Fort Yukon – Wind – Waves – Beaver – Bear

| Start time: | 4:36:00 |

| Altitude: | 136.2 metres |

| Time Stopped: | 6 hrs 58 mins |

My recollection of the river on day seven is that the low expanses of gravel were giving way to bigger islands and channels with steep banks, viewed from a low vantage point on a very large river.

In front of us was a large main channel with lesser anabranches1 leading off in random directions. That was the view from the cockpit. From our GPS mapping, we could see that our “main channel” was one of many similarly sized channels in a much larger universe of river that was obscured by islands. We’d escaped The Flats, where an expanse of water was interrupted by low islands, and had progressed to a new world where channels cut through land. We couldn’t see the forest for the trees, or in this case the other channels for the islands. Without maps or a GPS2 it would be easy to wander into one of the meandering oxbows, without ever suspecting you’d made a decision that had added 30km to your track.

Day seven was also a day for wind. The wind blew unhindered across the water, whipping up waves that splashed over our decks. It would be reasonable to say that the wind blew waves from all directions, but that was probably an illusion caused by the way the river looped. The wind direction was constant, while we paddled in a series of interconnected loops.

At some point in the morning, we came up on another team who were hugging the left bank. It looked like the waves and directions were making them uncomfortable. Whatever was going on, their unwillingness to make open water crossings was going to force them into a lot of extra kilometers. We lost sight of them a short time later as we cut from bank to bank, trying to run the shortest path we could find.

They were the first team we could confidently say we’d seen since the night before Circle. There had been fleeting sightings of paddle flashes and glimpses of what might have been other boats in the distance. More often than not, they’d resolved into trees or rocks as we got closer.

Train for race conditions: Over the 1000 miles, you will experience rough water somewhere it can’t be avoided. Almost certainly on Laberge, but probably on some part of the course from Circle to Dalton where the river is wide and exposed. Find somewhere to train that matches these conditions and get comfortable with A) Being 1000 metres from shore; B) Waves breaking over your deck and splashing to head height; C) Waves from 2 to 10 o’clock. Waves from the front (12 o’clock) are easy. 4 to 8 in a loaded boat, with a small rudder suck; D) doing a+b+c all at the same time for an hour or more. We have a training location where we can expose ourselves to those conditions while always having an exit route where we can get to shelter or turn to a less precarious bearing.

Early in the day, the river3 had been wide and windswept, flanked by gravel bars.

We spent some time contemplating what the flows would be like if the water level was a metre higher. We’d probably just be punching straight down the middle of the river instead of zigging and zagging around emergent shallows.

The wind made the shallows impossible to see, driving waves across the surface that completely obscured the clues that we needed to detect in order to navigate the weaving currents. Tinky’s natural tendency to follow the flow was put to good use. Mostly I stayed off the rudder pedals and let the bow sniff out the changes in direction that I couldn’t see for the waves.

In a couple of spots, we deliberately chose cuts which were not part of the natural flow. Lateral moves between channels which cut miles off some of the long oxbows or allowed us to transition from one chain of major flows to another. Occasionally those choices left us in shallow water, scraping the hull across gravel.

There’s a definite advantage to paddling a boat that you own and consider to be single-use rather than having to stress about the inevitable conversation with Thomas at the finish line when he sees the damage to his boat.

In one particularly memorable spot, we needed to enter a small parallel channel separated from the main flow by a shallow shoal. Leaving it too late to cross, we ran aground so I had to get out and drag the boat, Kate still seated, back into the deeper water then climb back in. We turned back upstream and had another go, allowing a bit more room for the hidden sandbar we’d hit. We did that twice before we finally gauged how far upstream the shallows really extended4. If the shortcut hadn’t been so significant, we would have lost time on the multiple attempts.

Overall, we think we had a good day. There was plenty of water and flow where we were paddling. There may have been better flows on other branches. There was no way we would know. The other channels were beyond our reach and visibilty.

Again, I don’t think you can fully comprehend the scale of the river and the effects on navigation without having experienced it. We were used to paddling on large bodies of water. Our training spot in Tasmania is 2 to 5 km wide, and we’re quite comfortable being a long way from shore. That paid dividends in the wind and across the broad sections where hugging the shore would have added miles to the route. The difference here was that there were four channels that were 1-2km wide and they each had their own anabranches that were big enough to be navigable rivers in their own respect.

Other than spotting that one other team, a touch of gravel rash and lots of wind waves, the day was unremarkable.

We paddled…

And paddled…

And then paddled some more5…

By the end of the day, we were around 110-120km from Dalton Bridge. We’d speculated6 through the day about whether it was possible to make it to the finish, but we were too far out. As a small consolation, we wouldn’t have to deal with the problem of being forced to pull up ridiculously close to Dalton. How frustrating would it be to be 10 or 20km from the finish as the mandatory stop kicked in?

We knew from speaking with Jon that he’d heavily penalised a team in 2023 for skipping the last stop and pushing through to the finish7.

For seven days now, we’d been dealing with the monotony of paddling across the truly massive landscape. Paddling towards a destination that was ever beyond the horizon. A destination that would still be beyond the horizon when yesterday’s horizon became the our new “here”.

Over more than a decade of paddling long distances, we’ve adopted a coping strategy of chunking the distance in front of us into familiar distances. Our club time trial was 5km. Our regular training paddle was 20, which is four time trials. There were bigger training paddles of 30, 40 and 50. The Hawkesbury Classic was three 30s, or two fifties, when you’re half way through, you just have to paddle the distance from Woronora to Chipping Norton and back. The strategy helps us pace and manage our energy budget by applying it to a distance we are familar with. It’s a good feeling to know you only have a time trial left to run as you approach the last 5km of the 404km Murray Marathon .

It was a good strategy for distances up to around 100km. But it was stretched to breaking when at the end of the day, you’ve moved imperceptably along a 1000 mile course8.

As the day wore on, the riverbanks continued to grind past without memorable features or landmarks. Months later I have recollections of parts of the river, but with so much distance covered in seven days, the latter sections fail to stand out.

Campsites were plentiful in this section of the river with low water levels exposing large gravel bars. Without the perspective of GPS maps, it would be easy to conclude that the riverbanks were part of the land and accessible to bears, but zooming out it was clear that most were islands surrounded on all sides by water.

This raises some questions…

When does an island become large enough to sustain a bear?

Do bears know that they don’t live on islands?

If we can’t tell that an island is an island, how would the bear know, being without a GPS map?

We’d had a good run with bear avoidance and should have guessed our luck couldn’t last forever.

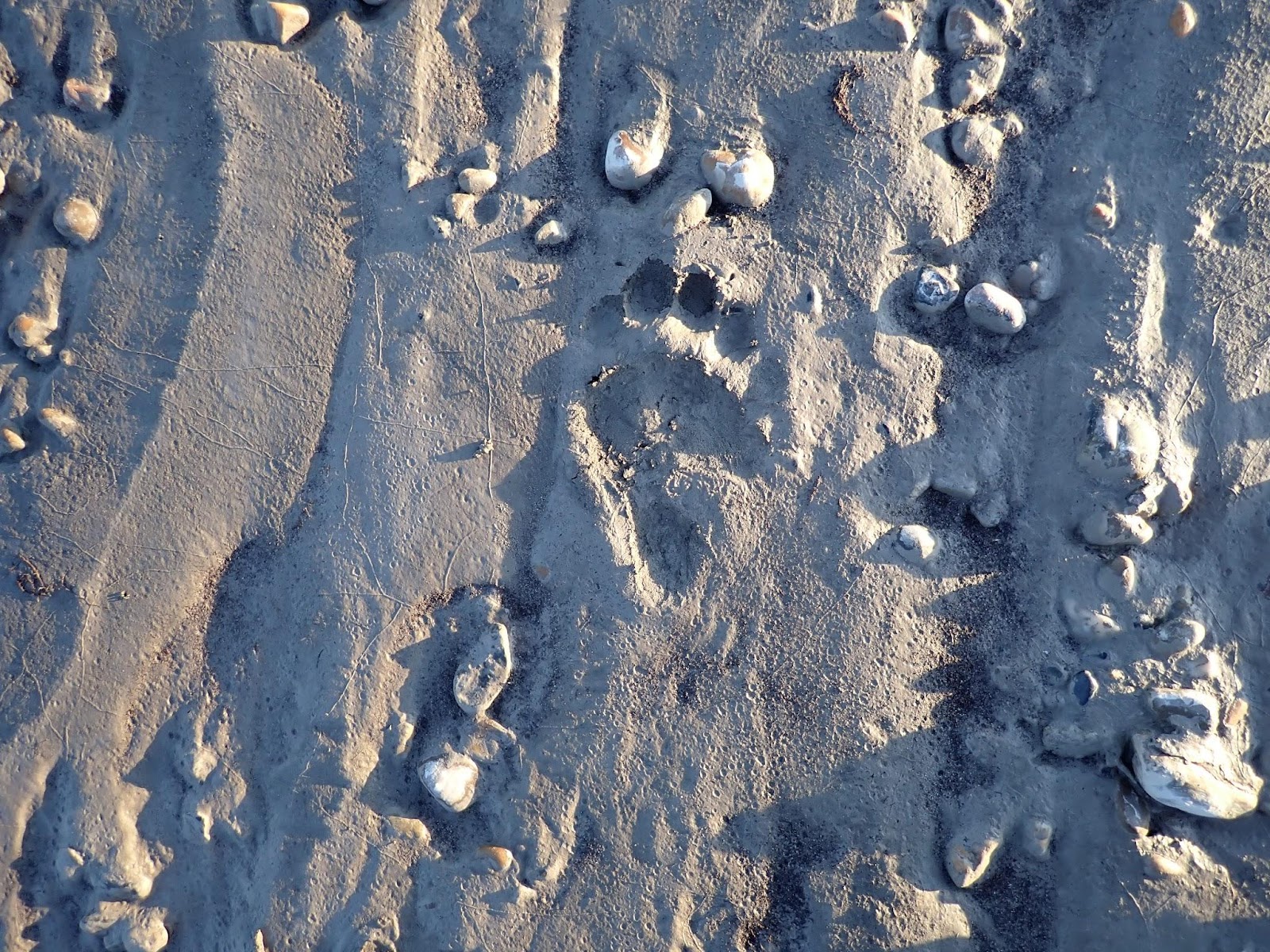

Pulling up on a promising bank, we jumped out of the boat, dragging it clear of the water before popping the hatches to grab out camp gear. Walking 30m across the gravel to a flat sandy spot that looked inviting, I was dismayed to see a number of distinctively shaped paw prints traversing the patch of sand. Bear prints.

What were the odds that a bear travelling across a very large gravel beach had happened to traverse the relatively tiny percentage of beach that would preserve their tracks for us to see? Looking at the gravel either side of the sand, there was no further evidence of the bears passing, but it was gravel which wouldn’t have recorded a track.

It didn’t appear to be the prints of a large bear, but we’re hardly experts on reading bear tracks9. The odds seemed higher that the small bear might be accompanied by another (larger) bear that didn’t walk on the sand. Would cubs still be travelling with their mothers? We were tired, confused, and frankly know very little about the seasonality of bear cub – bear mother relationships in the Northern Hemisphere.

What did cross my mind, which was addled by fatigue but not quite to the point of hallucinating was that if a bear had passed across a 3 metre patch of sand on a 60 metre beach then bears x beach divided by silt equalled 20 bears had walked along the beach! I wasn’t fatigue addled enough to think that was the correct answer to the algebra question, but the mere possiblity that n was greater than zero bears as proven by the starting conditions, was enough to reach a conclusion.

Not worth the risk. Our chosen beach was clearly accessible to bears, and at least one bear had been there recently. We still had time to find another campsite, even if we were close to the cutoff time10.

There wasn’t a lot of enthusiasm for dragging the boat back down to the water and climbing back into a wet seat that had cooled significantly while we’d been stopped, but BEARS!. Paddling a little stiffly, we continued down the river.

The next campsite we selected had much better separation from land, and no foliage (bare even) giving it a bear bearing capacity of zero. On the downside, it was a low shoal of silt and river gravel exposed by the low water. It lacked even a meagre patch of flat sand to pitch our tent, so we resorted to kicking the biggest stones away from a generally flat patch of gravel to create a tent site.

Having seen signs of bears in the area, we renewed our enthusiasm for taking the bear sprays out of the boat and keeping them within reach while we set up camp. We’d become pretty relaxed about that over the past week. We’d slept with the canisters beside us at night, but had been moving between the boat and tent without being too obsessive.

Another consideration for international competitors in the 1000 is that you need to buy bear spray when you arrive in Whitehorse, but have to discard it when you finish the race. Even if the airline would allow us to carry it, pepper spray is illegal in Australia. Australian Customs regulations are aimed at stopping the purse size self defence sprays. I dread to think of the conversation that would follow the discovery of a frat party sized pack of bear level concentrate in your checked baggage.

The same applies to the bear bangers. They needed to be disposed of before we flew out of Fairbanks.

The previous year, we’d left our bear deterrents with Thomas the outfitter who supplied our boat, partly to offset the damage we’d done to his shiny new boat11.

This year, we’d been thinking of a “trial deployment” at the finish line, the thinking being that after carrying them for several races, many days, and thousands of miles, we’d never actually tried them out and pulled the triggers.

Know your gear: Did you know that a large can of bear spray lasts just six seconds? Or that the effective range of the same can is six metres? That’s the length of your double kayak. Or that the top speed of a Grizzly Bear is 56km per hour? That’s two and a half boat lengths per second… Do you know there is a safety block that prevents you from discharging your bear spray accidentally that has to be removed before you can use it?12 Read the instructions.

Which brings us to a gravel bank in the middle of a river, miles from other humans, justifiably close to at least one bear, on the last night, with two cans of bear spray and six bear bangers that we were going to throw away the next day (Cost approx CAD$300).

The chance to deploy the bear spray, while enticing, was tempered by the wind swirling around us and anecdotes we’d heard about teams who had needed medical attention after deploying bear spray from within their tents. We were too close to the finish line to risk self inflicted injuries from spray drift.

The bear bangers on the other hand… We had six of them. They were surplus to requirements when we had pepper spray with clear sightlines in all directions. A couple less wouldn’t matter…

Bangers are pretty simple. There’s a launcher which looks like a zip-gun. A slim tube with a spring loaded fireing pin. You screw the banger onto the end, point that end away from your body, and towards the bear. You pull back the spring loaded slider with your thumb and let it go. An action familiar to anybody who’s ever clicked a ballpoint in a boring office meeting. I had plastic toy soldiers as a child and the field gun was almost identical.

Holding the launcher at arms length with the banger directed across the water, I released the trigger.

There was a satisfyingly large bang and a blur of something about the size of a ping pong ball that leapt 30ft out over the water.

I was halfway through a thought that it would probably be a startlingly dissausive experience for a bear to be on the receiving end of that blur, when the ball of motion stopped midflight and a nanosecond later exploded out to something the size of a volkswagen before collapsing on itself like a dying sun. The concussion hit me half a second later. Echoes rattled around the terrain for the next few seconds.

FUCK ME13!

To explain the intensity of the explosion, the echoes we heard were coming back despite no obvious banks or cliffs for them to be coming back from.

There is no doubt in my mind that if I’d been pointing it at a bear and the banger had hit the bear before exploding, the bear would either be very startled or very angry. Possibly both.

Thinking that the discharge had probably been heard by anybody within a two mile radius, we decided to abandon further experimentation in case it caused unwanted attention. We were somewhere between Beaver and Stevens villages with no idea of how close to people we might be. We’d spotted occasional signs of habitation on the riverbanks in the last few hours. Whether they were hunting lodges or permanent homes, we didn’t know.

Settling into our sleeping bags for what we hoped would be the last time on the race, I discovered that there was at least one rock, the size of my fist, which hadn’t been cleared from our tentsite. Throughout the night I alternated between using it like a tennis ball between my aching shoulders and curling around it in a foetal position.

| Stop time: | 22:46:56 |

| Moving time: | 18:10:56 |

| Distance: | 160.9 km (100.0 mi) |

| Average speed: | 8.9 kph |

| Campsite: | 66° 10′ 59.12″ N, 148° 7′ 50.77″ W (half way between Beaver and Steven’s Village) |

| Race Position: | 16th |

| Distance Completed: | 846 mi |

| Countermeasures Deployed: | 1 |

Help encourage more posts by buying Steve a coffee…

Choose a small medium or large coffee (Stripe takes 10% and 1% goes to carbon reduction)

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Donate- An anabranch is a section of a river or stream that diverts from the main channel or stem of the watercourse and rejoins the main stem downstream. Local anabranches can be the result of small islands in the watercourse. In larger anabranches, the flow can diverge for a distance of several or even hundreds of kilometers before rejoining the main channel. – Wikipedia ↩︎

- GPS scale becomes important as well. It can be easy view the channel you’re in as the entire river and have that view reinforced by reading and digital map that drops detail as you zoom out. We run Garmin eTrex 20 series devices because they’re rock solid, proven to be waterproof even in surf, and they run 72+ hours on a set of Lithium batteries. I run mine at 300m scale on the tight sections and 800m scale on open water. The 20 series does everything we need, but the 30 series has a magnetic compass. The 20 sucks if you’re stopped in a South Texas swamp at night trying to work out which way is South, because it calculated bearing from the difference in location readings. ↩︎

- “The River” at this point becomes the channel which we were on. That was our world view despite the larger river that existed beyond the wall of islands. ↩︎

- Each time, there was much swearing, accompanied by the sounds of gelcoat and fibreglass being gouged off the bottom of the boat. We’d considered selling the boat at the finish but after treating it quite badly (beating it like a red headed stepchild to use the vernacular) we didn’t think we could, in all good concsience, sell it for money. ↩︎

- It would be understandable for someone to read my account of the race and conclude that the event is jam packed with action and excitement. It is not. Each day consists of 1000 words describing the changes in landscape, 500 words describing the approach we took, and 50 words which try to make adjusting my seat cushion sound like the invention of heart transplant technology. Boredom is one of the biggest challenges you’ll need to face. ↩︎

- When I’m bored (see above), my mind turns to calculating speed over distance and esoteric measures like the winding factor of the river – how many miles of river do I travel to cover a mile as the crow flies. ↩︎

- They would argue they had reasons. Always remember that The Race Directors decision is final. ↩︎

- The distance is very foreboding when you leave Whitehorse. By Fort Yukon, you’re actually making meaningful progress each day. ↩︎

- The only bears in Australia are drop bears which being arboreal don’t leave tracks (or carcasses) ↩︎

- the rules allow you to relocate for reasons of safety (bears) ↩︎

- He’d still charged us, but it had been a fair price considering what we’d inflicted. ↩︎

- A friend’s daughter heard us talking on a zoom call about bear spray and asked whether you used it like mosquito spray by applying it to yourself. I’ve spent many hours since then, considering the merits of that approach. I know I can hit myself … ↩︎

- … as the hypnotist was heard to exclaim between stubbing his toe and never being allowed back on television. ↩︎

One thought on “2024 Yukon 1000 – Day 7 – Thursday”