Success on the Flats – Fort Yukon – Other Teams – Improved Position – Humiliation on a sandbar – Sleeping in a puddle (Cutoff Slough)

| Start Time: | 15/07/2025 05:41:55 |

| Location: | 65°29’11.6160″N 143°40’38.1000″W |

| Rest Time: | 07:03:46 |

Twas a dark and stormy night…

Well… not dark, because we were now well above the Arctic Circle, where the concept of night only exists if you are prepared to accept that for a new day to start, the previous day must come to an end. Night, however brief, must lie between those two things. In the endless daylight of the far north, night is when you sleep1. We’d been paddling for 14 hours, and it felt like we were owed a night by somebody in charge, some time in the next few hours.

But it was stormy, and it had been for much of the day since we’d left our campsite 50 km south of Circle. The rain, which had fallen almost continually all night, was now being driven by increasingly strong winds.

This would be a good point in the narrative to point out some anomalies in the geography.

The village of Circle (65°49′31″N 144°03′43″W) isn’t on or inside the Arctic Circle. Circle is currently2 80 km (50 miles) south of the region it was named for. In a trope repeated by explorers and pioneers around the world, Circle was named by a group of miners in the 1850s who weren’t where they thought they were.

Fort Yukon (66°34′3″N 145°15′23″W) is 8 miles inside the Arctic Circle, and always will be because the current tilt is just part of a 40,000 year wobble, which will reverse before Fort Yukon leaves the circle3.

The Arctic Circle, in 2025, is a notional line around the Earth at 66°33′47.5′′N. This is because the axial tilt of the Earth to the sun is 23.5°. For every location North of this line, the sun never rises at the Winter Solstice and never sets at the Summer Solstice.

We will spend our 6th day between Circle that isn’t in the Circle and Fort Yukon which is.

So back to our dark and stormy night…

We hadn’t seen another team since the Duckers slipped past us as we were packing our boat at the start of day 4. We’d paddled the last 600 km alone. But now, as we were approaching Fort Yukon and the northern-most point of the race, we had caught sight of what appeared to be a canoe ahead of us. We’d caught a few flashes of colour against the treeline and decided it was probably red life jackets. Canoes are generally harder to see at a distance than kayaks because their paddles stay low, and you don’t see the flash of sunlight on raised wet blades that you see with a kayak.

The first sightings had been at an extreme distance, and the canoe had been in and out of sight as both our boats threaded different paths through the islands and bars of The Flats. We were inexorably gaining on them. Over the course of an hour, the pixel of colour in the distance had resolved into a two-person canoe. We could see the paddles occasionally on alternate sides of the boat. In the heavy crosswind, the paddlers were spending most of their time paddling on one side to keep their boat straight.

We were almost certain the canoe was another race team, not just because they were moving at a hurried pace, but because the weather was so bad that any sensible touring paddler would have pitched their tent and spent the day reading a book4.

Without really meaning to, we’d picked up our pace. There was no discussion about it, but the idea that we were catching another team in The Flats gave us a boost.

The day had started on a much lower note…

When we switched on our GPS units in the morning, we were shocked to discover they were no longer displaying the topographic maps of Alaska or the pink line that represented our planned course. This was dire. I’m pretty confident we could navigate almost all of the river from Whitehorse to Dalton by sight and memory, except for the section that lay in front of us this day – The Flats.

Both GPSs had been working fine the previous day. We’d been using the Alaskan topographic maps and the course track for most of day 5 past Eagle Village. Now they were gone5.

We’d had some trouble with one GPS6 pre-race in Whitehorse. I’d switched it on to find that the detailed topographic maps were missing. Kate’s was OK, but the micro-SD card in mine that held the detailed topographic maps was apparently corrupt.

I consider myself to be pretty GPS-savvy. We’ve been using GPSs to navigate kayak races since 2012 when raced the Hawkesbury Canoe Classic north of Sydney for the first time. Paddlers in the Hawkesbury use GPS because the race is run at night, usually a moonless night, and the river is too wide to navigate with lights on your boat7, so you run in pitch darkness with what you hope is a very accurate GPS track8.

Other teams had pre-race problems with their GPSs getting the necessary maps to load and then loading their tracks, which for 1000 miles can be very large and complex.

Our Yukon 1000 mapping is a dataset I’ve been refining since 2019, when we were first accepted to the 2020 Yukon 1000 for the first time. That event was unfortunately canceled by COVID. We’d used those same maps in 2023 until we’d withdrawn at Dawson. Then again successfully in 2024. Each time, I’d refined the maps to reflect the knowledge of the river that I’d gained along the way.

We use Garmin eTrex 22x GPSs. They have a small screen, but they are seriously rugged and have great battery life if you run them on lithium batteries. While they’ve been very reliable in the field, they can be temperamental to set up initially. Over the years, I’ve learned how to get the maps and data onto the device without resorting to human sacrifices.

Key to that reliable process was the Windows desktop computer back at home in Tasmania. We were traveling so light for the race that we didn’t have a laptop, let alone the Garmin Basecamp software that I needed to reload the GPS. Loading the licensed Garmin topographic map onto a new micro-SD card requires a laptop, Garmin software, and a good internet link. The topographic maps for the Yukon and Alaska run to about 13GB which took 7 hours to download when I did it at home.

Without that setup, our pre-race preparation devolved into a convoluted process involving a new micro-SD card and some shuffling between Kate’s good GPS, my phone, and a new micro-SD card that was ultimately installed in my GPS. That allowed me to copy our course and key locations like airfields9 and villages to my GPS.

Because the Garmin topographic maps are licensed and keyed to each device, you can’t simply copy them from one to the other and I wasn’t about to buy another copy of an expensive map I already owned. To solve this, I used a public access PC at the Whitehorse Public Library to download a free set of OpenStreetMap (OSM) maps. I’d been experimenting with them at home, and they were still stored in my cloud account. They weren’t the Garmin topographic maps, but they were small enough to download in an hour of computer time so they would have to do. As the name suggests, OpenStreetMaps are focused on street mapping for driver navigation, and wouldn’t be my first choice for up-to-date river mapping10.

Because all of this was happening in the 36 hours prior to the gear check, we’d had to consider what we’d need if I’d been unable to copy the maps. We’d discovered the corrupt micro-SD card in the late afternoon when the shops in Whitehorse were about to close, and we had no idea if the library would have a PC we could plug a USB cable into. Measured against the possibility of failing gear check, we’d decided to buy a replacement GPS. A quick internet search located one in stock at Canadian Tire in Whitehorse. So we bought a third GPS as a backstop to our data recovery plan.

Funny story. We bought the GPS from Canadian Tyre. In Canada. The description on the box said it comes pre-loaded with topographic maps. It would be reasonable to expect they would be Canadian topo maps, right? The sales assistant assured us they would be. What I didn’t expect when I opened the box and turned the GPS on for the first time was to find that it was loaded with topo maps of Alaska. Not the Yukon. Not other parts of Canada. Just Alaska.

The Alaskan maps finding had been staggeringly annoying at the time, but standing on a riverbank in Alaska with two GPSs now glitched13, I was relieved to be able to dig into the back of the boat and fish out that third GPS that contained the last surviving Alaskan topographic map. I held my breath as I powered it up. It worked!

Because I was steering, I took the fully functional GPS to the front seat and reconfigured Kate’s GPS to display the OpenStreetMaps which would provide at least a representation of the river around us. While she could no longer see the pink course line we were supposed to follow, she did have the hundreds of breadcrumb markers that I’d mapped out to indicate way points on viable channels. That would turn out to be very handy as we entered the braided floodplain of the flats.

In the dialect of Yukon 1000 competitors, “The Flats” refers to the extent of the Yukon River, which emerges from the hills and valleys south of Circle, to spill across the floodplain of The Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge.

After last year’s race, I shared some photos of The Flats with a work colleague. His response… “Desolate doesn’t do it justice, does it?”.

He was just back from a 3-week holiday at an exclusive resort in the Maldives. Looking at the crowd of tourists in his holiday photos gave me an uncomfortably crowded feeling.

The change in terrain as you enter The Flats is so stark that you don’t need a map to tell you that you’ve arrived. Over the course of an hour’s paddling, the flanking hills withdraw from the river’s edge, and the horizons of your world drop away. The change in scale is hard to explain. 10 km south of Circle, at the end of the valleys, the river is a ribbon of beige 1-1.5 km wide, with an occasional island bifurcating the never ending flow. In the 10 km of floodplain around Circle, the river forks 30-40 times. Five dominant channels emerge, each with roughly the same span as the single riverbed upstream. At the same time, dozens of streamlets and washouts interlace the mid-channel islands and bars, teasing paddlers with the chance of a shortcut, if they accept the risk of running aground.

It’s a liquid maze.

It had taken us slightly over four hours to get to Circle, by which time we were nearly two hours into The Flats and the navigation was starting to get serious.

Our first encounter with The Flats in 2024 had been very confronting. We had been well prepared, and as I said, we’d been studying and refining our maps for almost five years. What knocked us off our game was the aspect that you don’t fully comprehend when you’re studying a map at the kitchen table 14,000 kilometres away – The scale of it. It’s staggeringly large. What looks like a channel on the map, now looks like a lake when you’re on the water in the middle of it.

Kate was a bit freaked out by the scale of The Flats, particularly when it seemed we were spending more energy going from side to side than making forward progress downstream. For me it was more frustration of thinking we were arsing around in meanders while other teams were overtaking us in the faster channels14.

One day, when I’ve finished this series of posts about the race, I might put aside some time to explain the evolution of our mapping and how it evolved from a line drawn in Google Maps back in 2018. It’s been a long evolution.

For now. I’ll explain enough about the topology of The Flats to tell the story.

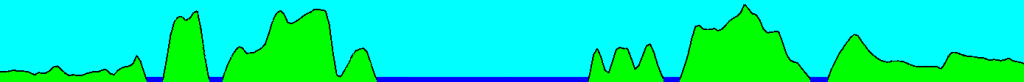

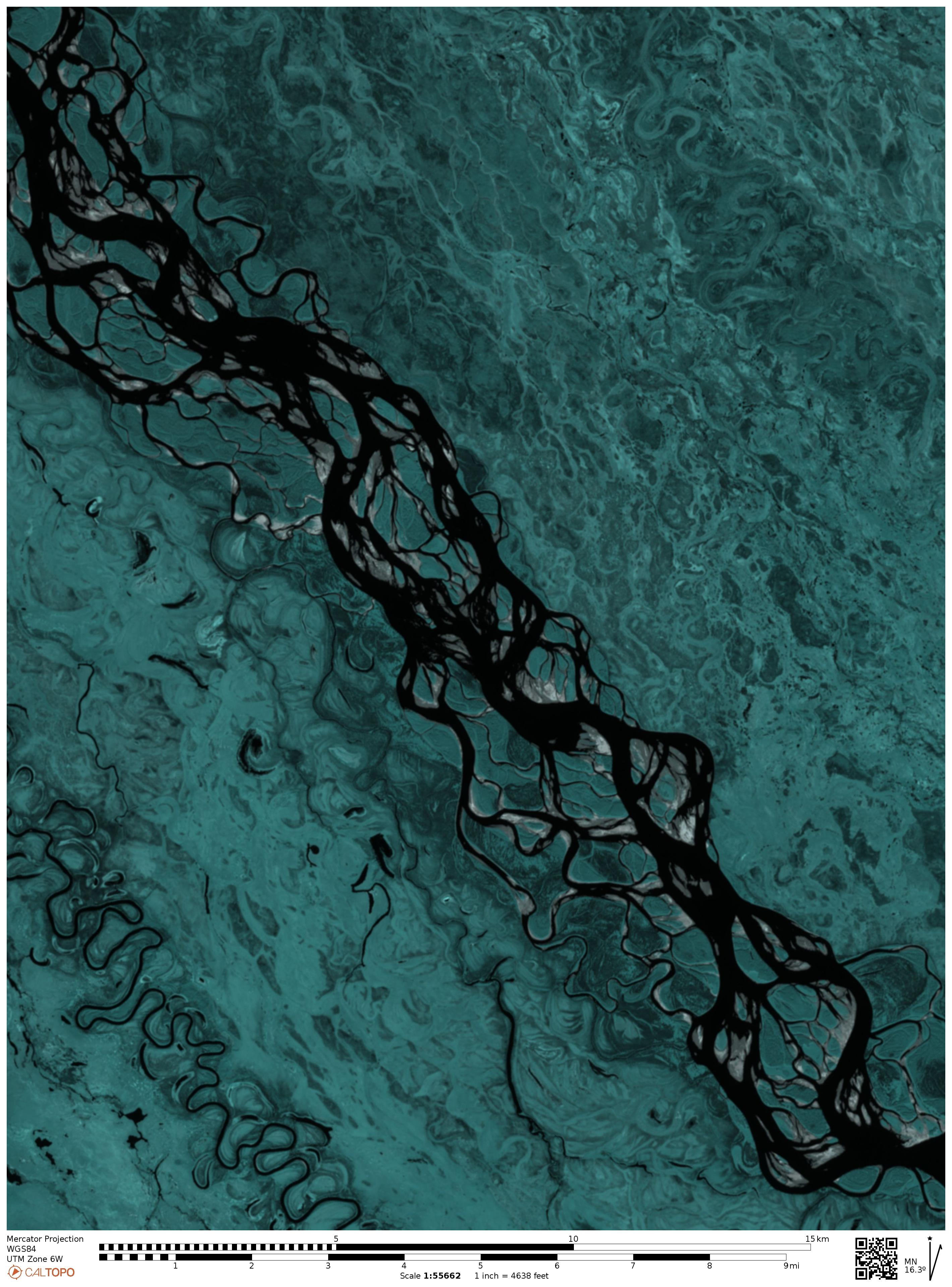

The picture bellow is a section of the flats captured by a satellite using Lidar15. The white channels on the right side of the image are the major navigable river channels. The lighter paths to the left are wetland streambeds which are wet but not presently navigable. When you look at this image, the intuitive way to map a route is by choosing the broadest channel. That strategy certainly works from Carmacks to Eagle. But now we’re looking at braided riverbed and wide no longer equates to deep. 2024 we found ourselves traversing an expanse of water 5 km across but less than a foot deep. We scraped the rudder for almost an hour before finding deep water again.

Hint: Look at the banks, not the water. Steep or undercut banks are created by fast-moving water16. Conversely, slower water deposits sediment.

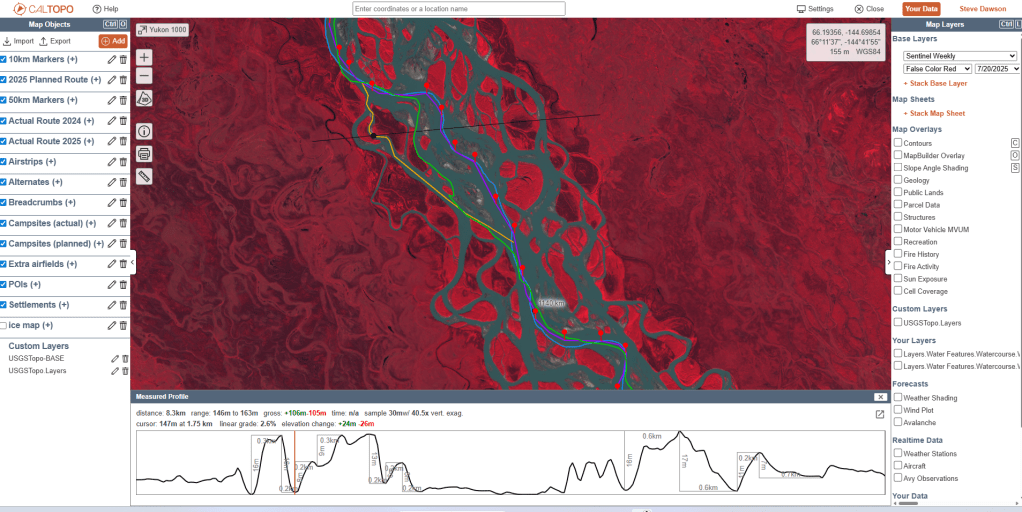

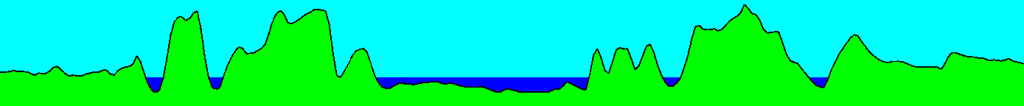

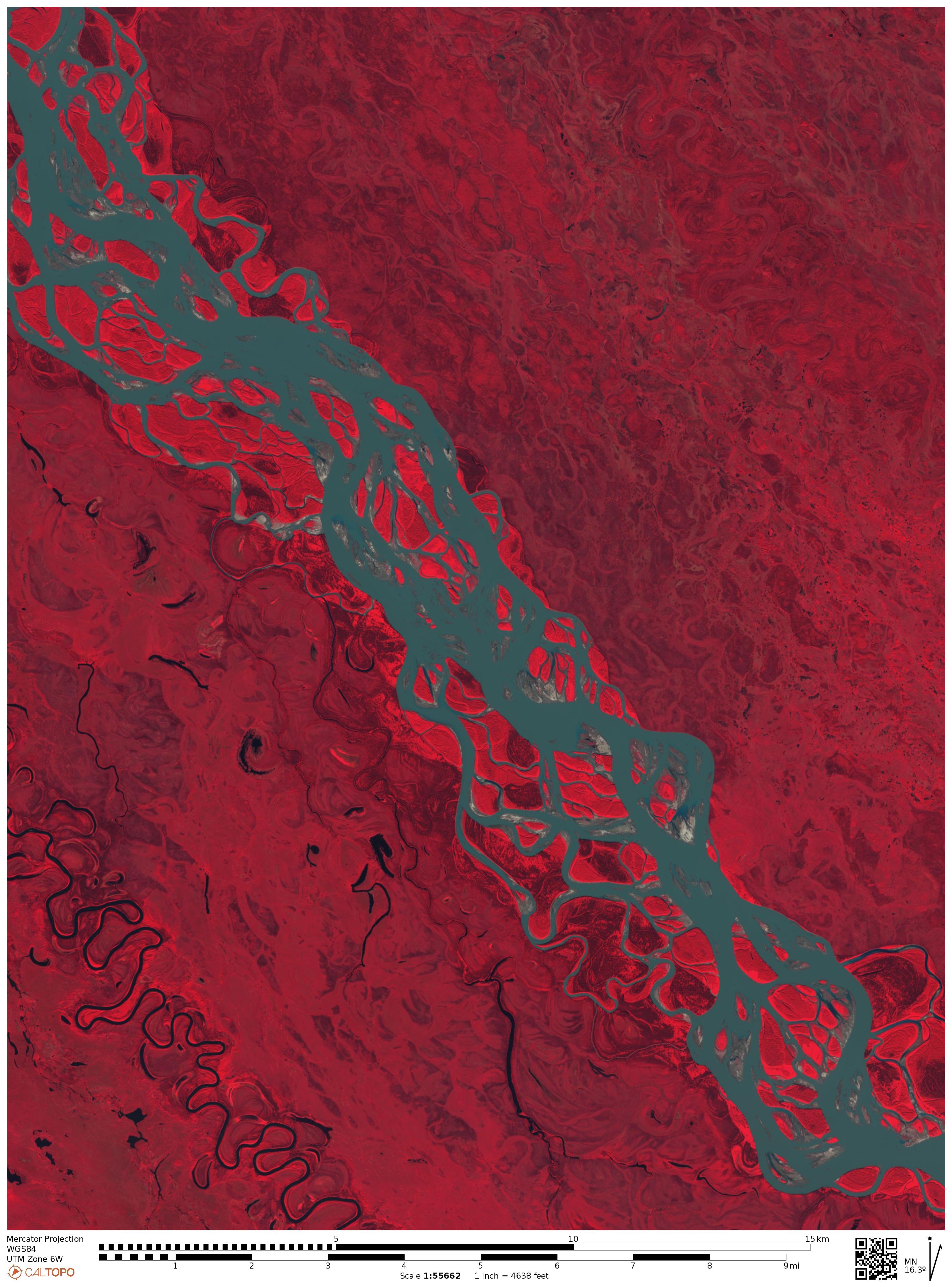

Now look at a similar section of the river in a mapping app called CalTopo. This is the Sentinel satellite imagery with false colouring, which is provided to help identify different types of vegetation. However, it conveniently increases the contrast of the water, which is the only part we’re interested in, because I’m not planning on bashing my way through the vegetation. One of the cool features of CalTopo is that you can get it to produce a contour profile. Normally, you’d use that to tell you the contour of the ridge you were planning to climb, but thanks to layers of mapping and imagery that can see through water, this can actually show us the contour of the riverbed, under the water. The contour profile at the bottom of the screenshot shows (with exaggerated scale) the riverbed cross-section where the thin black line crosses the river in the top 1/4 of the satellite image.

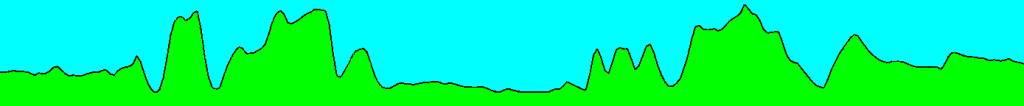

Here’s that same riverbed profile extracted and colourised.

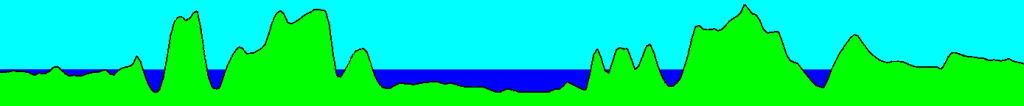

Now, let’s add some water, and instantly you can see how the channels lie in the low points of the cross section.

Notice how the water depth varies from left to right. The puddles on the extreme right are probably not navigable. The next two channels might be narrow, but they’re also deep. Their relatively steep banks likely indicate they are fast flowing too. The broad middle channel is carrying the bulk of the water but note the uneven contour of beneath the water. The final two channels on the right are again narrow, deep and probably fast flowing.

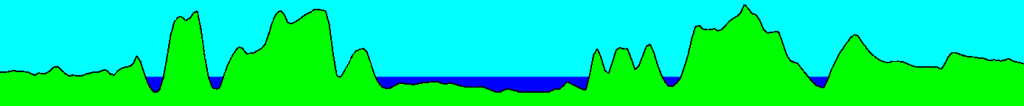

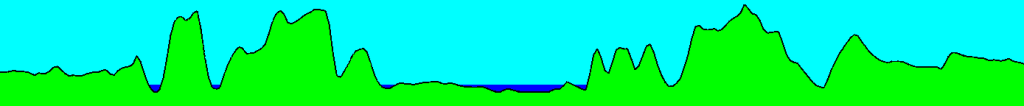

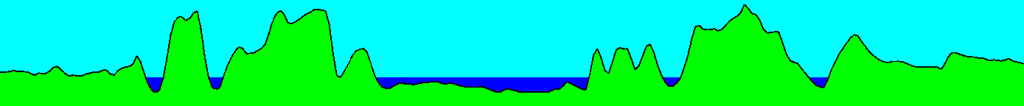

Now take away some water by dropping the water level. The shallows on the extreme left are gone, and while the left and right stream pairs persist, there is trouble just below the surface of the middle channel.

Now imagine that the topographic maps were drawn when the water was at that level. Then consider that when you’re using topographic mapping, you can’t see the underwater contours17. So what you see is this…

Take away a little more water, because less snow fell upcountry, the ice breakup came a little earlier and the water level has been steadily dropping since then. The middle expanse is now even shallower and there are a couple of underwater rises which might now be shallow enough to cause you problems.

But the topo map will still look the same.

Obviously, it would be incredibly time-consuming to map the river through a series of cross sections18, even if you only did it for the 130 km of The Flats. Assuming you did the riverbed is seasonally dynamic, and even a medium-sized rain event upcountry could be enough to rearrange sand bars in the broad channels. But not so dramatically in the narrow channels…

Still, understanding the nature of the underwater contours can help you predict the relationship between landforms and the reliable flows to navigate the maze.

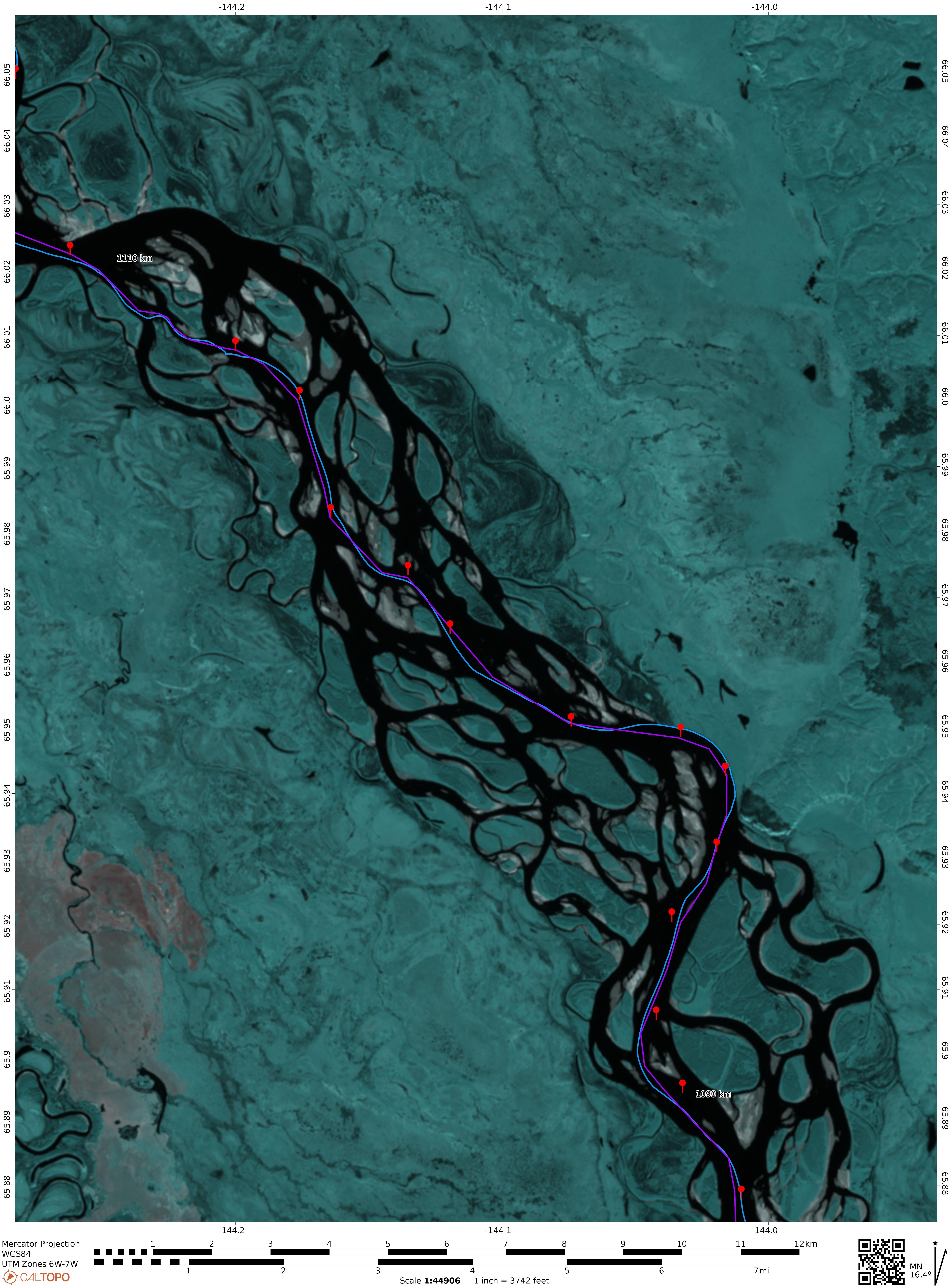

The other tool is satellite imagery, and with apps like CalTopo you can access satellite imagery that is updated every week. Our printed map books while predominantly topographic, included detailed satellite imagery for The Flats taken less than two weeks before we paddled past Circle. We’d updated our precise route from Whitehorse to Lake Laberge based on last minute imagery that showed a landslide that had choked the river and a shortcut to the start of Laberge that had dried out since we plotted the course.

Satellite imagery is a mixed bag. The part of the Yukon River we are paddling runs 1600 kilometres across 5 or 6 significant terrains, each attracting different weather patterns. For any given date, maybe a third of the river will be obscured by cloud, sometimes for weeks on end. From October to April, the whole place is white with snow or ice and the river becomes indistinguishable from its surrounding terrain.

But the satellite I was accessing crosses the Yukon River every 2-3 days, so if you’re prepared to spend the time scrolling along the river and then flicking through the satellite dates to find the best imagery19, you can get a really good set of images for the entire distance.

Fortunately, from June to July, the skies over The Flats are clear more often than not, allowing recent coverage of the river from Circle to Fort Yukon. And because the rest of the river has pretty stable topology, you don’t really need up-to-the-minute satellite images of Laberge or Five Finger.

While I was scanning backwards and forwards through satellite passes looking for cloud-free images I developed a theory. The best satellite images to have are obviously the most recent you can manage given the logistics of having to produce two complete sets of waterproof maps and bind them up in some fashion. The best images are for dates after the whole river has melted and all the surrounding snow and ice has gone. If you can wait until the ice melt floods have cleared, the river will probably have stabilise for the season and the dates of the race (probably).

Hint: You can develop maps using a lot of different websites and services. After 5 years of planning, I’ve landed on caltopo.com; linking in a layer of topographic info from USGS because it’s the clearest mapping with the best contrast for printing. I then print them through an office printer onto waterproof polymer paper and spiral bind them.

But what if you go to earlier images, before all the channels have melted?

A good question might be, which channel melted first?

According to a couple of research papers, the first channel to thaw “might be” determined by a combination of subsurface water movement, with friction causing warmth. That movement displaces near-freezing water from beneath the surface ice, causing a cascade of melting and flow and warming and melting. The first channel to open may be due to being deeper than its neighbours.

It’s a paper-thin theory, but when I compared the first channels to open up with the best-choice routes using other methods, they correlated quite strongly. Some were inevitably scoured out by flooding, but it seems like a viable way to identify the thalweg from satellite mapping over time.

Hint: If you’re considering entering the race, Google THALWEG. You’re welcome.

There’s another technique to identify faster, deeper channels based on the shape of the midstream gravel bars. How much they look like a teardrop indicates how fast the water is flowing past them. That’s based on some work by a German hydromorphologist who spent a season wading around the Yukon flats with a long pole measuring riverbed contours20. At its simplest, fast water carries sediment further than slow water.

Despite having done the work to identify the deepest channels, sometimes deep channels feed into shallow confluences, so in addition to identifying the deeper, faster channels, you also need to string a succession of short 1-5 km sections into a sequence that keeps you predominantly in the deepest water for as much of the 130 km as you can manage.

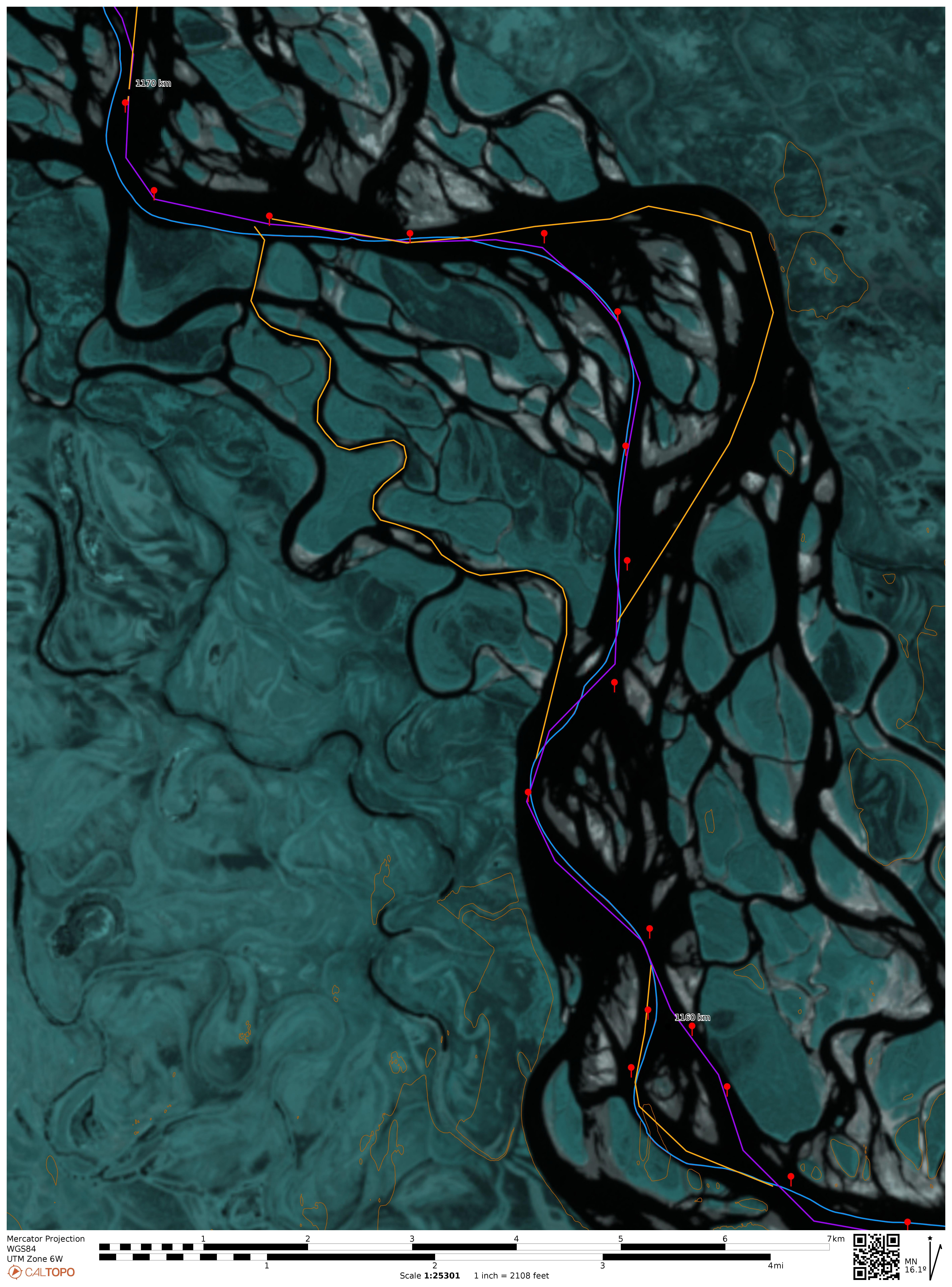

We spent hundreds of hours developing and refining our planned course through The Flats, including dozens of alternate channels that would still be viable if we got diverted off our preferred course by a log jam or shoal that appeared when the water level dropped.

Our final mapping, both in GPS and in our printed map books, shows as plaited ribbons of intersecting courses, colour-coded according to whether they were primary, secondary, tertiary, or in two places downright reckless. The reckless ones were coded black and included only because, if the river level allowed them, there was the potential to shave kilometres off the distance. We’d have to assess those on the ground, on the day, based on how much water, if any, was flowing into them when we got close.

There’s a saying… “The harder I work, the luckier I get”. Our hard work was going to make us lucky this day.

The wind was already howling across the water as we entered The Flats proper. With open plains to the east and west, the westerly wind blew unimpeded across the land and was whipping up small waves across the river channels.

During the briefing, Jon had offered some advice on navigating the flats, which boiled down to “The river flows towards the sea, follow the current”.21 The challenge in these windy conditions was that the wind and waves were obliterating any signs of current that we might have seen on the surface of the water.

Normally, we don’t refer to our paper maps. They’re a race requirement, but our primary navigation tools are GPS, visual navigation, river reading, and a table of times and distances that sits under our deck bungees22. Stowed in the deck bags, we have a set of 1:500K topographic maps. They’re roughly 160 kilometres (100 miles) to a page, so ten pages, separately bound from the rest of the maps. We use them when we’re checking gross progress along the course. They’re no help for navigating around islands or selecting channels because most islands vanish at that scale23.

Stowed in waterproof cases (x2), we have 1:50K topographic maps, which are sufficient for navigation24. That’s 50 pages of mapping, or about 30 kilometres to a page. At the back of that map book, we have our high-resolution, false coloured satellite maps, overlaid with the same routes and markers as the GPS and topographic maps. Seven pages of satellite maps running from Circle to Fort Yukon.

These were the heart of our navigation strategy for The Flats.

We’d printed our satellite mapping a few days before leaving home, aiming to get the most up-to-date view of bars, shoals, and channels that might have been laid down by recent floods. When we hit Circle, our imagery was still less than two weeks old. There was always a chance that flooding driven by heavy rain might change the course of the river, but at some point, you have to print out the best version you can find and deal with the variations when you get to them.

If the river level changed significantly, we would need to mentally adjust the mapping we had to the conditions in front of us. Add a metre of water and we’d expect to be paddling over most of the shoals. Only the major islands with vegetation would still be relevant. Drop half a metre and the on-the-fly adjustment becomes much more complicated as you try to predict which channels have now dried to a trickle and threaten to bottom out.

What we were paddling into was the Goldilocks combination of mapping and river levels. Our two week old imaging had been captured at a low water period, where the bars and shoals had been clearly exposed to the satellite. Then the water had risen slightly, no more that 0.25 metre, barely submerging those contours.

Our satellite mapping, because of luck more than anything else, now showed us where the shoals lurked just below the surface. With the wind driving a chaos of waves across the surface of the water, we had the golden ticket to avoiding the un-seeable shallows.

We were simultaneously referencing paper maps for landmarks, and GPS for bearing, We synchronised the two methods using the hundreds of breadcrumb markers that were recorded in both formats. We zigged and zagged betwixt the hundreds of breadcrumb waypoint. Unlike our previous floundering run through The Flats, this course was aggressively positive. We’d paddle 600 metres, turn 30 degrees right, advance another 400 metres and turn back 90 degrees.

An external observer would think we were blind, drunk, or blind drunk. Picture a blind man navigating a room after the familiar furniture had been removed, or a minesweeper navigating a clear path through a mine field. That was us.

Hesitant at first, because a perfect course seemed too good to be true, we quickly leaned into our success and increased our pace. Confirmation of the submerged hazards came regularly in the form of branches and logs that were stationary in the flow. They were static because they were hooked up on shoals barely covered with water. The dozens of alternate distant channels could be ignored because the only channel we needed was directly in front of us. The overwhelming scale of The Flats wasn’t overwhelming anymore because it was no longer relevant.

Our world was a path 1000 metres in front of us and 50 metres either side.

To explain, let’s go back to the cross sections for a moment. Our satellite mapping was based on water levels from two weeks earlier.

In the intervening two weeks, the river had risen by just a few feet, enough to hide the shoals, but not enough to paddle over them.

And this is where we got lucky, rather than invalidating our maps, the changing river level turned our landscape of shoals and bars into an accurate map of the submerged hazards that now lay just below the surface.

For the next eleven hours, we made hundreds of inexplicable turns at speed, consistently ignoring the shortest routes between islands, knowing that we were skirting unseen subsurface hazards.

The further we traveled without encountering shoals, the more confident we became in the accuracy of our mapping. That confidence was invigorating and wiped any thought of better routes from our minds. We were on a good path. It might not be the best path, but it was working for us. Only the leaderboard would tell if it was a better path than any other.

For 130 kilometres, the only thing that slowed us down was a brief problem with our compass bearing.

The wind had spun up to a full-on Gale with a capital G. At one point, we saw a couple of mini-tornadoes dancing around on the western shore.

Reaching another of our never-ending waypoints, we made a planned 30 degree turn to the left, aiming the GPS at the next waypoint, almost a kilometre ahead. As we came out of the turn, the distant waypoint remained belligerently to the left of our bearing. We turned further to the left. The GPS showed we’d turned a total of 20 degrees, but it felt like 45. Still, the waypoint remained disturbingly left of our bow.

Remember, we are trying to aim the bow of our kayak at an imaginary marker that only exists on the GPS screen sitting at the front of my cockpit. I’m looking down at the GPS watching a virtual X marks the spot on a wide expanse of featureless water. Still trying to point the bow at the marker I could see on the electronic screen, I momentarily lifted my eyes to the horizon, trying to pick out a reference point in the distance.

A confounding factor in the flats is the islands that aren’t on the map or don’t look like the island on the map due to erosion or the approach angle. Often, two or more islands with a separating channel would appear to be a single island until you could look directly through the channel.

We’ve spent a lot of time on the water estimating distances without reference to landmarks like people, houses or trees. With those familiar references, you can guess that a coloured dot on the water is a kayak or canoe, and they’re 1-2 kilometres away. If you can see their head, they’re 250 metres out. If you can see their smile, you’re about 50 metres out.

With no easily scaled references, and only trees that you know are stunted, it is quite difficult to judge distances across the water. Focused as we were on the paper maps and digital markers, we weren’t paying attention to our wider surroundings.

Normally, we’re happy to paddle in silence for long periods of time, but we’d been constantly chattering navigation references backwards and forwards since entering The Flats. Kate was co-piloting from the back seat, calling out reference points and confirming the turn directions to the successive markers. She was focused on the paper map, I was looking at the GPS. We both had a sense that something was wrong.

Kate called it before I did. She noticed that the current was running across our path when we should have been running with it. I’d just twigged that two landmarks I’d spotted, one near and one distant, were moving apart, even though we should be padding straight at them. A navigation lesson from high school technical drawing class stirred in the back of my brain. If these two immovable landmarks were moving apart, it was because we were moving sideways.

The reason we couldn’t draw a bead on the next waypoint was that the combination of howling wind and a strong current was sweeping us sideways faster than we were moving forward, and our GPS, which uses position vectors rather than magnetic North to calculate bearing, was seeing our primary direction as sideways. We’d literally turned 180 degrees back upstream before we realised we were being misled by the electronics. We’d doubled down on the error by paddling head down with our eyes on the GPS and ignoring our surroundings25. We’d also been underestimating the strength of the wind and currents.

The simplest way to correct the bearing error was to pull out the compass I had stowed in my map case. Clipping it under the deck bungees, it was easy to compensate using the additional directional information26.

We needed to pay more attention to our surroundings, the land forms, the currents, and the channels.

We were in the middle of that “paying more attention to our surroundings” when we found ourselves skirting the outside of a long left hand bend. The fast current on the outside of the bend was gently pushing us towards an undercut soil bank topped with trees.

As we paddled past, we could see the current undercutting the bank. Small stones and lumps of dirt were falling into the water, making the margin of the water muddier than the main channel.

We were still “paying attention to our surroundings” when I started noticing large white boulders embedded in the soil. The obvious ones were the size of large sofas, poking out of the bank undercut by the sweeping current. They were quite precariously supporting the soil and trees above like a cantilever beam.

My first thought was large blocks of quartz, until I noticed they were melting. We could see water dripping off them. In a few spots, we could see voids in the soil where one of the ice blocks had melted out completely.

We suddenly felt very unsafe, paddling as we were, along the edge of an overhang, topped with trees, supported by melting blocks of ice. If one of those blocks collapsed, we would be well inside the sweep of trees and soil that would crash into the river. We quickly moved 30 metres out from the bank.

When I got home, I Googled the blocks of ice. According to the research papers I read, the ice blocks are likely to be glacial ice trapped beneath an insulating layer of soil since the last period of glaciation. As temperatures rise in the region, the soil which has previously been permanently frozen is now starting to melt. What we could see at the rivers edge was the rapid erosion and further melting of soil that was previous impervious to erosion in its frozen state. It seems to me like a system in collapse.

All of that brings us back to the end of the northward push and the sighting of the two person canoe 20 km south of Fort Yukon. We’d had a very good run through The Flats and it now seemed that we were about to catch one of the other teams.

The river swept right around a expansive apron of scrub covered ground on the left hand bank. We’d closed to about 500 metres on the canoe and could see they were planning to run one of the narrow washouts that laced the apron. Judging our speed advantage against what we could see on our satellite maps, we made a tactical decision to stay in the larger channel and take the long way around on the right. We’d travel maybe a kilometre further, but there would be no risk of running out of water.

Hint: Beware of other peoples routes. Our planned route is something we hold close, like most other teams. There are plenty of places where you might be able to access a teams actual route – on Garmin or Strava for instance – but invariably you’ll find that following that route will include oddities like the sheltered creek we used to get some respite from the wind or the detour we made to get to the gravel bar so I could have a poo. Unless you’re planning to erect a monument with a brass plaque to commemorate that moment in history, you don’t want to follow our track.

We had a strong sense from the way the canoe was moving that they were probably looking for shelter rather than taking a shorter path through the corner.

We lifted our pace to compensate for the longer route and hoped that we’d surprise the canoe when they emerged out of the shrubbery into the main flow. We never saw them emerge and it was us that got the surprise.

Just as we reached the apex of the bend, we spotted a couple of hi-viz jackets atop a double kayak, pulled up onto a sand bar. It was The Duckers. Our ability to time our arrival to their bathroom breaks was starting to get a little creepy. This wouldn’t be the last time.

We weren’t about to add distance to our rack by running wide of their spot on the sand bar, so we made a casual enquiry as to their general health as we passed within 20 metres of them.

We’d now caught two other teams. The emotional lift was huge.

The river consolidates back into large flows and the river banks start to rise as you make the final approach to Fort Yukon and the northern-most point of the race.

Fort Yukon is a small community sitting on the Eastern (right) bank of the river at the point where the Porcupine River joins the Yukon from the North East. There’s no reason to pass close to the settlement27. The river veers sharply west and phases into a new character.

For the rest of day 6 and day 7, we’d be paddling a weave of broad channels between large islands with tall banks. The best route is largely obvious. Mistakes are still possible. Most would cause minor delays, however there are a number of places where choosing the wrong channel will send you spinning off into an oxbow for 3-4 hours before returning you to the flow again.

With the complexity of navigating The Flats behind us, we relaxed…

… just a little too soon as it turned out.

We were about 5 km past Fort Yukon and approaching the first of the islands. It was around 8:30 pm so we had around two hours of paddling still ahead of us and my attention was on our map which was showing we were approaching an island we’d camped on the previous year. That island was now just in front of us and after several days of making only slight improvements over our previous race, it was looking like we’d make a big jump this night.

Again, Kate called it moments before I saw it. Shallows. The water in front of us was rippling, distinct from the wind blown waves across the rest of the river. The ripples were a sure sign of gravel just beneath the surface.

After a flawless run through the most complicated section of the river, we ran around on one of the easiest.

Lalochezia is the rare use of foul, vulgar, or indecent language to find emotional relief from stress, pain, or anger. This phenomenon, sometimes called “cathartic swearing,” allows for a discharge of stress, which can lead to a feeling of being better or a temporary reduction in pain tolerance. Studies suggest that swearing can lower the stress hormone cortisol and increase levels of serotonin, contributing to this therapeutic effect.

The studies are wrong.

My cathartic discharge of stress and lowering of cortisoles was negated by the sudden appearance of The Boys in their canoe. Somewhere in The Flats, we’d passed them as well without being aware of them at all. Now they were passing us as we wobbled the boat on the submerged swathe of gravel, trying to get loose by allowing a cushion of water to build up under the boat. The Boys were a hundred metres past us before I abandoned malevolent glaring and conceded to climbing out of the boat to drag it off the gravel and into deeper water.

With our buzz completely shattered, we settled back into a solid pace, keeping The Boys in sight, but not closing on them. Our energy levels starting to drop and the rain starting to fall we’d settle for not being caught by the mystery canoe or The Duckers who wouldn’t be far behind us still.

The temperature dropped rapidly as rain, wind chill, and whatever the sun was doing combined to sap our body heat.

We managed to push through to almost 11 pm, determined to hold the placing we’d gained back throughout a mostly successful day.

Rounding a left hand bend, we decided the silt covered embankment on the southern riverbank was probably the best we’d get for the night. There was an open spot in a clearing of low bushes that would offer some shelter from the wind while still giving us space to see any bear emerging from the vegetation.

We were both desperately cold. I was shaking uncontrollably to the point where I was having difficulty inserting the sections of the tent poles into each other. All I wanted to do was get into dry clothes and into my sleeping bag to recover some body heat.

Our tent had now been continuously wet for days on end. It had gone away wet in the morning and every part of it was soaking wet. When we unzipped the doors and peered inside, we could see water puddled on the floor. We were both too cold to be interested in fetching a sponge from the boat. We shook the water off our foam mats, threw them into the tent on top of the puddles and laid the sleeping bags on top. Kate’s sleeping bag was now wet through at the foot, probably from hanging off the mat the previous night. Mine was damp on the outer shell, but didn’t seem to be wet through. This is why we carry synthetic fill sleeping bags. They’re just as effective when they’re wet. We slipped into our merino sleep layers and slid down into our bags to warm up. It was then that I discovered my inflatable pillow – really the only luxury item we carried – had already gone flat.

Another episode of Lalochezia erupted. After a moments consideration, I decided against making a dash through the rain to the boat to find a dry bag and a fleece jacket to substitute for my punctuated pillow. Shoving two pairs of socks and a pair of merino undies into a dry bags, I fashioned an utterly useless pillow and surrendered to sleep.

Overall we’d had a very successful day and the most intimidating part of the race was behind us. We’d been ignoring wrists and abrasions for most of the day, preoccupied as we were with the complexities of navigation. We’d made three places and lost one again to end up 14 kilometres closer to Dalton than we had been on day 6 the previous year.

| End Time | 15/07/2025 22:58:31 |

| End Location: | 66°35’42.6120″N 145°48’51.4800″W |

| Altitude: | 128.0 m |

| Distance: | 200 km |

| Paddling Time: | 17:13:42 |

| Non-moving time: | 00:23:52 |

| Average Speed: | 11.6 kph |

| Max Speed: | 17 kph |

| Race Position: | 7th (up 2) |

Help encourage more posts by buying Steve a coffee…

Choose a small medium or large coffee (Stripe takes 10% and 1% goes to carbon reduction)

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Donate- After Carmacks on day 2, the sun no longer sets. It dips down to the horizon but never completely disappears. As you move further north, the descent is less and less. Above the Arctic Circle, it merely kisses the horizon. Not that we could tell, due to the persistent cloud. ↩︎

- “currently” because the Arctic Circle is presently moving north at a rate of 14.5m (80ft) per year. ↩︎

- Does anybody else feel disappointed to be living on a planet that wobbles around the sun like a supermarket shopping trolley? ↩︎

- We’d find out later that some racers had gone to cover in their tent due to the lightning. I can’t say I blame them. ↩︎

- To this day, I’ve got no idea why they vanished. Maybe the time zone change, maybe the longer day and the track archiving wrong. ↩︎

- Each team is required to carry two GPS units. A primary and a backup. I’m not certain, but I suspect all teams run them both for the duration rather than having their backup in a drybag in the boat. ↩︎

- Lights are no use when the riverbank is a kilometre away. You could follow the left or right bank, but that’s guaranteed to turn a 111km race into a 160km adventure. ↩︎

- 2016, several paddlers were using a GPS plot I’d put together in 2014. I’ve consistently shared my latest-but-one GPS track with other racers. After the 2015 race, I’d updated the track in one spot to avoid a tree that had fallen into the river with one branch poking up out of the water, right on my track. The version I shared didn’t have the correction. The tree had continued growing in the water, along with the branch, which was reported hit by at least 6 boats using my old track. That gives you an idea of how accurate a GPS is. ↩︎

- Having the airfields loaded into your GPS is a safety requirement, which may be checked pre-race. Not having them loaded on our GPS was not an option. The one upside to this was that I went online to verify the airfields list and discovered that since the 2024 race, Jon had added 6 new airfields that I hadn’t previously noticed. ↩︎

- Having the best map is a bit like having the tallest of the Seven Dwarfs. All drawn maps of the Yukon Territory and Alaska are out of date and inaccurate, especially in geographically volatile areas like The Flats. The OSM maps are relatively up to date, but their river boundaries lack fine detail. ↩︎

- We had a problem with footrests in one boat and improvised footrests using salad tongs and zip-ties. The heavy boat bent the hinges on our pedal steering while we were training on the lake, so we swapped them for door hinges from Home Depot. A spray deck that didn’t fit the boat, replaced from what was available in Whitehorse. Others have had different problems. A friend arrived to find their legs were too long for the boat they’d rented (and the rest of the rental fleet). They bought a boat from Kanoe People to stay in the race. Mark and Julie from Bristol Train had their meals confiscated by Canadian customs because they contained meat. In the scheme of an event that has cost $$$,$$$ to enter, a $350 GPS is no big deal. ↩︎

- 2019 Texas Water Safari, we were part of the team that quite famously snapped a 35ft 4-person canoe in half during our training run a week before the race. We spent a week working on rejoining the two halves of the boat and finished 17th. ↩︎

- I have a friend who is a retired risk management executive from a major bank. His oft-repeated advice is “never put your faith in anything that floats, flies, fruits, ferments, fucks, or takes batteries”. This translates to shipping, airlines, orchards, vineyards, race horses (or marriage?), and mobile phone companies. Words to live by. ↩︎

- They weren’t overtaking us. At least not because we were on slow channels. Everybody has the same experience in The Flats. Our 2025 plan was very similar to our 2024 plan, but it was 1000% better mentally because we were convinced it was right (or good enough for government work, as the saying goes). ↩︎

- Lidar is basically radar with a laser. Lidar can be used to produce an accurate 3D map of a surface. ↩︎

- To detect steep banks on satellite imagery, look for dense vegetation that stops suddenly at the water’s edge. That often indicates an eroded bank. A transition from vegetation to gravel to water is the opposite. ↩︎

- Topology is land mapping. The mapping of sea beds and river beds is called Bathymetry, and there ain’t none of that where you’re going. ↩︎

- It was. ↩︎

- I was. ↩︎

- The fact that his research was based on wading around the river is another indication that The Flats could also be called The Shallows. ↩︎

- This ranks up there with “It won’t get better if you pick at it” and “It will stop raining or be dark by midnight” (obviously this is wisdom from further south) ↩︎

- One practical reason why we don’t rely on paper maps, aside from the fumbling with wet pages (even waterproof pages are a nuisance because they stick together when they’re wet), I need reading glasses to read small print. I can’t paddle with reading glasses on, so our navigation is aligned to what we can read without needing glasses. ↩︎

- An adjacent problem is that I can’t read a map without my reading glasses and I can’t see past the end of the boat if I’m wearing those glasses, so I don’t use either the maps or the glasses, normally. ↩︎

- We had attempted, as an exercise only, to use paper maps to better navigate from Dawson to Eagle in 2024 and found that our scales were woefully unsuitable. We’d printed them out with too much detail, making it almost impossible to pick significant landmarks. Because the map pages didn’t have enough context, it was nearly impossible to tell (without GPS position) whether we were on page 26 or page 27, or 28. Once you get out onto The Flats, there are no landmarks, the terrain is effectively flat to the horizon and as a paddler, you are sitting in a depression below the level of the terrain. You quickly understand how a rat feels in a maze. Unless you can get a position fix, maps are again of limited use. ↩︎

- In our defense, there aren’t a lot of distinctive reference points in said surroundings. Turn full circle and all you’d see is short pine trees, water, gravel, and repeat until you’re dizzy. Turn around six times and you’ll be hard pressed to tell upstream from downstream unless you check the wind direction. ↩︎

- An interesting point when you’re using a compass at these latitudes, the longitude lines are visibly converging because you’re getting closer to the North Pole. The map and compass navigation I was taught in high school back in New Zealand never covered how to take a bearing when your map grid is no longer square. ↩︎

- Things I think I know about Fort Yukon. There’s an airfield, if you need an evacuation. It’s the only community which allows alcohol in the region which attracts a sort of rowdiness that is best avoided. Travelers are advised to seek accommodation rather than camping out within walking distance of the settlement. ↩︎

2 thoughts on “2025 Yukon 1000 – Day 6 – Tuesday”