This is the story of Steve & Kate Dawson, Team 11 – Dawsons to Dawson, in our first attempt at the 700km Yukon River Quest in 2019. We finished 25th overall (2nd Mixed Kayak) in 55 hours 10 minutes.

Whitehorse

The Yukon 1000 starts with a 400m run from a city park in Whitehorse to the lineup of boats waiting on the riverbank. Naturally some people set off a run, while others start out walking. It’s a 700km race and line honors are unlikely to be decided by to 30 second advantage gained in the footrace at the start. But you get caught up in the moment, and start to run, dragged along by the front of the pack.

Our boat was waiting for us on a gravel spit near the front of the starting grid with Erin, our local support person, waiting to help us with a big shove into the water. Grid positions are assigned according to the order of entries and we were number eleven on the grid.

Anticipating the crowd would run, I’d made a point of checking the depth of the water between the main bank and the gravel spit, so I knew I could make a bee line for the boat and not disappear into a deep hole.

Our boat was fitted with marathon style spray decks with centreline zipper entries, so we could access food and gear in the cockpit without having to struggle with the spray decks. The decks were already fitted to the boat, so all we had to do was slip in, zip up, and shove off.

With a big shove from Erin, we were on our way to Dawson.

The Yukon river at Whitehorse is about 200metres wide and had a good current flowing over a bed of gravel. The banks alternate between tall gravel banks on the outside of bends, cut close to vertical by river erosion, and shallow gravel beaches on the inside of the bend.

For a kayaker, shallow water is slow, deep water is fast. You try to stay in the main flow as much as possible unless you can cut the corner by so much that it overrides the slower water. You look for the shortest path through water that isn’t too shallow. It’s always being reviewed, moment to moment, as you take your cues from the riverbanks going past, the speed reading on the GPS, and your position relative to other boats.

Pacing against other boats is always a bit problematic as you never really know how hard they are working or how naturally fast they might be. That was even more true for the first 30km of the Yukon, where we had no familiar crews around us and everybody was a little hyped up by the excitement.

As we passed Takhini bridge 20km and nearly two hours downriver, we still hadn’t really settled into a pace. We had been there a few days earlier on a test paddle with the outfitter we’d rented our boat from.

Already the boats were starting to stretch out on the water. There were about twelve boats in front of us and none of them were kayaks. Two German men in a K2 were nipping at our heels and there were a few single kayaks still visible in the distance behind us.

Logically, you know that with 120 boats on 700km of river over 90 hours, there would be lots of space between crews. I’d looked at the race tracker date from 2018 and knew that there was more that 10km between the leading boats by the time they reached the finish line.

But damn it got lonely fast out on the Yukon.

Policemans Point

Policeman’s Point is 37km downriver and marks the start of Lake Laberge, where the river stops flowing and crews can expect to slog it out unassisted by current for 51km. That’s 5 to 6 hours for the average tandem kayak. More for a solo.

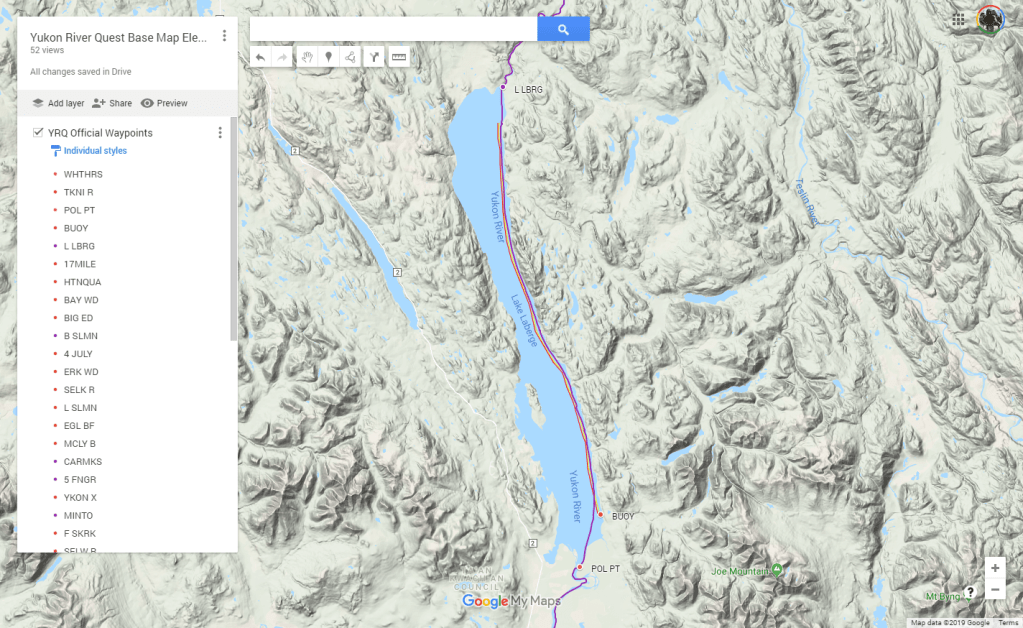

Lake Laberge

Although the lake was glassy as we entered, it features prominently in the race briefings for it’s localised weather and exposure to the winds. Boats are required to remain within 200m of the Eastern shoreline as a safety measure. I’d loaded our GPS with a no-go line which marked the limit of the 200m corridor. The lake shore curves through a number of large bays so following the shoreline religiously will add some unnecessary distance. Our plan was to make as straight a line as possible to the northern exit at Lower Laberge.

An hour into the lake, the wind started to pick up and the first signs of trouble started to arrive. It wasn’t long before we were pushing into 1-2ft waves from our 10 o’clock. We’ve paddled a lot of open water so the waves themselves weren’t bothering us, but being whipped up by a fresh wind, they were close together and choppy which our boat wasn’t handling well. The bow would plunge into the oncoming wave and Kate was getting a chestful of wave every time.

The rules also require kayak crews to wear spraydecks from the startline to the end of the lake for exactly this reason. Canoes have the option of partial covers, or full decks.

Despite her spraydeck, Kate was going so deep through the wave that the water was pouring into the boat through the waist tube, which was riding low and loose so it wouldn’t chafe. Slowly but surely we were taking on water. With four more hours on the lake that could be a serious problem.

Another problem became apparent when we stopped momentarily to put our jackets on for some relief from the wind. Kate had no trouble getting hers, but mine was in a dry bag that I’d shoved in past the footrests of my cockpit. There was no way I could contort myself enough to reach it while we were out on the water. I hadn’t thought about how I was going to reach it when we were out on the lake. On the river pulling over was an easy matter because the banks were nearby.

Now it was too far forward to reach and the improvised footbar was stopping me hooking it with my foot. We’d need to land on the shore for me to reach it. Just ahead of us, a point of the shoreline poked out from the right close to where our direct line would naturally take us. Sadly, “Just ahead” was about 10km across the distorted view of open water. I was going to be wind chilled and taking water through my spray deck for the next hour without my jacket.

That pause to put our jackets on should also have been an opportunity to bail some excess water out of the boat, but that didn’t go well either.

The mandatory equipment list required a bailer or a pump. Concerned about the amount of gear we were carrying, and not expecting to need a bailer, I’d opted for a large yoghurt container as our bailer. In deference to the race rules, I’d written BAILER in black sharpie on a bit of tape and stuck it on the side to make it compliant. The official who checked our gear pre-race had been a bit sceptical, but he wasn’t a paddler, so he’d let it go.

Now I was discovering that the bailing efficiency of a 1 litre yoghurt container is less than the leaking efficiency of a spray deck in waves without a jacket over the top. We had about 30 litres of water sloshing around the boat by the time we reached a suitable beach. Not enough to make the boat difficult to handle, but certainly not a dry ride.

There’s always water in a boat when you’re paddling distance, the idea of a dry boat is a fiction unless you’re prepared to swelter in a dry suit.

Other boats around us were having bigger problems. Off to our right there was a four man canoe with the paddler in seat three furiously throwing gallons of water overboard with a large tupperware container. The paddler in seat two was bracing furiously and the stern paddler was prying the tail around to keep them head on to the waves and not capsize. That left only one paddler in the bow trying to pull the whole four man boat forward. They were going nowhere fast and where they were was a bad place to be. They were going to be bailing for a long time unless they could get some more strokes going forward.

Further along the lake, we passed a six man canoe on the shore emptying out after a capsize.

As we approached the shoreline, a safety boat racing up and down the course around us. They seemed to be checking on teams. The safety brief had covered Lake Laberge in some detail. Paddlers were advised to stay within their limits and pull over to the shore and wait out any squall conditions rather than get into trouble early in the race. If things got really bad, a light aircraft would fly over the course waggling it’s wings as a signal that racers should pull over until the course is clear. The briefing wasn’t entirely clear on whether pulling over was mandatory in that case.

In our double sea kayak, we were still having a relatively good time, despite the head winds. Controlling the boat wasn’t difficult and sea kayaks are designed for these sorts of conditions. In a canoe, rocking over the wave peaks like a see-saw, these conditions would be miserable.

The safety boat reached us as we were approaching the shoreline. The crew yelled something we couldn’t hear over the sound of the wind.

They tried again. “Are you 11?”

“Yes”

“Are you in trouble?”

“No, we’re fine”

“Why are you transmitting an SOS?”

“Huh?”

“Your SPOT tracker is sending an SOS. We’ve been sent out to check on you”

Our SPOT tracker was attached to the stern of the boat, well out of reach. We couldn’t check until we reached the shore. We said we’d check it and asked the safety crew to let race control know we were OK. They told us that we’d triggered a full blown rescue activation and the race officials had been contacted by RCMP search and rescue coordinators to check our status. They’d been able to see we were still moving, so it’s hadn’t escalated to a full blown rescue yet.

The importance of coordination between the race organisers and local support organisations became apparent at that point. Without knowing there was a race in progress, the activation would have triggered a search party to come and find us. As it was, we knew that our kids back in Australia would have been contacted by SPOT to see if it was an accidental activation (something like 60% of activations are accidental).

On shore, we found that the SOS light on the SPOT was indeed flashing red and calling for assistance. Assuming it had been bumped by something in the waves, even though there’s a rubber safety cover over the button, I reset the device and went back to emptying the boat and digging my jacket out from the depths of the cockpit.

Back on the water, slightly colder for the stop, but now protected from the wind, we returned to the business of getting down the lake. Our course put us on a slight angle to the waves coming at us from our left forward quarter. It made for a bouncy, wet ride.

At the end of the lake, we saw the river exit. The lake shallowed as we approached the point where the river spilled out over it’s lowest point. Grinding through the shallows, we started to feel the current beginning to pick up and accelerate us towards the river.

Lower Laberge

The Lower Laberge check point seemed to flash past after the slow grind down the lake. It was great to be back on the river again. With Laberge behind us, we’d have a current pushing us all the way to the finish line at Dawson.

Forests of pine trees slid past as we paddled. It was hard not to be reminded of Joanne Hamilton-Vales summary of her Yukon experience. She’d vowed to never have a Xmas tree in her house again after seeing so many f***** Xmas trees on the Yukon.

We passed a few campsites where canoes had been pulled up on the shore and tents were set up nearby. This was the fringe of civilisation where people with wilderness in their souls would venture for a break. The campsites would be sporadic between Laberge and Carmacks where budding adventurers could get off the river after a few days without committing to the further stops at Minto or Dawson. Sightings of humans would be far less frequent after that.

Just as twilight was settling over the river, we spotted a moose and calf. This was the first encounter with what race officials refer to as Charismatic Mega Fauna, the others being bears of the Grizzly or Black variety. We only had a few moments to watch the two large creatures drinking at the waters edge, but it was a nice moment of distraction. We wouldn’t see any more moose, or bears for the rest of the race. The best we’d manage would be a few furtive glimpses of beavers as the dived off riverbanks into the water as we passed.

Twilight brought a slight temperature drop and a light swarm of small moths which seemed to fly exclusively at mouth height above the river surface.

The river opened out, braiding it’s way along a wide valley. Each braid was a decision to be made and an opportunity for a mistake which would leave us banging the kayaks rudder across the rocks on the riverbed until we found deeper water. In one of these shallow bends we decided to stop and change clothes for the cooler run through until morning. Warm dry clothes are always a bit of a morale booster.

As I was shoving the wet clothes in the back hatch, I noticed that our SPOT tracker was flashing a red SOS again. I reset it and moved it to a new location just in front of my cockpit so I could watch it for the rest of the race.

Over the next 8 hours, our SPOT would spontaneously activate itself 3 more times. Each time, I’d reset it and send an OK message to ward off the possibility of a rescue helicopter appearing over the horizon in search of us. After a reset, it would erratically transmit our tracking position normally for a time and then switch to SOS. It went 2 hours one time and 15 minutes on the next cycle.

We were conscious that if the SOS signal had been transmitted successfully, our youngest daughter Bree, who was our emergency contact back in Sydney would have been woken up with a call to check whether it was a false alarm. We had a parental debate about whether Bree would be concerned that we were sending an SOS or unconcerned because she knew we were probably OK.

As it turned out, she got two calls from the SPOT rescue centre in Texas. The first time they activated a search and rescue response. The second time, they told her that it was probably just a faulty unit and she shouldn’t worry too much about it.

After the fifth activation, we decided to turn off the unit. That meant we would be invisible to the race organisers who were following our progress on the SPOT tracker, but we wouldn’t be raising alarms with search and rescue who might eventually decide to dedicate some resources to coming to look for us. Disconnected from the outside world, we could only guess at how people would interpret our signalling.

I transmitted one last positive OK signal, waited for it to transmit and then powered the SPOT off for the last time. We’d deal with it when we got to Carmacks.

Night on the river was bizarrely short. The sun dipped below the horizon about half an hour after midnight washing the colours from the landscape. The race rules require you to carry a light in the boat and use it during hours of darkness. We were a bit fuzzy about when this darkness would actually occur, but Kate donned her headlamp and made an effort to comply with the rules. As powerful as her headlamp was, it had no real impact on the gloom around us.

We paddled in the halflight until the first rays of sunlight peeked over the horizon again at 3am. We were back in daylight by 3:30.

Morning light bought a fresh chill to the river. With the sun low on the horizon, the river was constantly in shade and there were precious few moments where we would emerge onto river flats where the hills were low enough for the suns rays to warm us.

We’d been paddling alone for most of the night. If anybody had been close, we would have seen the lights on their boats, but nothing.

Some time around 8am we rounded a bend in the river and spotted a solo canoe paddler coming up behind us. He tapping his canoe along at a high cadence, obviously experienced and capable, not just because he was reeling us in however slowly.

It took several hours for him to transition from a distant speck behind us, to a neck and neck duel beside us, and then finally vanish around a bend in front of us just before Carmacks.

It was a bit demoralising for a K2 to be outpaced by a C1. We’re not slouches at this paddling game, but we were getting overtaken by boats that we would generally consider to be slower. Over the next 400km, it would become apparent that we’d fared far better than most on the stormy waters of Laberge and put a healthy buffer between us and some boats who would be faster on flat water, but now well seasoned distance racers were now chasing us down relentlessly.

The arcane YRQ race rules with regard to boat dimensions are designed to ensure that paddler safety is not compromised by boats which are too narrow. Simplified, the rules say, the longer the boat, the wider its beam (width) must be.

Basic hull dynamics dictate that a longer boat is faster than a shorter boat and a wider boat is slower than a narrow boat. Despite the weight of an extra paddler, a long skinny K2 will be faster than a short skinny K1 of the same width.

Because of the YRQ has a minimum width rule, our K2 needed to be 60cm wide compared to 50cm for a K1. Width is drag and drag is bad, so we were getting slowly reeled in by the K1s.

The four man canoes and Voyaguer canoes with crews of 8-10 were also reeling us in because they don’t have to stop for anything. While one paddler eats, the rest can keep paddling. Later in the race, we’d be passed by a womens C4 which were passing us while they were passing their pee bottle around, laughing about who was ready to go next.

Carmacks

We arrived in Carmacks after 23 hours on the go.

Following the advice from the race briefing (yes we were paying attention) we took the longer path in to the checkpoint passing to the right of the island on the approach. We’d been warned that going to the left of the island would require a dash across the current to the dock on the right hand side and bad things would happen if you failed to make the cross before being swept downstream. In hindsight, the current wasn’t that strong and we should have taken the shorter route. The advice wasn’t bad, but probably applies to boats further back in the field.

Tossing the bow line to the volunteer on the dock, we pulled up alongside the pontoon and climbed out as the volunteers steadied the boat for us. All very smooth. While two volunteers took our boat past the dock and up the bank the the staging area, another pair offered to help us walk up the bank. We both waved them off, which took some convincing. We both wanted move under our own steam and get some blood flowing back into our lower extremities after so long seated in the boat.

Erin was waiting on the dock with her two daughters in a whirlwind of support. They had a bag of dry clothes for us, and the breakfast we’d pre-ordered was being cooked on the grill. They’ve been calculating our arrival time, slightly disadvantaged by us turning off our SPOT tracker.

Carmacks is an RV park with a fast food restaurant, small shop, cabins and toilet facilities. Our visit would be limited to two small corridors – from the shore to the boat staging areas, then another from there to the tent Erin had erected for us in the sleeping area, via the portaloos.

It was warm at Carmacks. We’d arrived just before noon and the sun was high in the sky above us. We quickly switched our wet paddling gear for shorts and t-shirts. Our plan was to dry out as much wrinkled skin as possible while we were stopped.

Erin delivered the breakfast burger and hot chocolate we’d pre-ordered on registration day. there would be a second course ready just before we left in 7 hours.

I asked Erin if there was any way we could get a replacement SPOT from the organisers. They’d said something in the pre-race about having some spare units.

Dried and fed, Erin quietly led us through the tent area to our tent. She’d outdone herself. We had an air mattress with sheets and pillows. It was an almost religious experience to stretch out on a comfortable mattress after 23 hours on the go. I slept face down with my arms extended above my head to stretch my shoulder muscles as much as I could.

I was asleep in moments. Kate wasn’t. the noises, the heat and the time of day making it hard to find sleep.

The plan was to arrive, be in bed in 60 minutes and then wake 60 minutes before our departure time. That would give us five hours sleep.

About 90 minutes before departure, we were both awake. The quiet buzz around the camp and the excitement of the race was too front of mind to allow sleep.

We climbed out of the tent and went to check our gear. If we couldn’t sleep, we could at least check our gear and make some adjustments. I needed to fix my foot rest after it had flipped over while I was getting my jacket out. Two minutes with some Duck Tape solved that problem (Not a mistake, you can actually buy Duck brand duct tape in Canada).

We’d expected to change into a second set of dry warm clothes at Carmacks and had left a set with Erin. She’d spent the intervening 5 hours drying out our clothes from the first leg, so it made sense to stick with those for the rest of the race. They would be a bit fresh by Dawson, but they had proved to be comfortable and effective in the cold. We had no rubs and chafes, so why mess with something that’s working. We ditched a spare set of dry paddling gear we would have used from the end of leg 2 at Coffee Creek. A small weight saving win.

Erin had been busy, as well as dealing with our clothes, she’d spoken to the organisers about our SPOT problem. They didn’t have any spares, so they’d changed the race tracker to use Erin’s Garmin InReach beacon instead. I think everybody was happy that we wouldn’t be sending SOS messages for the rest of the race.

Rested, fed, and greased up – we were liberally smeared with nappy rash cream to protect our nether regions – we were back in the boat and off again. 7 hours to the minute after we’d arrived.

Five Finger Rapid

If the challenge of the first leg had been lake Laberge, on the second leg it’s the rapids. Two hours beyond Carmacks, you have to navigate Five Finger Rapids, and then shortly afterwards a second set at Rink Rapids.

If you listen to all of the advice about Five Fingers from previous Questers, you’ll be imagining a mile long rapid with 12 foot waves (actual quote) that are pushing you away from the safe path on the right to a sucking vortex of whirlpools on the left.

While I’ll acknowledge 2019 was a fairly high water year and some features may have been washed out, I struggled to see anything over two feet and it hardly warranted deviating from the fastest line in the middle of the river.

Maybe with less flow, rocks start to emerge and disturb the surface. Maybe the flow speed change on the drop causes pressure waves to appear at higher flows. We didn’t see it.

Lake Laberge was worse.

Beyond the rapids, the river starts to become braided, meandering around sand bars and islands within a wide river valley. This was where we would put our secret weapon to the test.

In most distance races, we use a GPS loaded with a plotted path showing us the shortest path through bends and turns of the river. It appears as a little pink line on the map, and following it is a simple matter of putting the boat on the pink line and paddling.

For the YRQ, there’s a distinct shortage of available GPS tracks. The race requires people to carry maps and many people apparently use them. Our map book was sealed in a plastic bag in the back compartment of the boat. We’d only be using it if both of our GPSs failed. very unlikley.

While most paddlers seemed to carry GPSs, my experience is that most people don’t know how to use them well enough to extract a track and publish it. Those that can, may want to keep their secrets to themselves. Finding a GPS route for the YRQ was nearly impossible. Finding one from a fast team? Forget it.

In the long months of preparation for the YRQ, I’d been working on a hobby project to build a route for the event.

The simple option is to use Google maps and satellite imagery to plot a course down the river. It’s a bit of a mission plotting a course over 700km of twisting river when the curves are really built up from many short straight lines. Every turn of the river is a half dozen or more points that need to be plotted. It can be done, but it will take you half a day to do it.

There’s two flaws when you try that for the YRQ course. Firstly the river changes course a little each year with the flood from winter thawing ice, so the satellite imagery and topological maps might be showing you a branch of the river that doesn’t exist any more. Secondly, it’s not possible to determine which channel is fastest from an aerial photograph. Sure, you can fall back on the traditional wisdom that rivers runs faster on the outside of bends. That’s true for all rivers and works well when the river is a few hundred yards wide, but with the Yukon being more than a mile wide in places, the inside can be half the distance while the outside is only running a 5% faster. Crossing from side to side, chasing the faster water can also mean you’re covering a lot of extra distance for marginal gain.

Solving those two problems required first hand knowledge of the river, so it was clear to me that teams who had paddled the river before had an advantage over first time teams like us. It also meant that you don’t necesarily want to trust a GPS track from somebody just because they’ve finished the race before. Finishing didn’t mean they’d made all the best decisions.

I had managed to find two previous tracks. One was alegedly from Tom Simmat, and the other was from Tony Hystek. Tony had given me his, but suggested following one of the experienced crews as a primary source of direction. When I’d examined his course, I’d noted a spot where he’d been way off the main flow of the river, which didn’t make sense until I looked at the playback from the Yukon race tracker and saw that another boat had taken the same route just a couple of minutes ahead of him. Tony had obviously followed another boat into the slower water simply because they were in front of him.

So even if you could find tracks, they would be peppered with occasional bad decisions and mistakes. Looking at one of the tracks from the K2 winners, they deviated into a side flow in one section which I’d speculate was a stop for a few moments in the bushes. While it would be great to follow the fastest teams, we didn’t need to poo in the same bush too.

Building a better map was going to take some more work and a bit of a new approach.

The answer for me lay in the the YRQ race tracker data. Every team carries a SPOT tracker in the race which sends it’s location back to the race tracker which your friends and family can view on-line. They only transmit every 5-15 minutes depending on their settings and like our useless bloody SPOT, many teams will have their trackers fail or go offline for stretches of the race.

What you can see in the tracker is minute by minute playback of the locations of each boat – imaging them as a series of footprints in the sand. The checkins are up to three kilometers apart, so you can’t just take the fastest boat and draw lines between their checkins. Your track would be mostly over dry ground on the twists and bends of the river.

The dark magic was putting all of the datapoints together on a single map and then weighting the positions of the fastest teams in the channels to determine which course was the fastest. With a hundred boats recording 20,000 points over the race, when you put all those footprints together, there is effectively a beaten trail from Whitehorse from Dawson. When you look at a split in the river, you can see three boats went one way and one went the other. You start with three votes for left and one vote for right, but then weight the votes according to where the teams finished. If the winners went right, the other three were probably wrong.

It wasn’t a small task to extract the data and manipulate it into a format where I could use it to draw a 700km route from Whitehorse to Dawson, but effectively it put the best navigators of the YRQ into our GPS. That was an advantage worth the trouble.

more details on the process can be found in this post

We were about an hour past Rink Rapids when we came to our first significant shortcut. The main river course was a long bend beneath tall cliffs and we could see it extend for miles into the distance. On our left there was a maze of shallow braids amongst trees that appeared to filter into nothing.

We’d come through the rapids with a solo paddler from Alaska who had left Carmacks at the same time as us. Our progress had been pretty even and we’d chatted as we paddled. Just before the shortcut, he’d put in a burst of speed and pulled away from us for a discrete comfort break in the main flow.

Following the magic pink line on our GPS was a leap of faith given the terrain in front of us. There was clearly more water going to the right and no obvious path through the maze of anabranches on our left. This would be the first significant test of the GPS track. If the river had changed, we could be spending the next hour walking back out of a shallow braid. The only hint of security was that the tress on the low gravel islands were at least five or six years old so the river course was probably stable. Probably…

The channel was narrow but well defined as it swung left, then right and opened out to a wide apron of gravel bars heading back to the main channel.

We expected to see our Alaskan pursuer emerge from the trees on the main channel at any moment. The braided shortcut had been shallow and we had likely been travelling slower than he had on the deep water of the main flow.

But there was no sign of him. When we spoke to him again after the race, he said it was like we’d teleported to a location ahead of him on the river. He’s seen us pop out of the side branch ahead and estimated that we’d jumped about 15 minutes ahead in that one shortcut.

The GPS track had proved it’s worth as it would again several times during the remainder of the race.

Approaching the second major shortcut several hours later, we’d just overtaken a C2 as we made the turn. It had been a hard hour of chasing to reel them in and I was hoping we’d be able to use the shortcut to create a gap between us. It’s harder to chase down a boat that you can’t see. You never know whether they are just around the bend or miles ahead. If you can see them, it’s easier to adjust your pace to close the distance.

They seemed to be committed to the main channel on the right as we made a break for a narrow break in the trees on the left, but they guessed what we were up to and hooked ninety degrees left to follow us into the cut. We’d made a tactical error by allowing somebody else to benefit from our course advantage. Something to avoid in the future.

Avoiding it proved to be more difficult than we’d hope though. It’s difficult to manipulate your position relative to other teams when everybody is paddling at a similar pace on a wide open expanse of river. It was hard to get past another team and be out of sight before a shortcut opportunity emerged ahead.

Going into our third major shortcut, we had a quartet of canoe teams just behind us and there was no hope of disguising our intention. They all turned in behind us and followed us into the braids.

Disappointed that we’d squandered an opportunity to create some space, we tried a different tactic. We stopped.

We stopped in a large ponded area with a dozen different exit routes. We could clearly see from the map that our exit route would take us through one of the dozen exits, but looking at the landscape in front of us, that path was far from obvious. The canoes slowed as they approached probably hoping that we would be making a quick stop and move off again to show them the way out of this mess they’d followed us into. No chance of that. We started rummaging around in our cockpits for some food and water, making it clear that we weren’t moving off any time soon.

We watched the canoes scatter across the delta of sandbars as each team placed their bets on a different route out of the braided delta. None of them selecting the less obvious route that we had marked on our route. As soon as the other boats were committed to their paths, we lined up for our own exit and turned up the gas.

Our route had been shallow in places, but the water was moving consistently enough for us to exit back to the main channel a few hundred metres ahead of the nearest canoe. Across the river flats, we could see a couple of the canoes moving slowly as they ran out of water in shallow braids that possibly filtered out to nothing,

Again, we’d had an advantage which we’d unwillingly shared with other teams.

Our tactics were better for the next two shortcuts. We managed our pace to ensure we were well clear of anybody who might follow us into the cut. Mostly that meant a tactical toilet break or pause for fuel. It helped that the distances between teams were increasing as the race progressed.

Minto

Point of no return…

There are thirty five landmarks called out by the race organisers for 700 kilometers of river. They include six checkpoints including the finish at Dawson, and eight monitoring points make up the thirty five. Of those, there are only a handful that are actually meaningful other than to give you something to break the monotony – Whitehorse, Laberge, Carmacks, Five Finger, Minto, Coffee Creek and Dawson.

Minto, a hundred km past Carmacks makes the list because the non-descript gravel bank with a boat ramp is the last road access until Dawson.

The organisers labour the point about the road access during the safety briefing. It’s the last road access for 300km. The last point where you can pull out of the race and get back to civilisation without being rescued.

The rescue process is also explained. You push the SOS button on your SPOT and then pitch your tent in a spot visible from the water. You hang the orange garbage bag supplied by the organisers over a tree on the river bank to mark your location, and then you wait.

Some time in the next 24 hours, depending on what’s going on elsewhere, somebody will come and get you. Just you. Not your boat or your gear. You’ll lose your $500 rescue bond for each paddler and you’ll still have to arrange separately to have your equipment recovered.

And, by the way, they’ll only evacuate you to the nearest road, so you can hitchhike back to Whitehorse.

A full recovery of two paddlers and gear will probably cost you $3000 by the time you get your rental boat back to it’s owners.

Paddling past Minto, you’re stepping off a cliff. If you’re not feeling good, you should pull over at Minto and have a good hard think before committing to the last 300km of the river to Dawson.

When we reached Minto, there were a couple of RV’s and a minivan with a boat trailer. Were they waiting to check on the progress of their crews, or there to offer a ride home for crews who couldn’t face the last 300?

We were feeling OK. We figured we were somewhere in the top twenty teams and probably the third K2. The Kiwis, Ian and Wendy, had blasted past us before Carmacks and two young German guys had been edging away from us since about the same point.

We called out our team number to the monitoring point at Minto and continued on our way.

The only break I can remember in the monotony of river, trees, rocks, and more river was Fort Selkirk (432km), an old frontier outpost from the early european settlement of the Yukon. It was odd to paddle past some european style buildings with corrugated iron roofs and white picket fences in the middle of a vast amount of… nothing.

Terry Short and Dan Voss who were somewhere behind us in another K2 told us later that they stopped in at Selkirk for a quick look around and a bit of downtime. Terry posted a photo later of a sign warning people to stay clear of the other end of the camp because there was a mother bear and cub in residence.

If we weren’t racing, I would liked to have stopped at Selkirk for a look around. It was tempting even then, as we’d been going for so long without seeing anybody that it was hard to remember we were racing.

Two hours later, everything was going wrong.

Kate was falling asleep in the boat. We’d be paddling and she’d just stop for a moment. She hadn’t managed to get as much sleep as me at Carmacks and it was now taking it’s toll.

My left shoulder was starting to hurt. It’s an old injury from running – long story – and while it’s largley recovered, repetitive load eventually causes it to flare up beyond the point where ibuprofen can control it. In other events, I’ve had cause to stop and research the medically advised maximum dosage of ibuprofen because the number on the box just wasn’t cutting it.

Worse still, Kate’s right shoulder was starting to hurt. That was new and unwelcome. We only had one good pair of shoulders between us.

We persisted for another hour or so, making what progress we could. Ibuprofen wasn’t taking the edge off the shoulder pain, and because our pace was dropping, we were also getting colder, unable to maintain body temp.

That was the point where we seriously discussed evacuation. We were both hurting and worried that further miles could make injuries worse. What stopped us wasn’t the $500 per paddler we’d have to pay, or even the understanding that they would only evac us to the nearest road. The thing that stopped the discussion was that because we’d swapped our SPOT tracker for Erin’s InReach, I simply didn’t know how to send the SOS signal.

Evaluating our predicament, we decided that it was time to make an unplanned stop on the bank and see how the situation looked after an hour of sleep.

It took us a few kilometres to find a suitable spot to pull over. First we needed a beach that we could land on and we were surrounded by high river banks. Then we needed somewhere flat and grassy to lie down, without being too rocky to get comfortable. Finally, we wanted an island in the middle of the river, rather than a spot on the bank, reasoning that there were less likely to be bears on an island. Some trees to break the wind would be nice, as long as they weren’t thick enough to hide a bear.

Moving from bank to bank on the river, we were wasting too much time, deviating from our race line, looking for the perfect spot. We gave up and compromised on a sandbar with some whisps of grass and a row of trees on it’s windward side.

Pulling our mylar survival bags from their packets and using our PFDs as pillows we lay down on the cold sand to rest.

When I’ve used rescue blankets in the past, I’ve generally been disappointed, and had the strong opinion that they were one step short of useless. I soon realised that I’ve simply never been cold enough to appreciate their heat reflective goodness.

The inside of the bag was a cocoon of warmth. My body was still generating heat and I could feel it filling the air spaces around me in the survival bag. I was asleep in moments.

I woke to the sound of a loud “HUT!” from across the water. A voyageur canoe team was passing the sandbar and they’d swung close enough to see that we were OK. I think the “HUT” had been a polite way of letting us know they were there and to see if we were moving.

We’d been down for about 40 minutes. but I felt a thousand percent better for the break. My shoulder had stopped hurting and my head was clearer for the small respite. Kate was also feeling better.

I was shivering uncontrollably from the temperature, but that only lasted for a few minutes until we stuffed the survival bags roughly into the cockpits and pushed off into the current again.

The wind had been in our faces since we turned west some time after Minto. It was blowing consistently at what felt like 10-15knots and gusting a lot higher at times. The wind became the theme for the rest of the leg to the checkpoint at Coffee Creek.

It wasn’t a particularly strong wind. It was just relentless. The course of the river was a long straight westward line which was permanently into the head wind. By the time we reached Coffee Creek, we’d been pushing into that head wind for 19 hours.

Coffee Creek

The second mandatory rest stop is for three hours at the Coffee Creek mining camp. The part of the camp we saw consisted of a floating pontoon dock and a track leading up the hill away from the water.

We pulled up at the dock and the volunteers helped us haul our boat up a rough ramp to a staging area where it was lined up with other boats in the order we had arrived. First in, first out.

We recognised a few of the boats in the queue. We hadn’t seen anybody else for a couple of hours, but that would be true if they were more than 15 minutes ahead of us on the river.

The camp was a rough and ready assembly of shelters. Straight up the path from the dock, there were a cluster of portable toilets. That made sense with a couple of hundred paddlers stopping in at this remote checkpoint over the next two days. That thought made me appreciate the benefits of being amongst the first teams through.

To the right of the toilets, a pole tent was set up as a kitchen, and one of the volunteers was overseeing the pots of warm minestrone soup and oatmeal. There were bread rolls, some kind of biscuits, as well as a good supply of bottled water.

A little further into the camp, there was a trio of large blue poly tarps strung up as shelter for sleeping. We approached quietly to see a scattering of paddlers in various stages of restless sleep.

The campsite clearings had been cut back into the trees, providing shelter from the incessant wind which was still pushing hard into the faces of paddlers on the river. The tarps were actually a welcome respite from the sun which was beating down on the camp.

Laying our foil blankets out on the ground we were both asleep in moments, our PFDs lying on the ground beside us with the numbers facing up sot he officials could find us for the wake up call 30 minutes before departure.

Time had ceased to be meaningful. Looking back, I’m struggling to work out whether it was 2pm or 2am. I think we arrived at 5pm and left at 8pm. We were so far North now that the sun no longer went down and days merge seamlessly into one another. We wouldn’t see night again until we were back in Whitehorse.

Leaving Coffee Creek, we were feeling the fatigue, bordering on exhaustion. Sleep had been welcome, but we were making constant withdrawals from our energy reserves and the last 150kms to Dawson was going to be on an empty tank.

The wind was still in our faces but we would be turning north at the confluence of the White River, and hoped that after 24 hours of head wind, we’d finally be able to paddle in some occasional sheltered sections.

More river, rocks, trees, and hours ground past. The hills around us were slowly getting lower and the river was getting dramatically wider. In the miles of river behind us, channels in the river were generally split around single islands of gravel and sand held together by small trees and low shrubbery. They might be 100m long but were generally only 30-50 metres wide.

As the river opened out into a wider river valley, the braids began to spread wider across the valley floor. Individual channels were hundreds of metres wide and there were multiple islands across a group of river channels that were a kilometre or more from side to side.

Selecting the correct path became more important and the consequences of a bad decision would be measured in much larger increments. We were still running to the pink line on our GPS, trusting the route which had served us pretty well so far.

We had another cut coming up a few kilometres ahead. Again we had a couple of teams shadowing us down the river. Having squandered our tactical advantage on two prior shortcuts, we pulled over for a comfort stop and watched our pursuers veer off to what without our route would have been our most obvious path. As soon as they were irrevocably committed to the current in their chosen channel, we pulled out and veered off into a fast narrow channel that catapulted us back out into the main channel a few kilometres ahead of them.

White River

Our final shortcut opportunity was a few hours past the confluence with the White River.

The White River confluence brought a number of dramatic changes to the character of the river. The most welcome change was an escape from the interminable wind as we finally turned Northwards towards Dawson. We were able to shelter from the Westerly wind under the cliffs on the left bank, and were still only getting a light breeze when we crossed to the right. Behind us, other teams wouldn’t be so lucky. By the time we reached Dawson, the wind had turned to a Northerly and teams that had been pushing endlessly into a westerly were damned again by more headwinds on their next leg.

The White added a massive increase to the volume of the Yukon’s flow. Probably an additional 50%. The most distinctive feature of the confluence was the change in the river colour. True to it’s name, the White River runs white with ash deposited by volcanic activity long ago. When we’d left Whitehorse, the river had been almost crystal clear with an alpine blue tinge to the depths. Beyond Carmacks, it had been increasingly tinging towards brown as it eroded its way through softer terrain, disturbed by the melting snow of spring. Now it was white with particles of ash suspended in the water.

We’d know about the ash ahead of time, but the density of it was a bit of a surprise. Upriver, we’d been running with a fairly conservative volume of water onboard, two 1 litre bottles which we alternated between. As we emptied one, we’d fill it directly from the river and add a purification tablet, then let it sit while we drank from the alternate.

The purification tablets are almost tasteless, and unnoticeable when mixed with a flavoured electrolyte supplement. We’d discussed the water quality with a few people prior to the race and were reasonably confident that we could drink the water without any treatment. There were no industrial or agricultural sites on this part of the river, which only left a very low possibility of “Beaver Fever” aka Giardia.

The ultra racing wisdom is that dehydration is an immediate and serious threat to your health. Giardia is an ailment that takes 4-5 days to manifest and it can be fixed with a single pill.

With our on-tap water source now loded with suspended mineral supplements, I was keen to see how far downriver I could get with the two litres I’d refreshed just before the river turned. Hopefully it would be a little more diluted a few hours downriver. Kate was the first to test the water and described it as “gritty”.

The river was also noticeably wider after the confluence. Braided channels were now separated by large sweeping island of grass and shrubs. All around us, there were indications that the area would be frighteningly different when the thawing ice began to push down the valley. This was the sort of riverbed which would change dramatically from season to season as snowmelt carved new paths through soft gravel, or deposited debris and gravel mounds in channels of the previous season.

With huge lateral distances between channels on the river, the route options were quite diverse. Ocassionally, we would see another team in the distance following the conventional outside of the bend route. We were sticking to the little pink route line on our GPS, adjusting slightly within the channel it indicated. That was rarely the outside of the bend. Looking at the topographic maps display, it felt like we were carving kilometres off the total distance by choosing a line closer to the inside of the bends.

A couple of times, we would find ourselves in shallow water where a newly deposited deadfall tree was slowing the water enough to deposit a bank of gravel in the turbulence downstream. Others were having similar problems in other spots. One of the lead voyageurs had run a fast channel into a wide delta which had left them walking the next 2km, dragging their canoe through inches of water.

Approaching our final shortcut, we’d been duelling with a four person canoe. We’d traded the lead several times over 10-20kms without any decisive changes. I could see my pink line deviate from the main flow dramatically ahead and it looked like it would be a giant killer.

The voyageur team was making another run at us when the turn came up on our left. Fortunately the entry to the shortcut was a deceptively blind channel with no flow leading into a large log jam. Our pursuers were watching us closely, and changed course towards us for a few minutes. They seemed to be debating whether they should follow this K2 that was clearly about to do something completely unexpected. They’d entered the backwater pool behind us, but were slowing and hesitant.

Even though we were further into the backwater we couldn’t see a clear way out, the course on the map was actually a u-turn around an obstruction, back upstream before winding through some low islands and back out into the flow. Knowing they couldn’t see the clear exit, we passed the narrow entrance, paused and turned back, making as if we had realised a mistake and were headed back out of the backwater.

The voyageur saw us turn and jumped into action to seize the advantage of being closer to the main current. As they powered out of the slack water and committed to the downstream flow, we slowed, smiled, and made our own exit through a nearly invisible gap in the log jam.

The voyageur team were probably feeling very pleased with themselves, the main current was fast and their water was deep. Arguably, we were even happier having shaken off our pursuers and now on a path that was probably 5km shorter than theirs. Quickly our backwater was supplemented by small streams filtering through the gravel and picked up again to a full blown downstream flow. Whoever discovered this shortcut, had obviously spent some serious time on the ground searching through the non-obvious channels.

60 Mile

The last verbal monitoring point is at Sixty Mile Creek, which as far as I can tell, isn’t sixty miles from anywhere. The question of how it got its name remains a mystery.

The laminated sheet of race notes put it 637km from Whitehorse and only 69 kilometres from Dawson. We were tracking at a consistent 11-13kph so we had 6-7 hours left to paddle. My race notes were based on the same mapping as our pink route line which had served us well for so many kilometres. There had been a couple of segments which had been off by a few kilometres here and there, but it had been reliable for 630km. We knew the race was 700 to 715km depending on who you believed (this is not unusual with most official distances being measured from statutory distance markers, or an imaginary line drawn down the middle of a riverbed as it ran decades ago. Our actual distance for most races is out by 5-10% against the stated distance.).

Everything we knew was telling us that we had 69km left to go.

So why the fuck did we believe the race volunteer at Sixty Mile Creek who said we were 32 kilometres from Dawson?

Looking back, I can’t even explain why I bothered to ask the question. It was all there in front of me and it was all consistently saying we were 70km and around 7 hours from the finish.

I think I was just wanting to hear another human voice after so long out in the wilderness.

The 32km caused a brain snap. We wanted it to be true. We wanted it to be over. We’d had enough, and it needed to end.

It seems like a small thing, but being told we were 3 hours from the finish was monumental for us. We paddle thousands of kilometres each year in training. As a result, we have a very well developed sense of how much energy we are expending minute to minute, and how much energy we can burn for a given time distance to finish on empty.

With 3 hours to run, we lifted our pace to a level that would leave us running on fumes three hours downriver.

Even as we lifted, the befuddled braincells in the the depth of my brain were whispering that this was all wrong. The race notes said 69km. The GPS was showing we were 69 km short of the expected total, and the map ahead of us wasn’t quite right.

I’d zoomed out the GPS until I could see the end of the pink line in Dawson. The course ran straight ahead for half the visible map, and then turned 30 degrees right for the final run to Dawson. Looking at the river terrain stretching ahead of the boat, I could see a ridge running down from the hills on the right which seemed to match the terrain map. Still, there was something wrong… the scale indicator on the map was showing a 10km grid.

But the official had told us 32km. I’d asked him twice. And then I’d asked him if he meant miles. He’d repeated… 32km.

We’d done about 25km and from the checkpoint and the evidence was mounting that we weren’t where we wished we were.

Kate wasn’t interested in hearing my doubts. She wanted it to be over and another 37km was not part of that equation.

On the GPS, our location was barely shifting on the map despite the distance we were covering on the water.

Our pace was still elevated for a final push to the finish less than an hour away when the river took a major turn to the left, the terrain I’d been looking at on the map had been zoomed out too far to even see the 5km left bend that we were now on.

Realisation that we had 40km to go hit us like a Mack truck. Kate cried. I put my paddle down and we drifted dead in the current. We’d burned our energy reserves and our tanks were now empty.

Our mood was dark and dejected.

For a moment we even considered the fact that we could drift with the 6kph current for the last 40km and we’d still finish under the cutoff time. We’d lost interest in finishing in a good time, or placing well in our class. We mentally shifted to just finishing the distance. The idea that the YRQs big brother, the Yukon 1000 was also on our bucket list was completely discarded. We’d had enough of river, rocks and fucking xmas trees.

The idea of drifting to the finish line was gaining some traction as we plummeted into an emotional low simultaneously. Normally, Kate and I are on very different emotional rhythms. When I’m low, she’s high and pulls me along. When she’s low, I’m high. It’s rare for us to hit the same low. If we’d been closer to a road access point, we honestly may not have finished.

Fortunately, the nearest road was at the finish line in Dawson, so there was really only one way out of this horror show. We drifted some more while we ate some food and drank to try to retore some fuel to our depleted bodies.

We’d have drifted quite a long way if it hadn’t been for the horrible rudder on the boat which had the annoying characteristic of turning the boat around so that it drifted stern first, backwards, down the river. Then the damn thing went from drifting downstream, towards Dawson, to looping back upstream in an eddy on the side of the current flow.

The only way to end this was to finish it.

The next three hours were a long struggle. After our three hour charge we were shattered physically and emotionally.

The only highlight was a spectacular sunset/sunrise. We were too far north now for it to get dark. The sun dipped low on the horizon ahead of us until the red rays were splayed across the bottom of the clouds above us, turning the sky red and pink with warmth we weren’t really feeling inside. It hung there for about an hour and then rose up through the clouds again.

I remember thinking red sky at night was good news, and then wondering how to interpret red sky in the morning when it had never really been dark. The race would be over soon, so it was going to be a good day. I’d stick with that.

Watching the map on the GPS, it was tempting to interpret each left turn as the final left towards Dawson, but they were all at the wrong scale.

Dawson

True to the briefing, the landslide at Moosehead Slough is the first visual cue that we were on the final approach to Dawson. and soon we could see buildings, and suddenly there was a river ferry moored on the shoreline.

A small cluster of people on the shoreline cheered as we went past and an airhorn sounded somewhere, but there was no sign of anything we’d recognise as a finish line. We had stayed in the fast moving water on the left of the river, away from a slow eddy that was closer to the towns river frontage.

As we started to pass the moored ferry, we spotted the finish line flags on a small dock, necessitating a big u-turn and a fast ferry glide manouvre across the current to avoid being pushed past the finish by the river current.

We nudged the bow of the boat up onto a gravel beach and stopped. It was over.

Despite being broad daylight, it was 5am in Dawson and there were only a handful of people moving around and it took us a few minutes to work out who was who and where the u-haul with our dry clothes was parked.

The officials had set up in the band rotunda a few hundred metres upstream of the beach where we’d landed. That had probably been where we’d heard the air horn.

Retrieving our bags, we looked for somewhere covert to get changed, but were scooped up by a wonderful woman who suddenly took charge of getting us to our hotel.

“Where are you staying?”

“Get in my car. “

“Don’t worry about the seats, I’ve got dogs and grandchildren.”

Despite our feeble protests that we could walk to the hotel, she was hearing none of it and drove us, where she called the night manager who was still in bed. I can’t remember her name but Hurricane Linda springs to mind as she was definitely a force of nature that couldn’t be resisted.

While she was talking, we managed to get into the hotel foyer courtesy of another guest who was heading out. Our saviour informed the manager that we were now waiting in the foyer for her and she should hurry up because we were tired and cold, then she left to rescue some more paddlers from their confusion.

The manager arrived a few minutes later looking like the best part of her sleep had been seriously curtailed. she welcomed us politely and then equally politely made a point of opening the doors to let some fresh air into the foyer, before getting us a room key.

We’d been on the go for 75 hours, and in the same clothes for nearly 70 of that. I’d lobbed my running shoes, safety blankets, and a few other soiled items into the trash bin at the finish line. My lightweight running shoes had seen me comfortably through both The Texas Water Safari and the Yukon River Quest. They probably deserved to be immortalized in bronze, but they’d have to be soaked in bleach for a week before I could put them into a suitcase.

My running shoes were one of the more successful gear selections of our trip. A pair of ultralight trail shoes with good grip, enough sole to stand on a sharp rock without feeling anything, but thin enough on top that they didn’t hold too much water.

We made our way to our room, which was conspicuously one with an exterior door so we wouldn’t have to spend any more time in the foyer of the hotel. Our wet gear went into a couple of large trash sacks and we hit the showers followed by a long free fall into a deep sleep on the bed.

Waking up refreshed a few hours later, breakfast seemed like a good idea. Even though we weren’t hungry, we felt we needed to return to some kind of normal routine, starting with the first of three square meals a day. More importantly, meals that didn’t come in liquid form.

The town of Dawson is like a Hollywood movie set with western style building facades and wooden board walks lining dirt streets. If it wasn’t for the cars and trucks on the street, we’d have woken up thinking we’d been sucked back in time.

It was a short walk to the cafes about three streets back towards the river from our hotel. On the way a man came up and asked me a question, which I couldn’t understand. I shrugged and he repeated it twice before muttering something else and walking away in disgust. He was about 20 feet away before I realised he’d been speaking French and I wasn’t still delirious from the race.

Breakfast was eggs benedict and a big cup of hot chocolate. Kate had something else and a cup of hot chocolate.

The rest of the day was spent wandering around the town, checking for friends arriving at the finish, wandering through the gift shops, and exploring the towns quirky historic features.

There are a few eye catching clusters of buildings which seem to be in a state of slow motion collapse, frames twisted and buckled as buildings lean against each other. According to the information plaque, the town is built on rock-like permafrost. The catch is that once a house is placed over the top, it subtly changes the ground temperature beneath the flat foundations and the buildings begin to sink into the melted silt and sand that it freed by the thaw.

Newer buildings seemed to have broad, flat foundation piles, like you’d see on a house being relocated, and lots of ventilation under the floor to maintain the group temperature.

Dawson was the original capital city of the Yukon Territory during the Gold Rush in 1896, boasting a population of 40,000. Now it’s population is around 1300 with the territory capital having moved to Whitehorse in 1953. It’s now technically a town, officially referred to as The Town of The City of Dawson due to its history.

As the day passed, other teams would arrive in Dawson and each team brought with it a feeling that we were now part of something extraordinary. Out on the river in the last few hours, we’d struggled to hang on to our motivation for finishing the race. With a little sleep and a bit more energy, we were absorbing the mojo of the event from the other teams we’d bump into wandering around the town.

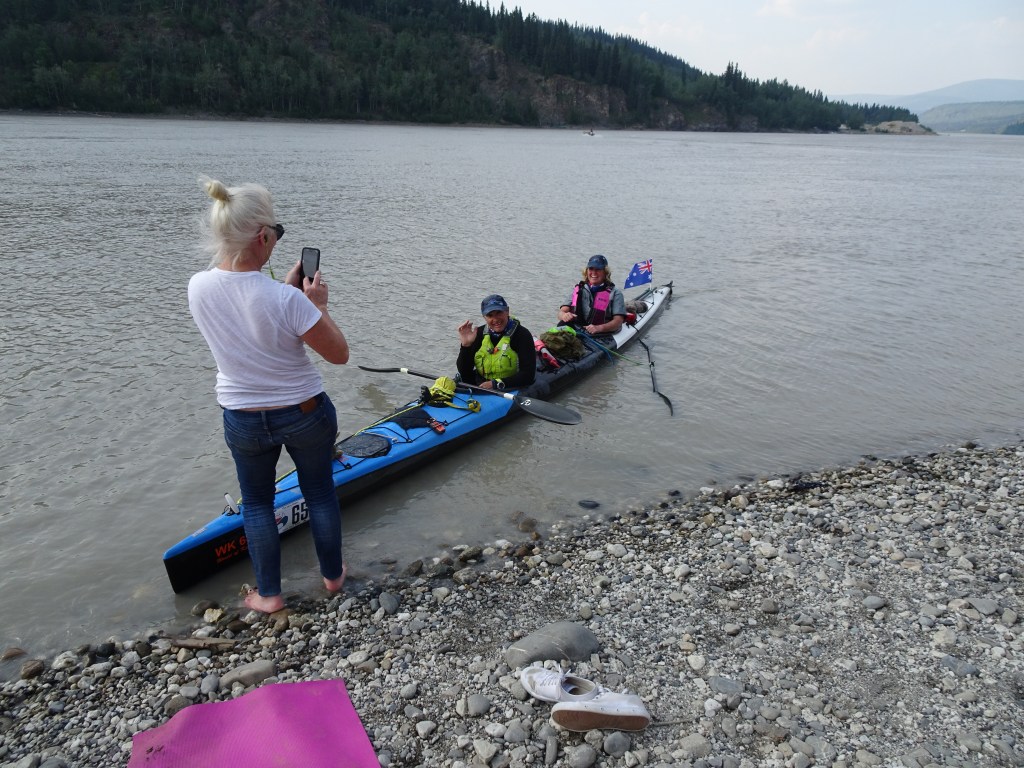

Stopping in to check the progress board posted at race HQ, we saw that Sue Smith and Greg Hillier were due to arrive in soon, so we grabbed an icecream and walked up onto the floodbank that protected the town from the river.

They were looking really tired as they came around the final bend to approach the finish line. They were on the right hand side of the river, opposite to our earlier approach, and they were slogging it out in the slow current we’d avoided.

I took a big breath and yelled “Aussie! Aussie! Aussie!”

“Oi! Oi! Oi!” echoed back from Sue. They were OK.

It wasn’t much of a stretch to walk the 300m to the beach and be there as they arrived. They were looking shattered. Sue climbed out of the boat telling us how great it was to see the big sign for Moosehide carved into the rocks on the hill above the town. We all looked up. There was no sign. Sue wasn’t hearing that. She pointed resolutely at the sign and confirmed she was seeing the word in big rock letters. We looked again. Squinted a little to see if it was the light and shrugged. Her hallucinations were definitely more persistent than ours.

I’d seen a Templar Knight with a lance and shield on horseback, following us down the river at one stage late in the last leg, and I couldn’t explain how my brain had been able to form that from the rocks and trees that were actually there. But I’d known it wasn’t real, it had just been an amusing aberration and a distraction from the long miles.

Sue was still claiming to see hers after a few hours sleep and some food.

Over the next 24 hours, the balance of the teams arrived in Dawson. There was an awards ceremony where we received a pair of cheques for being the second mixed K2 to finish.

The Kiwis who’d been not only the first mixed K2 home but also the first kayak team overall had been about ten hours faster than us. We’d been pretty well prepared, but the cold had been hard on us.

We talked to the Kiwis, Ian and Wendy a few times over the day. Dawson is a small town and it’s hard not to bump into everybody when you’re wandering around aimlessly. I suggested they should come to Australia in November and try their hand at the Murray Marathon, but they were pretty clear they preferred racing in cold climates.

A seven hour minivan ride back to Whitehorse was the final stage of our decompression from the Quest. We shared the ride with Terry and Dan, the two German guys who had finished ahead of us, and a Japanese driver who didn’t seem to have a lot of experience towing a trailer. There were a few white knuckled moments as the weight of the trailer began to push the rear end of the van around on a bend, but we all made it back to Whitehorse in one piece.

Whitehorse

We spent two more days in Whitehorse getting our gear cleaned up for the trip home. We got to spend Canada Day watching the parade and hanging out in the park, sampling pancakes and some Poutine for a little Canadian culture. It was also a chance to catch up with Erin for the last time and thank her for the support she gave us at the startline and later at Carmacks.

Despite how much we had trained, and how well prepared we thought we were going into the YRQ, it was at times a torturous event. There were definitely times in the race where we’d had enough and our motivation had switched from racing to finishing. Just after Minto and then again after the 32km point, we had hit rock bottom.

Looking back at those moments, we’d got through Minto with an hour of sleep on a sandbank in the middle of the river, and our crash at 32km had faded into the mist once we reached the finish line and got to share our experiences with the other teams who finished. They’d been miserable moments, but nothing that a little time and a bit of perspective couldn’t wash away.

By the time we left Whitehorse, we’d already picked out our boat for the 2020 YRQ and the longer Yukon 1000. Our entry is locked in for the 1000, and we’ll be waiting online on Friday to secure our place in the River Quest.

Watch this space…

After thoughts

It’s a long way and you need to be prepared for some highs and lows of morale. Our crash at 60 Mile was at the point where we were both at a low. Have a reason to finish.

Don’t cut corners with your gear. Substituting a small container for a bilge pump was a bad idea. Resist the temptation to thin your equipment out. It’s wild and remote. If you need your warm clothes, you will want to have your good gear.

The temperature varies a lot as you move through the day to twilight and into early morning. It also warms as you move north. We’ll be going back with more adjustable layers in 2020.

Make sure your next of kin know what to do if your SPOT tracker sends an alert.

Let your family and supporters know that it’s normal for SPOT trackers to stop transmitting during the event for lots of reasons.

Don’t over-tighten the battery cover on your SPOT. The organisers told us that was the most likely cause of our SPOT problems. The seal gets distorted. Water gets into the case. The SPOT starts sending messages on it’s own.

Have insurance for the whole event from arrival to departure. The drive home from Whitehorse was the scariest part.

We used a roll of duct tape during the race, to secure gear, emergency fixes to footrests, securing our bow lines, and fixing my foil survival bags.

It’s possible to do the event without a support crew. You can pay volunteers for support at Carmacks. The organisers will shuttle your bags to Carmacks and Dawson. And the outfitters provide shuttle services to get you back to Whitehorse. That said, we are immensely grateful to Erin who helped us during the event.

Refill your water before you get to the White River confluence. The water is a quite gritty from there to Dawson.

Enjoy the event as much as you can.

Never ask a random stranger for distances or directions. The official race distances are pretty accurate. Know them. Have them recorded somewhere on the boat and trust them.

Beware of using other peoples GPS tracks. The river changes from year to year. The water level also plays a huge part in which course you should choose. We were fortunate that 2019 was similar to our track from 2018.

Don’t stress about the bears ( your mileage may vary on that one)

Learn to pee in the boat without stopping. Practice too.

Don’t stress about paddling in the dark. It never got dark, and it was only dusky on the first night. After that, we were too far north.

The posted distances are pretty close to the actual distances paddled. We came in at 688km, which is mostly down to cutting corners.

| Checkpoint | Elapsed Time | Place | Plan km | Actual km |

| Whitehorse | Wed 12:00 | 11th | 0 | 0 |

| Policemans Pt | Wed 15:23 | 9th | 37 | 36 |

| Lower Laberge | Wed 20:42 | 9th | 88 | 88 |

| Big Salmon | Thu 3:57 | 189 | 186 | |

| Carmacks IN | Thu 11:10 | 15th | 304 | 297 |

| Carmacks OUT | Thu 18:10 | 15th | 304 | |

| Five Fingers | Thu 20:34 | 339 | 332 | |

| Yukon Crossing | Thu 21:34 | 354 | 348 | |

| Minto | Fri 00:24 | 394 | 385 | |

| Fort Selkirk | Fri 03:05 | 14th | 432 | 420 |

| Sandbar IN | Fri 04:23 | 441 | ||

| Sandbar OUT | Fri 05:19 | 441 | ||

| Coffee Ck IN | Fri 13:09 | 22nd | 552 | 522 |

| Coffee Ck OUT | Fri 16:09 | 22nd | 552 | |

| White River | Fri 19:39 | 584 | 568 | |

| 60 mile | Fri 23:40 | 637 | 621 | |

| Indian River | Sat 1:50 | 666 | 650 | |

| Dawson | Sat 5:10 | 25th | 706 | 688 |

Extra Stuff…

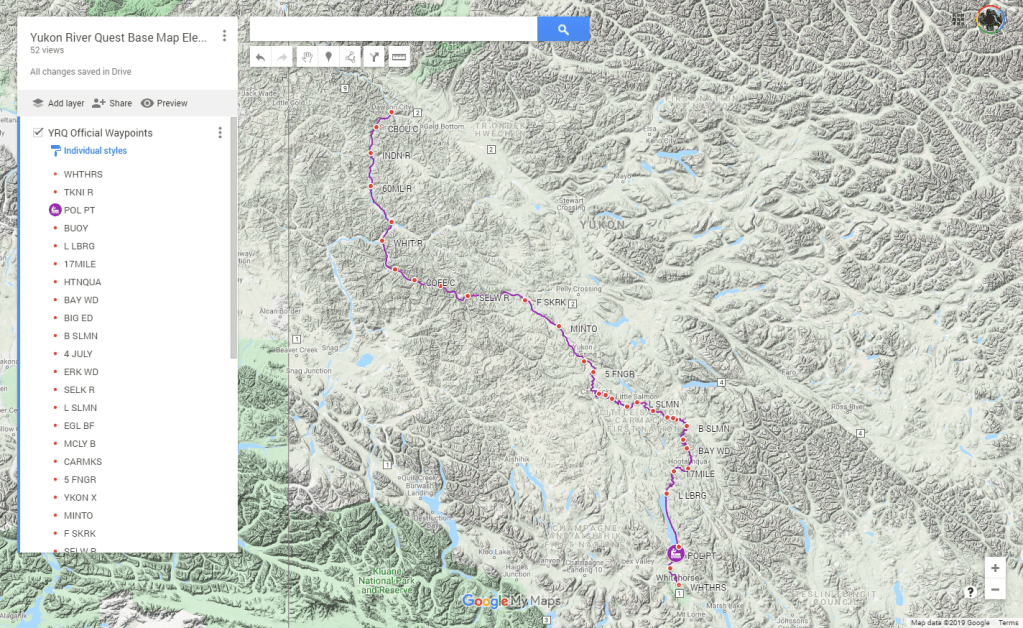

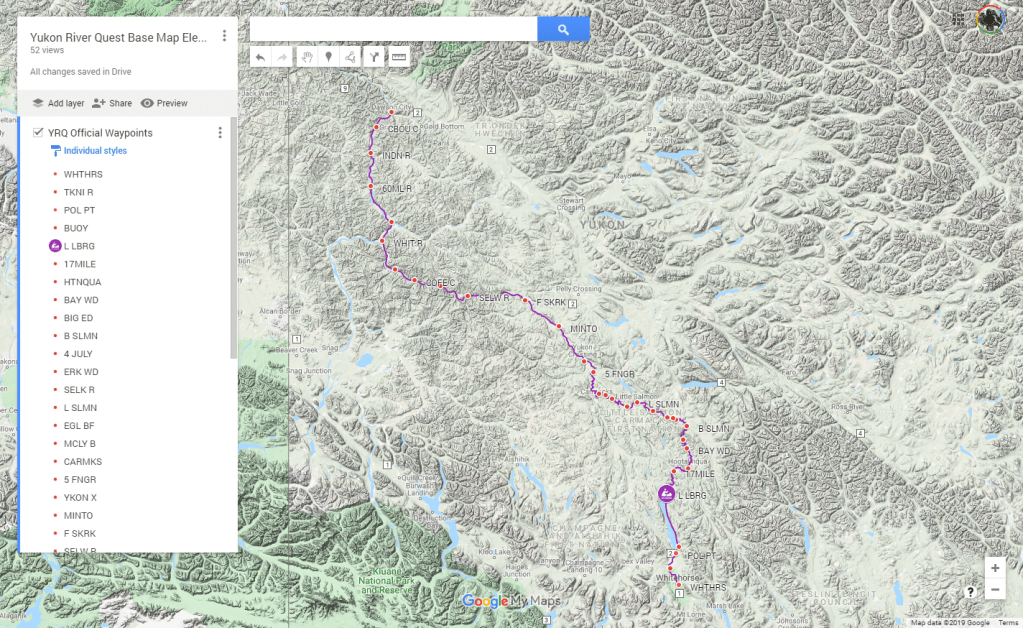

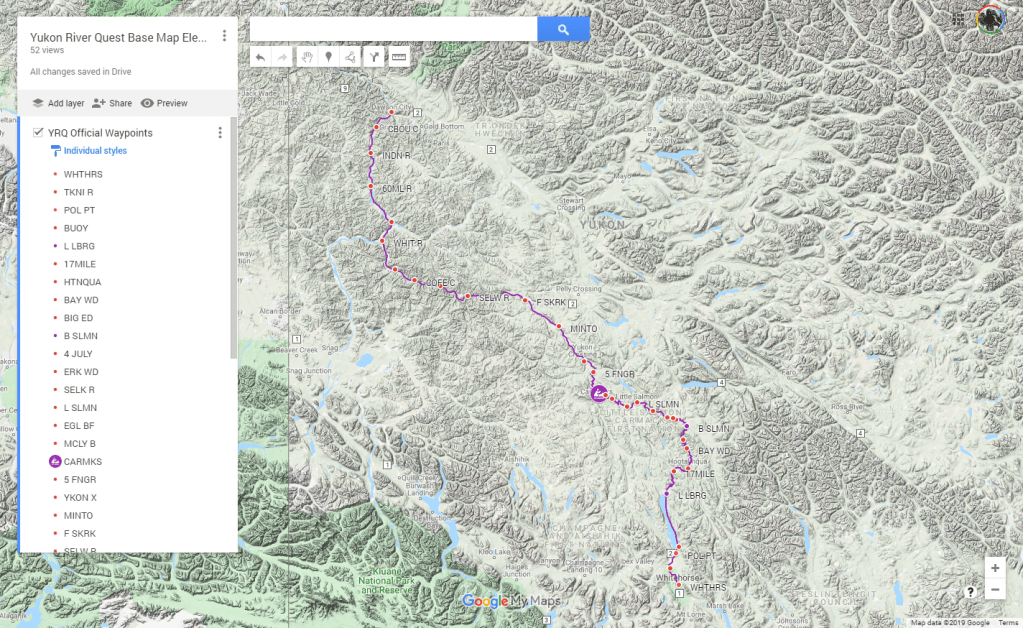

Maps

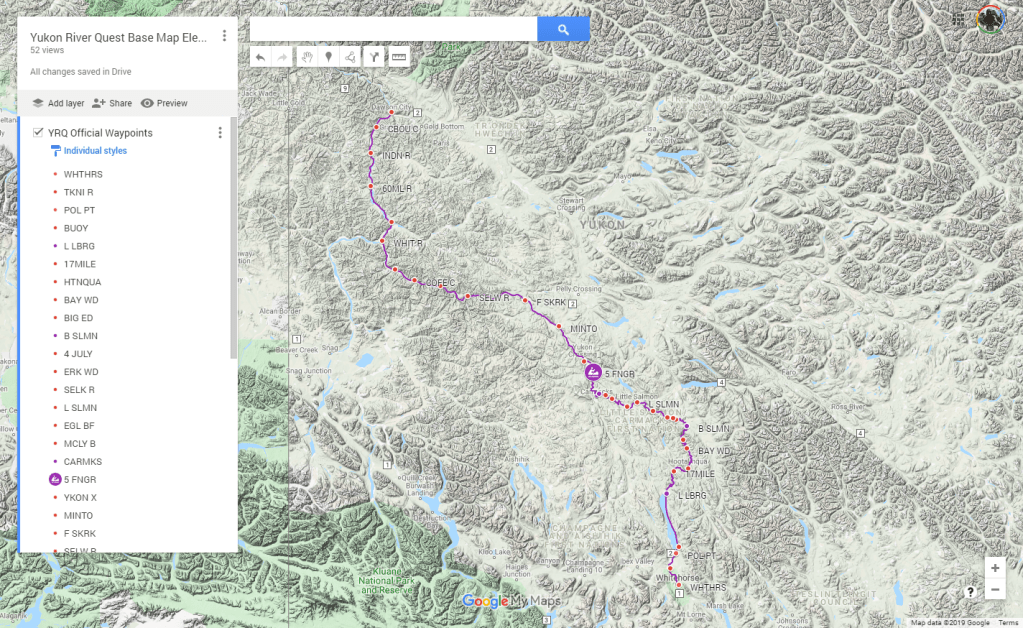

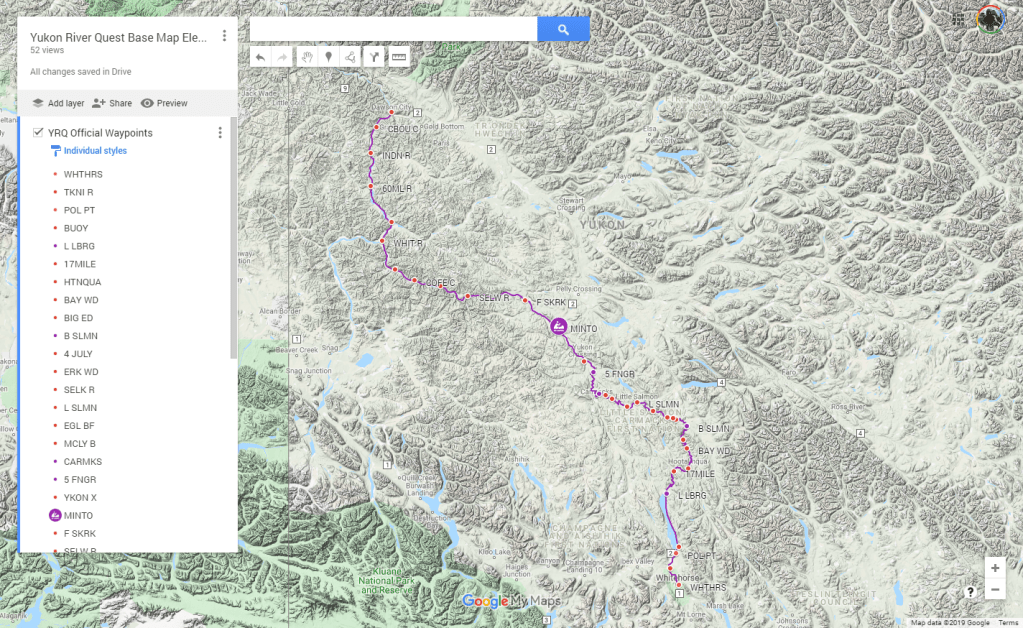

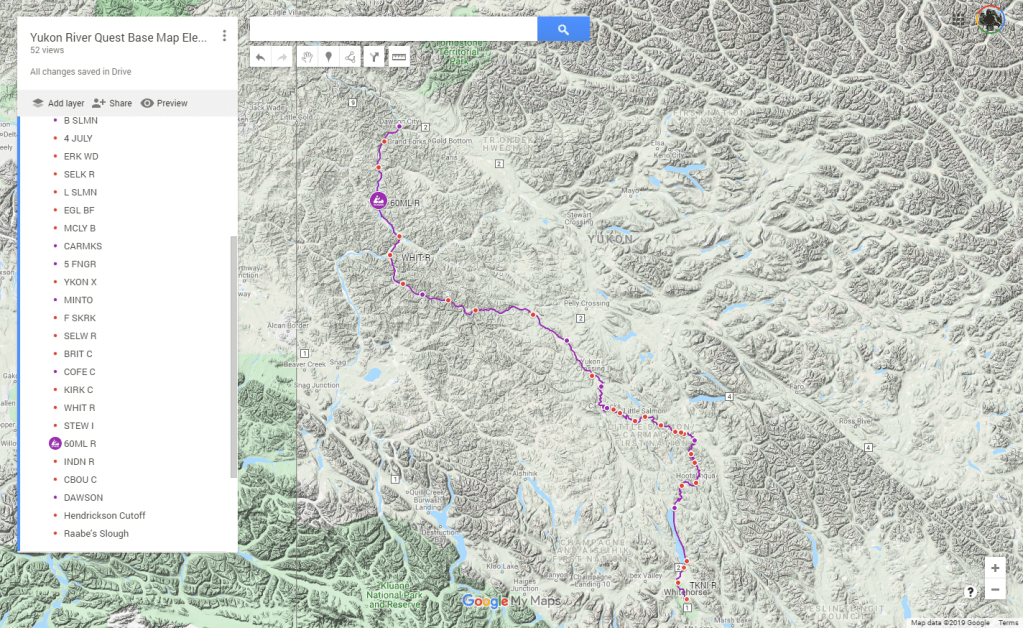

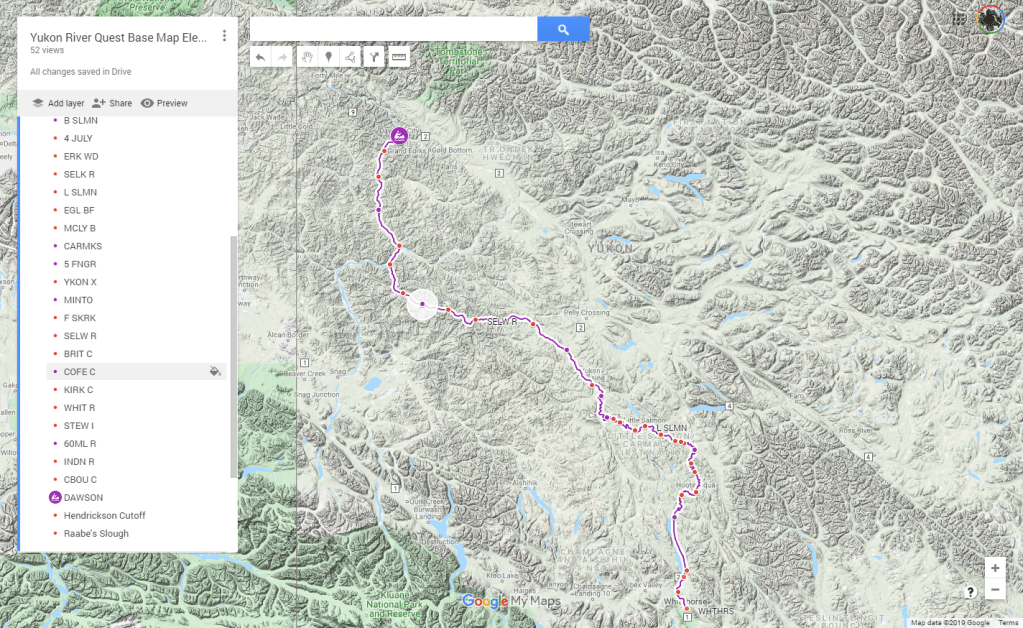

We’re returning to The Yukon for the YRQ in 2020, so I’m not releasing my target track until that’s finished. Watch this [link] on July 1st 2020.

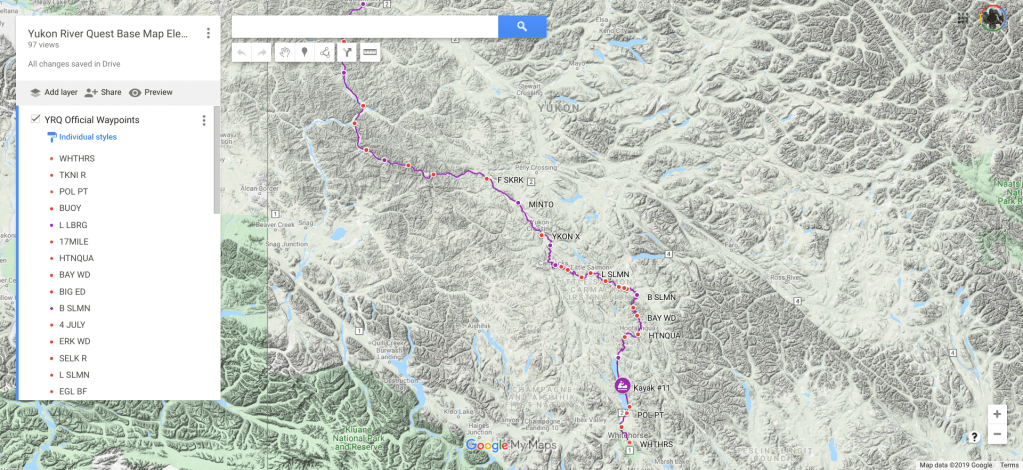

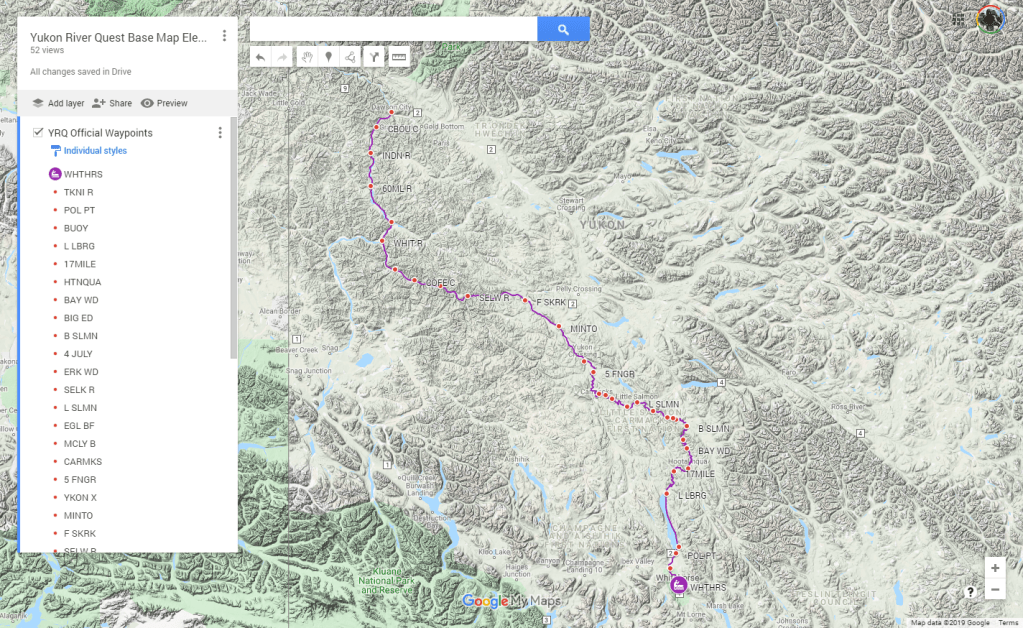

This is a GoogleMap of the course showing the checkpoint locations, and a usable track that has been shared elsewhere

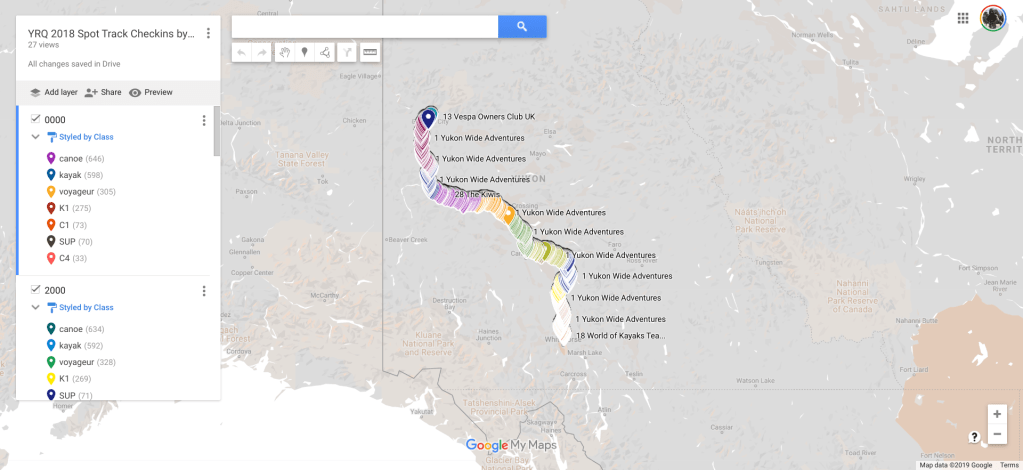

If you’d like to build your own map with all of your own shortcuts, here’s the map of all of the SPOT locations returned from 2018. It’s very large because there’s a huge number of individual points to plot. Don’t say I didn’t warn you. Click on the map image to open the Google Map

The GPS track from our boat on GarminConnect is shared [here]but it includes a number of unplanned stops to change clothes, pee, fix our rudder, sleep. We also hit some rocks and ran into shallows a couple of times.

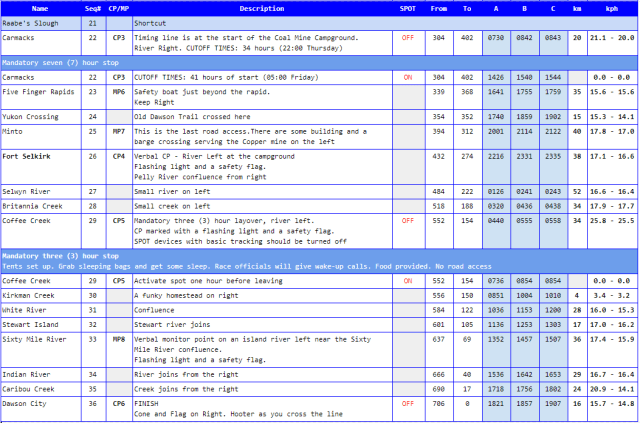

Race Notes

Here’s the sheet of race notes that I had stuck the the deck in front of my cockpit. It’s useful to have simple reminders when your brain starts to flame out.

Related Links

- Expedition Kayaks Podcast E.5 An interview with the Dawsons

- Cowboys and Aliens Facebook Page

- Yukon River Quest Home Page

- Yukon River Quest Tracker

- Yukon River Quest Facebook Page

- Kanoe People who are supplying our boat for the 2020 YRQ

- Yukon Wide Adventures who supplied our boat in 2019

Help encourage more posts by buying Steve a coffee…

Choose a small medium or large coffee (Stripe takes 10% and 1% goes to carbon reduction)

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Donate