in 2 to balance the front of the boat, Dave in 3, leaving me to steer from seat 4.

We needed to stop at saltwater barrier, rig the spray deck on the boat, do a final resupply and put our life jackets on for the last six miles.

If resupplying six miles from the finish seems a little nuts, it’s not. Paddlers have spent 24 hours variously crossing or walking around the bay on particularly bad years. A capsize on the bay could mean a few hours in the water trying to get back into the boat. Any outside assistance means disqualification, so pack for all eventualities.

There was good news at the barrier, the lightning storm that had been running behind us to the North West wouldn’t reach the bay for several hours and we would have a glassy bay crossing. We decided not to fit the spray skirt. It was large, cumbersome and difficult to fit with its snap fittings, especially when your hands are ground beef from 40 hours of paddling.

We spent some time at the barrier trying to sort out the flakey light on the boat for the final time. We would need the light to navigate our way out onto the bay through Traylor Cut.

My left hand had taken a beating when we’d been dueling with the boys and I had a set of coin sized blisters that were full of fluid. I’d been able to avoid them while we’d been paddling single blade. Double blading across the bay was going to be unworkable unless I dealt with them. It was ugly, but really the only way was to pop them all now and put up with the discomfort for the last 6 miles. Rinsing the worst of the mud off my hands, I shoved the blade of my multi-tool through the sides of the blisters to drain the fluid. I considered some duct tape to cover them, but nothing would stick. We were too dirty and too muddy. It was only six miles.

Normally, racers follow the Guadalupe all the way to the South Guadalupe river and exit into Guadalupe Bay then its a quick run across to the wall of a barge canal, around the end and into the finish line in Seadrift. This year the South Guadalupe river channel was choked with hyacinth making it virtually impassable. The solution was to turn off the main river at an earlier point called Traylor cut which would bring us out a few miles further up the barge canal wall on Mission Lake.

Apart from being a less direct route, there wasn’t any problem with Traylor Cut. Notably though, only Dave had ever taken that route before. The rest of us had no idea what to expect from this route.

We were almost ready to pull away from the boat ramp at the saltwater barrier when a womens C4 team went steaming past us. They must have been able to smell the finish line because they were flying, especially if you consider that we had all been going for more than 40 hours now. With Brian in front of us and now the womens team, we were slipping down the race rankings.

As they past I heard one of their support crew tell them that they were now in 15th place. That had been us! Even after all of our trouble in the swamp, we’d only dropped two places and had still been in the top 15.

I could say that we took off after them with a renewed vigour, but what really happened was less heroic. We turned into the current with me steering the boat for the very first time. Not being familiar with the feel of the huge rudder, I initially thought the rudder was broken, and tried to pull into boat ramp to unjam it. I completely missed the turn, underestimated the current, crashed sideways into a tree, and lost my paddle over the side trying to not be swept under the tree I’d just run us into. Getting to the boat ramp, I discovered that the rudder wasn’t broken, it was just very large and being pushed sideways very hard by the currents running behind us.

The next ten minutes were spent variously chasing down my paddle, which thankfully had reflective tape wrapped around it, and bouncing off various obstacles as I literally did a crash course in steering the beast of a thing. I had a new respect for Mike who had steered it non-stop for over 30 hours.

We were most of the way through Traylor Cut before I got the steering workably dialed in.

On top of the steering issues, hallucinations had kicked in with a vengeance. The circle of light from the boats head light would play across a tree on the riverbank, but it wouldn’t be a tree, it would be a 30ft soccer ball, with all of the details. I swear it said inflate to 40 psi beside the valve.

The area around Saltwater Barrier is part of Hallucination Alley, and the hallucinations were spectacular. We were hours beyond the blink-and-it-goes-away miasmas. Two months later I can still see the Death Star; the front half of an Imperial Walker; a plethora of South American sculptures featuring skulls, death masks, and a couple of fertility gods. I can’t explain how these images emerged from my addled brain, but they were coming through in very clear detail. They appeared to be either carved out of stone, bone, or built from papier-mâché. All bleached white in the harsh light of the boat light.

Rather than being freaked it by the macabre imagery, I was actually enjoying what the fatigue was doing to my brain.

Talking with other paddlers after the race, the skulls and statues theme seems to be quite common. One paddler recounted the hallucinations talking to him, so as much as it was novel to me, I was definitely at the low end of the scale. Maybe the result of the 40 minutes sleep I’d managed at dawn the day before.

If I was seeing this stuff, what were the others seeing?

Exiting Traylor Cut, we emerged onto the west side of Mission Lake and turned to follow the shoreline South to a point where we would cross to the spoil wall that marks the boundary of the barge canal. The barge canal wall would lead us to the edge of San Marcos Bay and from there we would be able to see Seadrift and make our final run.

The barge canal is an out of bounds area for racers. The protective wall has several breaks in it, and as tempting as it might be to slip through and use the walls to shelter from the wind and waves on the bay, transiting the barge canal would earn you a disqualification. The only time you can cross the canal is at the end when you make the cross on the final approach to Seadrift.

We started following the southwest edge of Mission Lake, only to discover that it was shallow and had a number of small bays which just slowed us down. We decided to make the crossing to the barge canal wall and follow that as a guide. That meant we were on the finish line side of the largest expanse of open water if the storm arrived and the bay suddenly turned sour.

The race guide says that it is six miles across the bay. Mike had said that you can see the lights of Seadrift from across the bay and just follow them in to the finish. The detour through Traylor Cut the bay might have nudged it closer to 9 miles. We soon discovered that there’s another set of lights at a dock on the barge canal, and we were coming at Seadrift from a very different direction to Dave and Mike’s usual approach.

We were all exhausted and struggling to maintain a consistent stroke rate behind Kate who seemed to have revved up for the final few miles. Sitting in the back seat, I could see Kate running at a medium-high cadence, Mike struggling to keep up in two, Dave trying frantically to follow Mike but stopping to reset every 5-6 strokes. I tried to ignore the two guys in the middle and follow Kate, but the crazy mexican wave of timing was melting my brain and everytime I tried to sync up, I’d be on the wrong side in 5 strokes.

The net effect was that we were now on an unfamiliar course, making less progress than we’d expect, with conflicting landmarks in front of us. What happened next was inevitable.

It started when I drifted the boat through a break in the canal wall. We’d slipped about 50 metres into the canal before I spotted the end of the next section of wall on the other side of the break. The officials at the race briefing had said it was OK to enter the canal accidentally, as long as you exited straight back out. I turned hard to get back out into the bay.

That set off a chain of events which ended up in a near mutiny. Dave was convinced that we had either missed the exit to the barge canal and were on our way to Cuba, or that we were in the barge canal and were now disqualified. Meanwhile, I was looking at the map display on my GPS and it was telling me I was exactly where I expected to be. Mike was also questioning our position based on unfamiliar lights in the distance. Dave and Mike wanted to turn around and backtrack to Traylor Cut. I was saying that we just needed to follow the canal wall a little further, but each outcrop on the wall which I hoped was the end of the wall, just exposed another section of wall off into the distance.

We would paddle a few hundred metres, stop, argue about our position, paddle some more and repeat.

At one stage a four man canoe which we guessed would be the boys, crossed the channel ahead of. I argued that that they were heading the same way, Dave was convinced that they were just more lost than we were.

Just as it was coming to a head, we spotted a boat ramp on the shoreline that we could pull into. As we all jumped out, Mike retrieved his phone from the rear hatch and pulled up Google Maps to check out position and show me how far off course I was. After a few minutes standing around in the water while Mike maneuvered to get a signal we got our answer.

“Seadrift is 118 yards that way.”

The shock broke the tension. The different approach angle, fatigue, pain killers, and probably the ProVigil had conspired to befuddle us in the last few miles. We were so close that the officials could probably see us, wondering what the hell we were doing.

With no more doubts about which way we were headed, all we had to do was get back in the boat and paddle along the shore to the finish line.

We crossed the finish line in Seadrift at 5:30am after 44 hours and 30 minutes. We had dropped to 17th place from 15th at the saltwater barrier, which was down to other teams having a better finish than we did. The boats in front of us had earned their position. Boats would continue to arrive in Seadrift for another 56 hours until the race cutoff.

We stumbled around the finish line while Dick and Tom did their best to point out showers, chairs, toilets and other evidence of civilisation. The organisers had arranged access to showers and bathrooms with a motel nearby. After 44 hours on the move, we had porcelain again.

The next 48 hours were spent returning to normality. Dave had booked a double room in a local hotel where we could get some sleep for a few hours. Strangely, we couldn’t sleep easily, so we got freshened up and headed out to grab some breakfast.

The rest of the day was spent wandering around Seadrift. We’d occasionally bump into Mike, Dave, Dick and Tom. everybody had sort of withdrawn to their own spaces, which is understandable given the compression of the past ten days.

Seadrift is a small town. I don’t know what happens there for the 360 days of the year when the Safari isn’t in town, but I suspect they spend their time breeding prize winning mosquitoes. There were a few good restaurants, a store which had decent stocks of the things we needed, bandaids, antiseptic, and mosquito repellent – industrial strength mosquito repellent. The mosquitoes were world class.

We wandered between places to eat and the finish line where paddlers were still arriving thick and fast. We must have arrived during a lull, because there were very few people at the finish when we crossed the line. Now there were about 100 people scattered across the chairs and tables set out under the finish line marquees. Shattered souls wandering around trying to make sense of their achievement. Small groups celebrating their successes. Talking quietly or laughing uncontrollably. The conversations paused for a cheer as each new arrival appeared on the bay.

They were still arriving during the finishing banquet at noon on Sunday. The officials announced that there were still a half dozen teams on the water with a chance of finishing before the cutoff.

The six man SUP was still coming. They’d had a collision with a log upriver and one of their paddlers had gashed their leg badly. Luckily, one of their team captains was an EMT who had stitched them up on the river bank. They were back in the race and expected to finish before the 100 hour cutoff.

We were under the finish line marquees for the banquet when the storm finally arrived, giving us a taste of what the bay can throw at you when it chooses to. Wind drove waves and whipped water across the bay almost horizontally. Mixed emotions blew across the crowd, thanking luck, preparation, or the river gods that they weren’t still out there, and a moment of sympathy for those who were.

There were a record number of boats entered in the Safari in 2019, and a record number finished. Only 32 of the 176 boats on the start line had dropped out, failed to beat the cut offs or been disqualified. In other years the attrition rate can be 50-60%.

Kate and I had no reference point for how difficult 2019 was, being our first year. Experienced paddlers tell us that the high water levels and lack of major log jams worked in favour of the racers. On the flip side, the heat certainly took a toll on many paddlers.

We’d been pretty well prepared for the challenges we knew about, and the struggles had been with the unexpected.

The dams and portages had been fun, probably because we’d expected them to be tougher. By the time we saw alligators, we were too tired to care. There were undoubtedly snakes in the log jams and on the river banks, but I don’t remember seeing any. By the time I stepped in a fire ant nest, I was covered in so much mud that I didn’t feel them. The only poison ivy we saw was while we were scouting pre-race. The heat was very much like home, much like the river for the last 200 miles.

Despite our momentary lapse of reason on the bay, we paddled the boat to Seadrift, collected our finishers patch, and earned the t-shirt. We are all still friends.

We owe a huge debt of gratitude to our team captains Dick and Tom who were awake for almost as long as we were driving endlessly across the obscure backroads of Southern Texas, clambering down muddy river banks, and baking in the sun to keep us supplied with iced fluids, food packs, and most of all endless encouragement.

Of all the races we’ve finished over the years, the Safari stands alone as the race you cannot do without a support team. The rules don’t allow you to race without a crew. They are responsible for the first line of paddler safety, logging teams progress through the various checkpoints, monitoring team health, and possibly being the humans you will see over the extent of the Guadalupe. For the last 200 miles we barely saw other paddlers, let alone people on the bank who could provide assistance in an emergency.

Thank you Dick. Thank you Tom.

We set out to complete two bucket list challenges in 2019 – The Toughest, and The Longest canoe races in the world. Was the Safari the toughest? Standing under the finish line marker at Seadrift and looking back over 260miles of river in 44hours and 30 minutes, it was tough. Would the 444mile Yukon River Quest be tougher, we would find out soon enough.

Would we do it again? With some races, you get to the finish line and cross them off your list, their value is in having finished them. Some races, it takes some time to wash the dirt off and see the sparkling moments of joy that you collected along the way. For me the Safari was in another class. I am hooked. The river, the event, and most of all the people have captured my heart. Before we left Seadrift for the next leg of our trip, I knew we would be coming back one day. We’ve already planned for a different boat and some different tactics.

It won’t be 2020, but I’m pretty sure we are coming back.

If you want the abridged version of this yarn, and it’s a bit late now – check out Mark Sundins Expedition Kayaks Podcast where he interviews Kate and me about this adventure

Help encourage more posts by buying Steve a coffee…

Choose a small medium or large coffee (Stripe takes 10% and 1% goes to carbon reduction)

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Donate