Crossing the border into Alaska – Eagle – CBP – towards Circle

| Start Time: | 14/07/2025 04:59:00 |

| Location: | 64°38’17.9160″N 140°52’58.3320″W |

| Rest Time: | 06:39:40 |

The kayak record for the Yukon 1000 is 5 days 11 hours set by Daniel Staudigel, Jason Magness in 2022.

Bob McLachlan and Gordon Townsend – Best Foot Forward NZ – were currently on track for 5 days 14 hours, which is a solid achievement in low water conditions. We were probably 500km behind them. Of course they had no idea we were that far back, and were undoubtedly wondering when we would overtake them.

Starting 10 km upstream from the border between Canada’s Yukon Territory and the United State of Alaska the day ahead promised a lot of paddling and few landmarks. The first 10 km would bring us to the border, a bend in the river with no markers or sign that it is anything special. Another 10 km and we’d reach the border checkpoint at Eagle Village. There we’d stop and check in with US Customs using a sat-phone bolted to the outside of a launderette. From Eagle it’s 75 km to Nation River where one of the larger tributaries meets the Yukon. Our map says there is some sort of structure on the riverbank. It might be a cabin, it might be an outhouse. It might be an glitch on the map, I saw nothing but trees as we paddled past.

There is a cabin 90 km further on at Slavens Roadhouse. Built in 1938 by a Frank Slaven it was a stopping point on the river until the 1950s. The Park Service restored it in the 90s for public use. The roadhouse reference has always bemused me. There is indeed a road, which runs a few miles up Coal Creek into the hills behind. It leads to not one, but two airstrips which we had programmed into our GPS in case of evacuation. The roads extend a few miles further into the hills before terminating at what are probably mining sites. In winter, Slavens Cabin is a stopping point for the Yukon Quest 1000-mile sled dog race.

After that our next notable landmark would be 75km downstream at Circle City. Population 91.

Being 260km from our start position, it would be a push to make Circle, even with the extra hour we’d pick up as we entered Alaska and a new time zone. We’d try to make Circle, but realistically 230km would be a good day on the river.

That’s a total of five notable landmarks over 260km, assuming we made Circle. Everything in between – nameless nothings.

Not actually true though. Before the Yukon River was “discovered” by Europeans in the 1840s, first nations peoples had been traveling the river for over 13,000 years. Reference the right historical map and you’ll find a name for every bend, oxbow, island and tributary from rivers to creeks. It seems that at some point somebody has lived, died, cut lumber, or panned for gold on almost every bend.

This section of the river is the final section documented in the Rourke Guide Books that canoe trekkers buy. The last booklet of the Rourke series covers Dawson to Circle. If we’d had it with us and bothered to use it, we’d have known that we’d spent the night on an unnamed island opposite Nester Creek after decamping from Hall Island because we’d spotted bear prints.

We don’t pay much heed to the minor features of the landscape during the race. They’d only clutter our maps. For day five we’d have little reason to refer to our paper maps. The river is wide, the path is mostly obvious. When faced with the occasional choice of channels around an island, a glance at the preset route on our GPS would determine left or right for the next 3-5km.

While researching our mapping for the race, I’d descended into more rabbit holes than a 9-11 conspiracist. I’d looked at written accounts by canoe trekkers, routes recorded by power boaters setting speed records, even a GPS trace from a pilot who’d flown the river from Eagle to Fort Yukon1. The deepest descent was when I was looking to map the deepest channel through The Flats from satellite imagery2, but that’s a story for day 6.

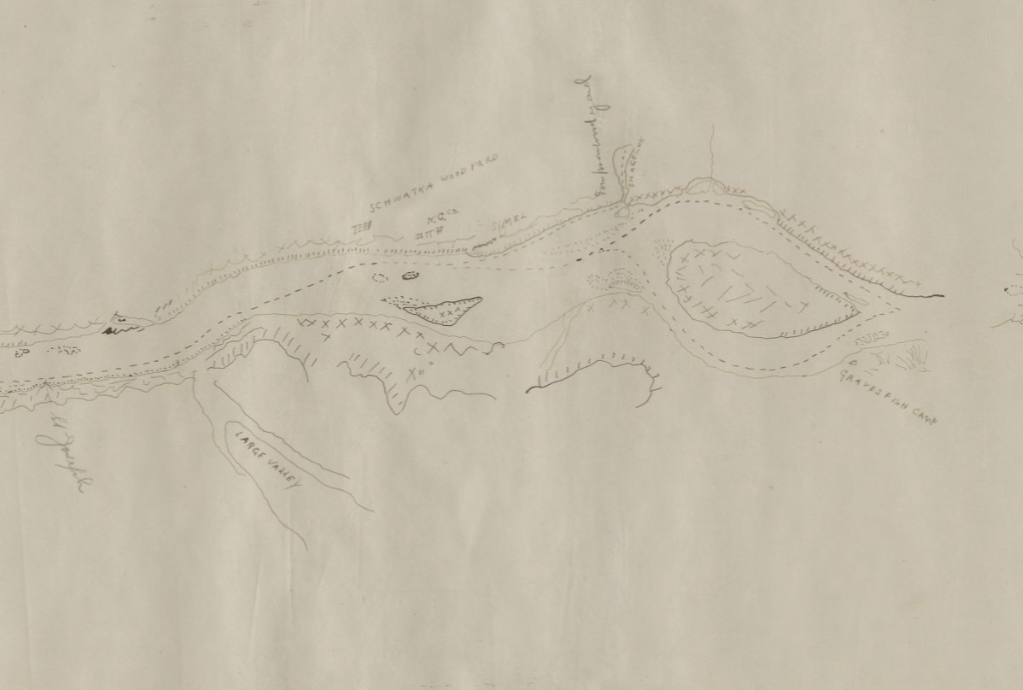

One charming find amongst all of that research was the discovery of a river pilot’s chart from the steamboat Leah which traveled the river until it was wrecked in 1906. It’s hand drawn on a continuous roll of paper. Rather than being a map projection on a grid, it runs as a continuous depiction of what the pilot would see to their left and right with their steamer as the centre of their perspective. Very cool.

Setting off at 5 am, oblivious that our shoal of silt and rocks was called Nester Creek, we covered the 10 km to the Alaskan border in 45 minutes.

On our GPS, the border between Canada and the US is a clearly marked red line that bisects the river at a latitude of 141 degrees west. It’s a line that starts at the St Elias mountains on the south coast of Alaska and runs dead straight along that meridian for 1000 km to the northern shore and the sea. In international boundary terms, it’s a line that says “There’s nothing and nobody here. Just rule a line, and we can go home”.

From the river, without the benefit of a GPS, you’d have no idea you were crossing the border. There’s no sign, no wall, no checkpoint. The checkpoint is 10 km further downriver at Eagle.

Because it feels like there should be some significance to crossing from Canada to the US, we did stop for a moment to have a drink and watch our clocks just back an hour. GPSs are remarkably accurate in that respect. Two GPSs and two GPS enabled watches each recognised the border and time change within 20 seconds of each other.

We were in Alaska.

Tell anybody in Australia that you’re going to Alaska3 and their first question will be about the snow or the ice. So you take a deep breath, and explain you’re not racing a sled dog team in the Iditarod, you’re racing a kayak down the Yukon River, which will be flowing because it’s summer in the Northern Hemisphere, and the temperatures will be in the mid 20s of the Celsius scale. Shorts and t-shirt weather, I’ll tell them.

So far, the Yukon4 was not living up to my predictions. We’d had several days of near continuous rain, some wind, the occasional thunderstorms, and when the sun had been visible, it was often through a haze of smoke.

From our campsite to the border, we’d had clear skies and an encouraging amount of sunlight without wind. The temperature was cool, but starting to rise so we were optimistic that the day ahead would finally serve up some decent weather. We’d pulled the wettest of our paddling gear out of the drybags5 in our cockpits and spread it out on the decks fore and aft to try and dry it.

It’s probably obvious by now that long hours on the river provide an opportunity for a considerable amount of thinking. Sometimes that thinking can be creative – last year I’d perfected a monologue I intended to deliver to Jon at the finish. When you’re in pain though, that thinking can turn quite destructive so it’s best to find things to distract you. I often find myself considering the great imponderables of the world, like why does it start to rain as soon as the shirt on my front deck becomes dry enough to pack away.

Touching on pain for a moment, I had developed a new problem which was at least distracting me from the pain in my wrist. A combination of clothing choice and sitting too far back in the seat had resulted me rubbing my spray deck between my sides and the back of the cockpit rim.

The applicable racing rule is “Everything that rubs will bleed”.

For the last four days, I’d been continually rubbing my sides against the cockpit rim with almost every stroke. Initially it had been some strokes, but as the days wore on and tiredness set in, I caught myself sitting back a little more each day and that had increased the rubbing. Overnight, I’d realised that the cause of this was the backrest on my seat not being correctly cinched up on it’s webbing strap. I’d come to this epiphany in the middle of the night as I’d rolled over and found myself glued to the liner of my sleeping bag by open wounds where I’d completely rubbed the skin off. There was a line across either side of my torso from the cockpit rim. Initially it had been a bit of inflamed skin, but the continual wet weather had us wearing jackets and thermals made of heavier fabrics and that had added to the damage.

It’s the paddle strokes. That repetitive twist and reach of the paddle stroke rubs over and over again. We run at a constant cadence of 72 strokes per minute. That’s our all day cadence in a heavy boat. Over an hour, even with a break, it’s just under 4000 rotations. In a 17 to 18 hour day on the Yukon, it’s 70,000 times your body rubs along the cockpit rim6. And it doesn’t stop once you’ve rubbed through your skin7. All I could do now that I’d broken skin was to sit up straight in a way that stopped it getting too much worse.

Broken skin presents two problems to a Yukon racer aside from the obvious need to stop it getting worse. Firstly, a kayak 5 days into a 1600 km race is not a sterile environment, so problem number one is keeping as much as possible of that environment outside the wound area. I’d solved that by applying a strip of 2 inch of Fixomul fixing tape across the abraded awathes of skin. It’s the sort of tape you normally apply to hold a non-stick gauze dressing in place, but when your medical supplies are limited to things you put in the kit before leaving Australia, you improvise and compromise. It seemed to be working as a barrier to further abrasion. It didn’t hurt too much going on.

The second problem is that inevitably, something does get through the protective barrier and into the wound, setting off an infection8. Infections have the potential to escalate badly in course of an event where you are persistently exhausted while alternating between silt-laden water and silt-covered campsites. More on that later.

The abrasion was the other reason I was hoping for a spell of warm weather. In warmer conditions I could strip down to a merino thermal or even the lycra rash shirt that was currently serving double-duty as a rain detector on my front deck. Whenever it rained, I’d be forced to bring out my heavier Goretex jacket with it’s coarse fabric again. Over the course of the day, we’d switch in an out of our rain gear a dozen times.

For the run into Eagle however, it remained pleasantly warm and dry.

As you approach Eagle, there are early signs of habitation. Flat-bottom boats with outboards pulled up on the shoreline. Ladders propped up on the shore, providing access to houses perched at the top of the bank. It’s clear that the river level is 4-6 metres higher for at least some part of the year.

Eagle Village itself sits above a steel flood barrier wall which stands about 5 metres high. There must have been a dock fixed to the base of the wall at some point. The remains of a flight of stairs poke out of a hole half way up the wall. The bottom step is just out of reach from the narrow rocky strip of land at the base of the wall.

We pulled up alongside the rocks to find that the current was ripping past at a fair clip and the river bottom dropped steeply into the water. On the shore side of the boat, it was knee deep. On the other side, the bottom was out of reach. While Kate held on to one of larger rocks, I climbed out and extracted the rope we had stowed on the fore deck. Looping the rope around a rock to tether the boat, Kate climbed out and we left the boat to bang around at the end of the tether while we looked for some path to the top of the vertical steel wall.

We’d been through Eagle the previous year, but the customs sat phone had been down so Jon had been waiting at the top of the bank, checking teams in with customs while he held us for 5 minutes at the bottom of the wall. We’d been told in the briefing about the path to the top being at the end of the wall, and where the customs phone was located, but we’d been spared the need to actually find it for ourselves.

This year the phone was working, so there was no urgency for Jon to make the long trek into Eagle which is 100 km up a dirt road where even Google Street View dares not go.

After casting around looking for what I’m sure Jon had described as a ramp, the route to the top turned out to be a barely discernible scramble up a near vertical spill of rocks and dirt ending in a thin spot in a wall of 8 ft bushes. Kate took a wrong turn while pushing through the bushes and had to follow the sound of my voice to escape.

Now at the top of the wall we remembered that the Eagle9 checkpoint wasn’t on Front St which runs along the top of the steel wall. The phone is in a booth attached to the side of the Launderette, which is on the next street back… Right? What we weren’t so sure about was how many blocks along we needed to go to find the launderette.

We wobbled10 up the street, skirting the hotel and took the first right turn that lead away from the water to get to the cross street further back from the water. Turning left at the next junction, we spied the launderette and located the phone booth on the farthest side.

Under a small porch-like overhang, there’s a yellow weather-proof cabinet, and inside the cabinet, there’s a old phone box style handset. It’s on a steel reinforced cord so short that you have to lean into the box to put the handset to your ear.

You pick up the phone and it rings. It was 7:16 am and I remembered reading somewhere that the border checkpoints were open from 8 am to 8 pm. I couldn’t remember Jon saying anything about it in the briefing, but I’m sure there used to be some thing in previous years about timing your arrival in Eagle to hit that window, or you’d have to wait11 12. The phone was answered on the third ring.

The exchange was brief, cordial, succinct. I gave them our team number and the agent asked for my full name and some details. Then he asked for Kate’s full name and some details. Satisfied with our identity, he recited some instructions to the effect that we were approved to enter the US, but that to complete the entry procedures, we needed to attend a CBP office in person, or we may be unable to enter the US in the future. We’d been told to expect this in the briefing. Then he asked which port of entry would be departing the US from13. When I said Fairbanks there was a loud cheer from the background on the agents end. Were the agents running some sort of office pool? Or were they in Anchorage and thrilled to know that we weren’t coming to them. Either way he seemed to be laughing quietly when he bid us farewell. Perhaps he was winning the pool?

Back to the water and and scrambling down the bank, we hauled the boat back to the shore by its tether and climbed back in to set off again, now legally permitted to be on the Stars and Stripes side of the border.

From Eagle, it’s 75 km to Nation River which is only noteworthy for being a vaguely recognizable tributary delta that breaks up what would otherwise be the 170 km between Eagle and Slavens Roadhouse.

At this point, it’s not just the distances down river that are large. Round a bend, and the reach to the next bend can be five, ten, or fifteen kilometers. The river is getting wider too. Coming into Eagle it’s regularly 500 m from bank to bank. By Nation River the breadth is one or even two kilometres as it sidles around groups of islands. Beyond Circle where the river spills into the endless braids of The Flats, the riverbed sprawls out to ten kilometres or more in places.

Doing a health self assessment, Kate’s wrist was quite bad but still on the manageable side of debilitating. The abrasions on my sides were OK as long as I didn’t slouch in the seat14. When Kate asked about my wrist, I thought about it for a moment, and offered that the feeling of the tendon passing through the bursa on the back of my wrist was like having a week old catheter pulled out by an angry ex who just found out I’d slept with her sister15. As I said earlier, there’s a lot of thinking time and this was the result of creative thoughts and dark painful thoughts combining over several hours. We decided we were both 5 out of 10 on the pain scale.

We were both fatigued. It wasn’t that we were especially tired. We’d had a reasonable amount of sleep and with our camp routine now refined, it was good quality sleep.

Part of it was boredom. Landmarks appeared in the distance as you rounded a bend and you’d spend the best part of an hour paddling a long reach to the next bend. There’s a complete lack of stimuli.

There were no hallucinations. We weren’t at the point of exhaustion where rocks turn into Hobbits or trees become elephants16, unbidden and persistent until you shook your head and forced them to resolve back into realities. We were at the point where Kate could point out a portrait of Elvis on a rock face, and I could see immediately which way Elvis was facing. No elephants though.

A few hours down river, we were making a diagonal crossing from a left hand bend to a right hand bend maybe 10 km ahead. We were a third of the way down the straight, and a third of the width from the bank when I caught my head rolling towards the water. Paddling on flat water is rhythmic to the point of being hypnotic17. I’d just fallen asleep and almost took us both into a capsize. Kate had noticed it too and was quite alarmed. I’m close to 100 kg. Kate’s closer to 50. If I tumbled into a capsize, she wouldn’t be able to stop us.

Another health and safety meeting was hastily convened. Kate admitted that she was also having micro-sleeps and had been missing occasional strokes. I’d noticed in my peripheral vision that her paddle stroke was slightly out of sync with mine, but I’d put that down to her wrist. I’d also felt the occasional break in her rhythm, discounting it as her moving around in the seat to relieve pressure points18. We were both doing that.

It wasn’t just the potential to capsize that concerned us, it was how far we were from shore on these big diagonals. Over a 10 km straight between bends, we were hundreds of metres from shore for most of the hour it took to traverse. A long way from shore, if we capsized we’d have to deal with a reentry from the cold water into a swamped kayak. The water was cold enough that we would definitely be wide awake, but gasping and shivering by the time we made it back into the boat and pumped it dry19.

Mark and Jules from Team Bristol Train had been enthusiastic about cold water acclimation in the days before the race. They’d arrived in Whitehorse a few days before us and begun a regimen of daily river plunges. I believe it was advice they’d picked up from Jake and Matty in team Untapped – but I might have that wrong.

Regardless, they would go down to the river each morning and submerge neck deep in the river, initially for moments, but slowly building up to 6 minutes (I think).

The idea behind the daily dips was that through acclimation to cold water, you can overcome the autonomic shock of sudden immersion, which in a capsize can cause an uncontrolled gasp reflex (very bad), rapid uncontrolled breathing (quite bad), and spiked heart rate or blood pressure (not good). With all or any of those things going on, complex tasks like clambering back into a kayak can quickly become impossible, and without a life-jacket you’ll probably drown quickly. With a life-jacket, you may still die slowly unless you get to shore, but your body will be easier to locate.

Uncharacteristically Serious Note: Wear a fucking life-jacket when you’re in a kayak or a canoe.

If you want to know more about cold water shock syndrome, I thoroughly recommend Moulton Avery’s National Center for Cold Water Safety. Start on this page and you’ll want to take an ice bath like Mark and Jules.

While Mark and Jules (and presumably Matt and Jake) had systematically mitigated the risks of cold water shock, which are real and present dangers on the Yukon 1000, Kate and I had not20.

We live and train in Tasmania where 363 days of the year the water is bloody cold, and the other days its colder. We’re the only ultra distance paddlers we know of in our home state and in the absence of buddies who think that a 5 hour paddle is a jolly way to spend both days of the weekend, we paddle alone. And we exclusively paddled doubles, which are three times the fun when it comes to self-rescue in the sort of conditions that will put you in the water.

So our primary mitigation for cold water shock is to not get in the cold water21. Our choice of the slow and stable Passat over the faster but wobblier WK 640s that other teams rented was the cornerstones of that avoidance. Falling asleep and sideways was probably the only thing that would cause a Passat to turn over on the water.

We slugged back a few caffeine pills to beat back the weariness. With no immediate sense that the pills were kicking in, we revised our navigation approach. Rather than a diagonal, which would commit us to mid river for long stretches, we ran closer to the banks, then made our crossings more directly and with a little more urgency, before running down the other bank.

This stretch from Eagle to Circle had come with a similar fog of fatigue last year. We’d pushed through it by talking. Talking seems like an obvious thing to do, but we’re married and have been for over 30 years. In that time, we’ve said pretty much everything we have to say, and we’re practiced at tuning out when we’ve heard it before.

Some teams pack music or podcasts, we generally just shut up and paddle.

Forced to talk about something novel to stay awake last year, we told each other about everything we could remember from birth to the time we met. It took us about 16 hours, back and forth. We both learned some things. Not much of it was from the category of [yawn] things I’ve heard before [yawn].

With no personal detail of my life left to disclose, and a perpetual ban on me talking about work, we needed some new distractions.

The first distraction that came to mind was the bear bangers… For the past three years we’ve supplemented the mandatory bear spray with a set of bear bangers because a can of bear spray gives you six seconds of spray at a effective range of 6m. For those who find metrics confusing, that’s the length of a kayak or a small pickup truck. With a top speed of 56km/hr – significantly faster than Usain Bolt – a grizzly bear will cover that distance in 4/10ths of a second. The only good part of that news is that your surviving partner will still have 5 seconds of bear spray left.

A bear banger pack contains a pen sized launcher. Basically a metal tube containing a firing pin on a spring. You screw one of the five flare rounds onto the launcher, pull the lever back and let the lever go to fire the flare. The pack comes with two large rounds and three small ones. Last year after a bear-print sighting, I’d felt justified in firing off one of the large banger rounds to let any bears in the area know we were not to be trifled with. The whiz and bang had been satisfactorily loud and we slept well that night in the knowledge that every bear for 5 miles knew where we were.

The smaller flare rounds remained an intriguingly unknown quantity. The sales assistant in the shop where we purchased the flares had suggested the smaller ones produced a screeching sound that would scare off a bear. The packaging indicated that they were signal flares that were visible for 3 km in daylight and up to 12 km at night.

The disparity between what the sales assistant had said and the words on the pack had been on my mind for a few hours when we hit one of our hourly pauses for food and drink. We were about 3 hours from Eagle Village and hadn’t seen any sign of people since. In front of us the valley stretched off into the distance for at least 10 km with no sign of people or even places where people might be able to pull up on a river bank. We were out in midstream, hundreds of metres from the shore in all directions. This seemed like an ideal time to try out a flare…

I fired off one of the small flares, aiming it an angle across the water, just to be sure that it wouldn’t be visible to some distant paddler we hadn’t spotted. There was a little pop, a fizzing little ball of green about the size of a golf ball arced up for 20 metres and then dropped into the water with a “phut!” It had been in the air for all of 5 seconds and I’d put it’s effective visible range at 300 metres, assuming the person was looking in the right direction at the time.

Myth busted. The sales assistant was full of crap. They were signal flares, and pretty anemic ones at that. If we needed bear bangers in the future, we’d skip the mixed medley and go straight to the six pack of bangy bangers.

With the universal mystery of the bear banger resolved, we continued paddling and boredom descended again.

I could feel Kate missing paddle strokes every so often and I’d catch myself doing the long “I’m not tired” blink as fatigue wrapped it’s tentacles around my wandering thoughts. We’d gone to the caffeine pills again, but they weren’t giving us the perk we needed in the absence of mental stimulus.

Past and present teams in the 1000 have packed music into their boats in the form of waterproof speakers and playlists. The Duckers had been playing theirs back on day 3 when they’d gone past. Other teams from previous years had survived22 on playlists composed entirely of Taylor Swift. One team had packed podcasts from a late show.

Kate and I had experimented with a waterproof speaker during a training session at home. Several problems emerged. To be loud enough for me in the front, because I’m facing away and may have a small amount of industrial hearing loss23, it was too loud for Kate’s liking. She couldn’t talk to me over the noise. Putting aside the acoustic problems, we simply couldn’t agree on a playlist that either of us was prepared to suffer for an 18 hours day. So we left the speaker at home.

With the micro-sleeps becoming concerningly frequent, something had to be done though…

Taking the initiative, I began to tell jokes. Again after 30 years of marriage Kate has heard most of my material in some context or another, so I was forced to dig deep into the archives for the kind of joke that had escaped a casual recounting. It needed to be a long rambling odyssey of a joke that I could tease out to ten or fifteen minutes. I would have exhausted the knock-knock jokes of the known universe before we reached the next bend in the river.

Over the next two hours, I think I did a serviceable rendition of Billy Connolly’s Ivan the Terrible when the circus came to Glasgow “, his monologues about joggers, prostate exams, ending with “Two Glasgow lads in Rome“. The next hour was filled with a series of yarns by Fred Dagg24, including “Hamlet“, “Flea Racing“, and “Cooking with Dagg“. The set finished with “The Gumboot Song“25

Marking my own homework, I thought I’d done a good job of recounting the great jokes of my youth26.

And that was the odd thing. I could clearly remember the tracks from Billy Connolly and Fred Dagg circa 1976, but I couldn’t think of a single thing recorded after 1987.

While we weren’t hallucinating, and felt that we were functioning at a fairly normal level of cognition, I’d probably have struggled with spelling a word like cognition at that point. In the words of Ricky Gervaise – “When you are dead, you do not know you are dead. The same applies when you are stupid.”

What I knew with certainty was that all the song lyrics I could recall were from before 1985 and mostly pre 1978.

The reason I knew these tracks so well was that in 1977 my family lost almost everything in a house fire. Along with rebuilding our home, dad went out and bought a brand new 3-in-1 stereo – the sort that came in a wood paneled cabinet and filled the corner of the living room opposite the new colour TV – also wood paneled. With the stereo came a collection of 78-rpm records which were a menagerie of music from Bill Haley and the Comets in 1954 to Boney M in 1978. I would hesitate to call it popular music or to acknowledge that it had been popular at any time. I don’t think he bought any more for the next 20 years, so this became my musical universe for the next 5 years until I went to high school. I played some of those records over and over until I knew them by heart, or at least by thought I did27.

For the next couple of hours the vast empty silence of the Yukon River was shattered by me singing the songs of my youth at the top of my lungs28. Occasionally it was the full song if the lyrics were horrifically memorable, but mostly just a few scrambled verses and a chorus.

I thought about assembling a playlist of shame, but honestly some of the songs in my head were too analogue and unloved29 to make it to Spotify.

- Rock Around The Clock – Bill Haley and The Comets

- La Bamba – Ritchie Valens

- The Pub With No Beer; Duncan; The Angel of Goulburn Hill – Slim Dusty (Dad was a big fan)

- Cheryl Moana Marie – John Rowles

- Rhinestone Cowboy; Galveston – Glenn Campbell

- Thank God I’m a Country Boy – John Denver

- Rivers of Babylon; Rasputin – Boney M (to this day I still think this one came free with the stereo)

- She Taught Me to Yodel – Frank Ifield30

- Tie Me Kangaroo Down; Jake the Peg; Two Little Boys – Rolfe Harris (Before the whole thing…)

- The Gambler – Kenny Rogers

- Puha and Pakeha; Rugby Racing and Beer; Short Back and Sides – Rod Derrit (none of which has aged well)

- A Little Goodbye – Roger Whittaker

- I am a Cider Drinker; Drink Drink Yer Zider Up; The Combine Harvester – The Wurzles31

- Lily the Pink; The Unicorn – The Irish Rovers

If any of those ring a bell, you’re old. If more than four of them are actually in your playlist, we can’t be friends.

Lost from memory were ABBA, Engelbert Humperdinck, Kamahl, Tex Morton and a plethora of country singers long dead and thankfully forgotten. Richard Clayderman, Acker Bilk, and The Glen Miller Orchestra (a black sleeved four record collection with silver embossed title) were instrumentals so Kate was spared those tracks that I haven’t thought about in 40 years.

My descent into musical misery came to an end as rain started to fall. Rain was followed by a fairly impressive period of thunder and lightning. The idea of being bug-zappered by lightning dispelled any last vestiges of fatigue and gave us something to focus on.

One thought going through our minds was how the other teams would react to lightning. For the 15 years we lived in Sydney, lightning was a common occurrence, and we have become a bit blasé about it. We did imagine that some of the other teams, if they were nearby, might decide to go to ground. But where exactly would you hide from lightning?

“You’re not safe in the open. You’re not safe under a tree. Choose wisely” had been the advice from the safety coordinator of The Murray Marathon back in 2018. When all your options are equally bad, you may as well carry on, moving targets being harder to hit.

We found out after the race that Mark and Julie from Bristol had chosen to shelter in their tent during one of the lightning storms. Like us, Mark and Rubio had pulled on their jackets and kept moving. I’m betting West would have been telling Paul how the lightning in Texas was so much bigger.

For the next few hours, the weather would continue to oscillate between sunshine and rain. Reluctant to lose time swapping in and out of our jackets, we’d ride out the first few minutes of each shower until we were sure it was going to persist. While our rain gear is quite heavy-duty and protects us well from both wind and rain, we would swelter in it when the sun came back out. Then as before we would delay stopping to change until we were sure we were clear of the rain. As the day wore on and the temperature dropped, every cycle of rain would leave us a little wetter and a little colder.

Kayaking is a water sport, and you should accept early in your journey that being wet is inevitable. Our rain shell layer was 80% stopping wind chill and 20% preventing absolute saturation. From the start of the race to the finish line, we would be wet to the core. The only time we were dry was in our sleeping gear, sleeping bags, and tent.

A sense of futility about wetness wasn’t enough to stop us trying to dry our spare paddle gear on the deck while we paddled. Every time the rash shirt on my front deck looked promisingly dry, water would drop from the heavens. With my thoughts clouded by a mix of fatigue and too much time with not enough to look at, I was starting to think that dry shirts caused rain – reversing cause and effect. If I wet my shirt, could I make the sun come out?

Approaching 9 pm, the rain was no longer coming in waves because it had settled to a relentless downpour. Kate was starting to succumb to the cold. Assessing the weather, the upcoming camping options, and Kate’s condition, we decided that we’d be stopping closer to 10 than 11. The abrasions on my sides were causing me a fair amount of discomfort as I was now constantly in my heavy rain gear.

For the next two hours there was a dearth of campsites. Nothing accessible or acceptable even with the low bar we had, being wet and cold.

It was 10:38 when we came across a broad flat apron of silt and gravel bordering a small creek that joined the river from the eastern bank. While we prefer islands, the low bank was barren and had good sight lines for 300 metres in all directions. We were cold and it was good enough.

Pulling the boat up on a part of the bank that was more gravel than silt we stepped out to find that most of the silty ground was saturated and water was puddling around our feet if we stopped moving. Moving further away from the boat and a few feet higher didn’t improve things much. The water table beneath the ground seemed to be sloping up into the hill and the source of the tributary. We settled on a flat tent site which was flat if we kicked the bigger stones away. At least it was dry.

As soon as the tent was up, Kate was into her dry camp thermals and into her sleeping bag. I was still fumbling around with the sat phone and first aid kit.

Hint: Teams are expected to keep their satphone turned on while they are in camp in case Jon needs to contact them. To receive a call the phone needs to be upright with the aerial deployed. We use a small string bag made for carrying a single wine bottle with a carabiner to hang the phone from the apex of the tent. It’s cheap, light, and it keeps your phone out of puddles on the floor.

Stripping off my outer layer of paddling gear, I’d discovered that the tape I’d used to cover the abrasion had done its job, but had in turn created a new problem with the skin on the edges of the tape now inflamed and about to tear open. After a day of rain, sweat and dirt, I figured I needed to remove the tape apply some antiseptic and let the abrasions dry out overnight. Peeling off the tape, the wound underneath was a mix of angry red skin and yellow-green discharges – not as bad as I’d expected. I thought pulling the tape off the open grazes would rate as my least happy memory of the race, but that would turn out to be rolling over in the middle of the night to find that my thermal top had adhered to the grazes as they’d dried. That really sucked.

Hint: Dry powder antiseptic is a game changer. If you use ointments, they hurt like Hell to apply and make the area around a wound greasy when you’re trying to apply a dressing. Dry powder is applied by puffing it onto the wound. It sticks to the wound and doesn’t affect dressing adhesion.

Our campsite was slightly less than 50 km from Circle Village, the gateway to the Yukon Flats. For all our improvements this year, we were 17 km further downriver than we’d been at the same time the previous year. In some respects we were paddling better, despite the injuries. The river and weather were definitely serving up tougher conditions.

This is the reality of the Yukon 1000, the river conditions play a big part in determining your final time. You don’t know when you enter whether you’ll get a low-water slog or a high-water luge ride. Like many distance races, you can guess the high water years from the years the records are set32. It would be hard to break a record in 2025.

Tomorrow we’d be in The Flats, a section of the river that I’d invested a year into studying maps and satellite imagery for. We had a detailed route33, multiple alternates, and potential backups. For day 6, we’d be changing up a gear.

| End Time | 14/07/2025 22:38:09 |

| End Location: | 65°29’11.6160″N 143°40’38.1000″W |

| Altitude: | 242.0 m |

| Distance: | 216 km |

| Paddling Time: | 17:41:57 |

| Non-moving time: | 00:41:13 – dealing with the border check point |

| Average Speed: | 12.2 kph |

| Max Speed: | 18 kph |

| Race Position: | 9th (down 1) |

Help encourage more posts by buying Steve a coffee…

Choose a small medium or large coffee (Stripe takes 10% and 1% goes to carbon reduction)

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Donate- That track had really confused me at first because it hadn’t been well labeled. It became clear when I worked out that the person who had filed it on Strava had been averaging 300 km per hour, 1000 ft above the river. Not a kayaker. ↩︎

- Don’t pretend you’re serious about mapping The Flats until you know the satellite tasking cost of two passes with green-LIDAR to determine the depth of the thalweg ↩︎

- I’ve given up telling people that our race starts in the Yukon Territory. Nobody in Australia could point to the Yukon on a map. Nobody. So we say we’re going to Alaska. ↩︎

- The Yukon aka “The bit of Canada bordering on Alaska” as my friends and colleagues in Australia would describe it ↩︎

- The cockpit dry bags were no longer dry bags in any respect. Everything in them was saturated and their only remaining purpose was to maintain separation between the wet sweaty clothes inside the bag and the wetness and other bodily fluids which were sloshing round the bilges. Ultra-marathon is not a glamour sport. I’ll illustrate that up with a great bit of advice from a Missouri River racer who says “don’t pee in your pants until you’re within seven hours of the finish” ↩︎

- Well over 500,000 strokes by Dalton Bridge. ↩︎

- By the finish in 2024, I’d worn holes in a cordura (ballistic nylon) spray deck and the bottom of my life jacket. ↩︎

- We were packing two types of prescribed antibiotics in our first aid pack, as well as giardia treatments in case we happened to drink the water. ↩︎

- Eagle population 82 sports a hotel, a launderette and a number of amenities that suggest unwarranted optimism in its tourist potential ↩︎

- Even though we’d only been in the boat for two hours, land legs take some time to come back ↩︎

- The 8am to 8pm opening time still applies at Poke Creek on the highway between Dawson YT and Tok AK on the way to Fairbanks. The instructions for that crossing are clear. If you arrive outside those times, DO NOT CONTINUE. Given the convivial nature of North American ports of entry since February 2024 (no judgement), we weren’t going to take any chances. ↩︎

- There’s also an airfield at Eagle which receives incoming flights from Canada. The instructions on the CBP website for the airfield state that all aircraft must be inspected by CBP prior to landing at Eagle (if you don’t believe me…https://www.cbp.gov) ↩︎

- English is weird right? I’ve just been asked which port of entry I was exiting from… and it seems perfectly sensible. ↩︎

- Shouldn’t slouch anyway, good paddling position is sitting upright or slightly forward, but we’d been in the boat non-stop for a lot of hours and slouch happens. ↩︎

- This is completely imagined and not something I could claim to have personal experience of. Later that night at camp I got her to put her finger on my wrist to feel the tendon lurch sickeningly through when I flexed my wrist. We stopped talking about wrists after that. ↩︎

- Kate said later that she did see some elephants, but they were hiding in the trees. ↩︎

- I’ve almost given up on GoPro videos of paddling because I fall asleep editing them ↩︎

- From the front seat, the rear paddler is about 2 metres behind the front paddler. The rear paddler can see what the front is doing. That’s why it’s the rear’s job to keep in time. The front paddler can’t see, they can only feel what’s going on. At the extremes of my peripheral vision, I could sometimes see the shadow of Kate’s paddle beside me. ↩︎

- We do carry a hand bilge pump for such an event. We’d prefer not to use it. ↩︎

- Both the teams who took cold water dips ended up taking cold water swims. Do with that what you will. ↩︎

- Before anybody panics, we can both eskimo roll, both single and double kayaks, and we have a few other party tricks in reserve. ↩︎

- Some teams seem to resort to music as a way to stay awake, other as a way to avoid having to talk to each other. ↩︎

- I tested perfectly OK in an auditory test leading Kate to diagnose domestic hearing loss, which is more of an attention deficit. ↩︎

- Australians would recognise (and typically claim as their own) satirist John Clarke (29 July 1948 – 9 April 2017) who’s invented character Fred Dagg was the defining influence of my sense of humour from age 7 and a half. ↩︎

- I didn’t know it until I was writing this account that John Clarke’s “Gumboot Song” is a modified version of Billy Connolly’s “If It Wasna For Your Wellies” ↩︎

- It was actually a bit average after listening to the real tracks again, but it was good enough for open mic night at a comedy club as long as it was happy hour. ↩︎

- A mondegreen is the term for song lyrics that are substituted according to what the listener thought they heard eg “Sweet Dreams Are Made Of Cheese” by the Eurythmics. You’ve learned a word today. ↩︎

- I have no singing ability. My high school music teacher thought I was taking the piss to get out of choir until she heard me doing what I genuinely thought was signing at a party. She asked me to stop. All I have to offer the music world is misdirected enthusiasm and considerable volume. ↩︎

- And in a couple of cases no longer socially acceptable ↩︎

- thankfully the Fred Dagg version which includes no actual yodeling ↩︎

- Somewhere I’m sure, there is a music critic who has described the Wurzles as “Genre Defining” ↩︎

- Not disparaging the teams who have set records in high water years. They broke the records that were also set in good conditions. ↩︎

- Over the 1500km of route we have planned, there is a single pink line to follow. That route is broken into 50km segments, and includes major alternates and shortcuts that we’ve identified from the mapping. The route for the 130 km of The Flats contains more points and turns than the other 1370km combined. For every piece of river, there’s a primary route plus 1-3 alternates, major markers every 10 km and breadcrumb markers which we would use to return to course if we needed to divert around an unexpected obstruction. We’ve invested a lot of time in mapping The Flats to spend less time paddling The Flats. ↩︎

2 thoughts on “2025 Yukon 1000 – Day 5 – Monday”