Beaver – Stevens – Dalton – Closure

| Start time: | 5:27:00 |

| Altitude: | 113.7 metres |

| Time Stopped: | 6 hrs 40 mins |

It feels like the narrative of the last day should start with warm rays of sunshine beaming over the distant horizon or the soft golden glow of the early dawn, but we hadn’t seen a sunrise or a sunset for days. The endless arctic day continued and we continued paddling. There was no sign of wind and the sky was only lightly broken by high fluffy clouds.

“It’s 106 miles to Chicago, we got a full tank of gas, half a pack of cigarettes, it’s dark… and we’re wearing sunglasses.” – Elwood J Blues

In our case, we were 120km from Dalton. We were feeling like we had a full tank of gas. We had three more days of pain meds1. It hadn’t been dark for days. But we had sunglasses.

A distance of 120km is easily achievable for an 18 hour day. Probably 12 hours on flat water now that we could confidently empty the tank knowing that this was the last stretch.

Jon had said several times that the river picked up speed as it made its final descent to Dalton Bridge. He’d made a point that paddlers needed to be on the right hand side of the river as they approached Dalton Bridge to avoid missing the take out ramp under the northern end of the bridge. Looking at the maps we could see that the river consolidated into a single stream after Stevens Village and then entered a valley with steep sides for the last 40km. Considered collectively, we were looking forward to finding some of that promised speed for the final run to the finish line.

The course of the river had already become more organised, a major channel with only the occasional meandering side channels.

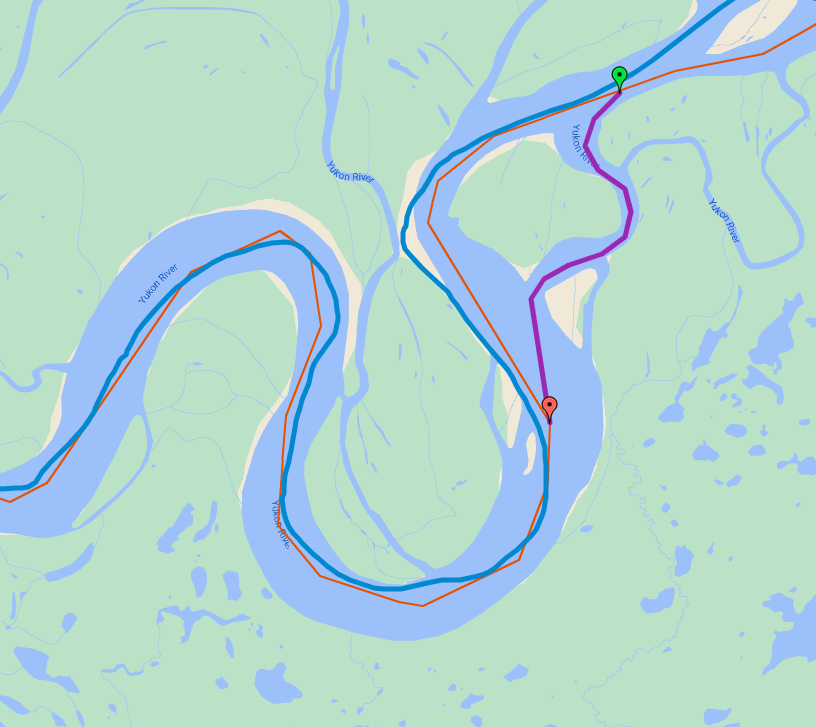

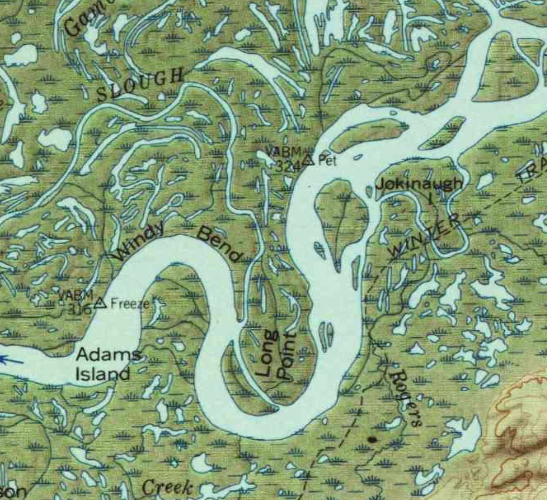

Twenty kilometers short of Stevens Village, we approached Long Point, the last shortcut we’d plotted on our mapping. The river ribbons around a long oxbow, hanging like an uvula2 from the main course of the river. The satellite and topo maps showed a washout that ran through the narrow neck of the oxbow. The course around the loop would be 12.5km, the shortcut was less than 2.5km.

The shortcut would save us just over an hour, but as we rounded the bend on our approach, we could see several red flags. Topographically it was a washout, where the river had cut a deep narrow channel through the soft soil at the neck of the oxbox. Rather than a clear channel that we could see through, the washout s-curved slowly into the hillside breaking the line of sight with a sharp reversal before rejoining the main flow.

Not having a clear line of sight through the channel was a problem. With the low water levels there was a heightened risk that a flood-formed channel would run dry as the water receded.

We swung wide towards the entrance of the shortcut, assessing it on the fly. The entrance was littered with trees collapsed from the eroded banks, but the entry line appeared clear.

The deciding factor was the lack of inflow to the cut. Running the eddy line between the main flow and where the side flow should be, I lifted off the steering and let Tinky sniff the currents. Maybe she could sense some flow that we couldn’t see…

Nothing.

If we’d been racing head to head with another team, on pace for a placing, or even a record, we’d probably have taken the chance (dependingbon the other team)3. Even with the obvious flow, the longer loop would add an hour to our elapsed time. But we were a long way off a fast pace, with nobody else in sight. The certainty of 12km down the main channel won out over a shortcut that could easily turn into 4 hours of dragging a heavy boat through a log jam.We’d run a conservative race plan, intent on collecting our t-shirts and finishing medals. There was simply no upside to dialling up the risk in the last 100km4.

A selection of map views for Long Point

Long Point is typical of the mapping challenge of the yukon 1000. Most of the maps show there is no way through the cut. Satellite imagery is either from winter when the river is frozen white, or at unknown water levels which may not be relevant to the river in front of us.

At a certain point, you simply have to paddle the river as you see it in front of you.

We went around.

Passing Stevens Village with a handful of visible buildings, we entered the final portion of the river. The anabranches collapsed into a single path as the river swung south for a few kilometres then a final right hand bend before entering the valley that ended at Dalton Bridge and the finish line where Jon would be waiting.

42 Kilometres lay in front of us. The distance of a marathon. Around four hours of paddling.

We waited for signs of the increased current Jon had promised. We couldn’t see any improvement on the GPS, but we remained optimistic that the narrowing banks and concentrated flows would combine to add some current.

A couple of flat bottomed river boats roared past us, heading upstream towards Stevens. We were getting close to civilisation.

It was a long four hours. The river didn’t speed up, and the wider expanse reduced the visual indication of speed.

Finally we caught a glimpse of the Southern end of the bridge appearing around a slight bend in the river bank. It seemed to take forever for the rest of the bridge to appear around the sweeping bend. We had plenty of time to consider the odd geometry of the bridge, which rises at a strange angle as it traverses from the low Northern bank to the hilltop on the South side.

There had been plenty of time to come up with something memorable to say to Jon at the finish. I’d had a few good ideas. At one point I’d come up with a monologue that I thought captured the journey.

“From the city of the white horse, travel north until the black bears turn brown. Follow the valley of fires until the river turns white with ash. Listen for the echoes of Service at the city of your ancestors, then continue north until the brown bears turn white. Then follow the sun that never sets until you find an Englishman beneath a bridge. He will be bearing rare cloth, rarer coin, and fine ale.”

What came out was “If challenging is the best word you can find to describe The Flats, you’re getting a fucking thesaurus for Xmas!”5.

Unfortunately, the camera wasn’t on for that and the following exchange, so what went down as our finish line interview was less passionately delivered.

We were handed a beer each, and then a can of something soft because Kate doesn’t drink beer. That cemented the receipt of two cold beers as the highlight of my day. For the final few hours, the dominant thought in my head had been whether the beer at the finish line would be cold or warm because we were late.

Still sitting in the boat with a cold beer(s), Jon shot a brief video sequence where we were asked how we felt.

Kate spoke about teamwork and having finally completed the 1000, ending a journey that started for us in 2019. I said something insane about actually enjoying it, and that the worst part of the whole experience was pulling cold wet pants back on each morning6.

I have a few additional thoughts on that for manufacturers of kayaking gear who advertise their clothing as hydrophobic. No, it’s not. It might bead a few water droplets for a while, but after you’ve been sitting in a wet seat for a day, it’s just soaking wet and cold. Hydrophobic literally means water-fearing. It doesn’t actually translate to water repellent, which is apt because the clothing isn’t.

Jon helped us out of the boat, took a few photos, and performed a reverential7 bestowal of our finishing awards. It was nice and appreciated.

We dragged our boat out of the water, transferred all the gear from the boat into our travel bags and collated all the trash from throughout the boat.

We were directed up a short dirt road to the river camp, with some instructions regarding free food and discount accommodation. First priority had been to pitch the tent and get the gear laid out in the sun to dry before we stowed it all for a long trip home. We’d figured that another sleep on the foam mats wouldn’t bother us after a shower and a good meal. The tent spots at Dalton are at the back of the accommodation blocks and a mixed bag of grass and tire ruts from people who have probably parked up on the grass and car camped. We were too tired to really care, and selected a spot that seemed palatial8 after the places we’d pitched for the past 8 days.

That was until the mosquitos. We’d been jokingly informed that the state bird of Alaska is the mosquito, but hadn’t seen a single one until we arrived at Dalton that afternoon. It may have been the abundance of prey in the area, but the camping spot was swarming with them and they were quick to land on any exposed skin.

We left the tent and gear drying and went back to the camp store to book a room for the night.

After a shower and a visit to the small room with the porcelain seating, we had a solid meal. Was it lunch, dinner, supper? Who knew, we didn’t even really know what time of day it was. The regularity of our meals had been thrown out by the constant need to stay fuelled to keep moving.

We wandered back down to the bridge to see who else was coming in. Another team in a canoe had beaten us into the finish by a small margin. They’d seen us but we hadn’t seen them, except maybe a few glimpses we’d dismissed as phantoms. The next team was due in a few hours and Jon was carefully monitoring the progress of the tail enders, who were touch and go for finishing inside the cutoff time.

Our boat was still on the gravel beside one of the boat trailers, so it was time to deal with our final logistical challenge, giving away a boat.

What followed was an intricate negotiation with Thomas, noting that the Passat had now completed its third 1000 which had undoubtedly cost him thousands of dollars in missed rentals as the default outfitter for the race. If he took it back to Whitehorse, he could give it to a canoe club or kids organisation and it would be out of contention for future races.

There had been some interest from racers interested in our boat for 2025, but we’d given Tink a pretty hard time on the gravel bars and didn’t feel happy about selling her, sight unseen, to anybody who would be relying on her to be in good condition for another 1000 miles9.

Pace yourself: From the day we withdrew from the 2023 race in Dawson, we’d been determined to finish in 2024. Our plan had been robust. Set a target time between record setting, and the cutoff. Divide the distance by that time and concentrate on staying on schedule, no slower, no faster. We finished 3 hours off our target, in good enough shape10 to paddle another 100011.

With all deference to the teams who enter to win or set a record12. First place gets a tshirt, a finishing medal and their names on a website almost nobody has ever heard of, until another team knocks it off13.

Last place gets a tshirt and a finishing medal too.

Everybody gets an amazing experience.

And a perspective that didn’t really land until I was back in the office with colleagues asking about the journey…

For almost two weeks, you are totally immersed in a universe of people who have the skills, training and resilience to complete a 1000 mile, 8 day, paddle race through a desolate bear infested wilderness. Returned to the mundane world of work, friends, and family, you are out-fucking-standing!

Don’t let any voice in your head tell you otherwise.

| Stop Time: | 17:52:33 |

| Moving Time: | 12:25:33 |

| Distance: | 116.8 km (72.6 mi) |

| Average Speed: | 9.3 kph |

| Campsite: | 65° 52′ 43.1″ N, 149° 43′ 14.3″ W (Dalton Bridge and the Yukon River Camp) |

| Final Race Position: | 15th |

| Total Distance Completed: | 1478km by GPS |

| Average Race Speed: | 11.6kph |

| Total Time: | 7 days 11 hours 22 minutes (29 hours 8 minutes inside the cutoff)14 |

| Total Moving Time: | 5 days 11 hours 1 minute |

| Total Stopped Time (6 nights): | 2 days 21 minutes |

| Final Altitude: | 85.6 metres (total descent 551 metres) |

Help encourage more posts by buying Steve a coffee…

Choose a small medium or large coffee (Stripe takes 10% and 1% goes to carbon reduction)

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Donate- After the race I had cause to read up on which of my anti inflamatories (or possibly the caffeine pills) had constipation as a side effect. ↩︎

- The dangly thing at the back of your mouth. ↩︎

- The trick here is to be just behind the other team. If they take the risk, you follow. If it doesn’t pay off, you’re equally disadvantaged. ↩︎

- We discovered at the finish line that several teams had taken the shortcut. It was clear and open. ↩︎

- Jon did in fact receive a thesaurus for Xmas. Ordering one in New Zealand, paid for from Australia, and having it delivered to Jon’s home proved to be more logistically challenging than most of the elements of the actual race, but a promise was kept. I look forward to 2025’s description of The Flats. Desolate and godforsaken would be appropriate. ↩︎

- I stand by this statement ↩︎

- There’s a bit of ceremony in the presentation which is fitting. If you want to know what’s involved go earn it. ↩︎

- It was flat, bigger than a door mat, with no rocks. ↩︎

- Fast forward to 2025 and we have just paid good money to rent the same boat back from Ben, who has replaced Thomas as the race outfitter. It transpired that none of the local organisations wanted a free double kayak and it got added to Thomas’s fleet before he sold the business. The only consolation is that we have an understanding with Ben that she’s no show pony and we are free to add to the existing damage with no recourse. ↩︎

- In case you haven’t noticed, I haven’t mentioned blisters since day 3. They were mostly healing up by the time we reached Dalton. Our only ailment at the finish was sunburn on the backs of our hands ↩︎

- Partly to answer the question of whether we could consider the Yukon 2000, a proposed race to the coast 1000 miles further on. Our conclusion is two-fold. Yes we could finish, and we could continue at that pace. ↩︎

- There’s an element of luck in setting any paddle race record. A team that draws a high water or flood year has a huge advantage. Records set in some Australian races may never be broken because officials would no longer allow the races to start in flood conditions ↩︎

- Between us, we’ve set about 15 race records in Australia, About 12 still stand. Every one is a target that will eventually fall. ↩︎

- Some of the times and maths throughout this yarn don’t reconcile. I’ve tried to align the GPS tracks with the race tracker and time zone shifts, but there are anomalies that just don’t line up. ↩︎

One thought on “2024 Yukon 1000 – Day 8 – Friday”