Downhill – Stevens Village – Meeting the Kiwis – Jokinaugh Island – 77km from Dalton

| Start Time: | 16/07/2025 05:42:14 |

| Location: | 66°35’42.6120″N 145°48’51.4800″W |

| Rest Time: | 06:43:43 |

We’d had a poor nights sleep between going to sleep shiveringly cold, having a puddle of water dribbling around the floor of the tent, and spending the night on a makeshift pillow fashioned from a drybag, some socks, and a spare pair of undies. It didn’t make for a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed start to the day. The Duckers and another kayak team paddled past us as we were pushing away from the shore. Pushing into the current we followed them downriver.

From Fort Yukon at the northern extreme of the river to Stevens Village, the river runs as a series of large intertwining major channels. For the most part there is one dominant channel, and two to three alternates which stay within 5 km of an imaginary centreline of the river. Compared to The Flats from the previous day, these channels are all good for navigation, some being gooder than others.

At the outer margins there are side channels which loop away from the mains, carousing through the flat lands before returning to the main flow. If you wander into one of these loops, you could find yourself paddling an additional 20 kilometres just to advance 5 kilometres downriver. These divergent channels are not good. Paradoxically, some of them flow faster than the main flows, so there is a danger of being drawn into them if you approached too close.

Perhaps still a little complacent from our perceived success on The Flats the previous day, our first mistake was exactly that. It was early morning and we were briefly paused for one of our hourly fuel in and waste out breaks.

Hint: The opening on your pee bottle cannot be too smooth.

We were in a river channel to the right of centre due to make take an upcoming left branch which would take us back towards the middle of the river system. While we ate, our boat was being swept quite quickly along a beach to our left towards the mouth of the left channel. The river was flowing quickly giving us the opportunity to have a stretch and shake off some aches without actually coming to a complete stop.

Relaxed, and not paying enough attention, we didn’t notice until too late that we were sliding right, away from the opening almost as quickly as we were moving downstream. The opening we’d planned to take wasn’t where the current was going. Because we’d been intent on taking the left channel, we hadn’t given sufficient thought to where the right channel might go. Quickly zooming the GPS out, we realised that the channel we now recognised as the main flow was one of the dreaded wanderers. We tried in vain to turn into the current and fight our way back to the mouth of the left channel before conceding defeat and surrendering to the consequences of our error.

We’d missed the shortcut and we’d now suffer an hour as penance. We were lucky it was only a short loop. Some are massive.

Although it wasn’t a massive loop, it did have some additional problems in store for us. Being one of the branches we had no intention of taking, we’d given it no thought in our preparation. We’d specifically never considered how to get back out of it and back to the main channels as efficiently as possible.

Some loops start cleanly and run a well defined path until they rejoin the main flow a short unproductive distance downstream. In this case, the clean entrance looped around but rejoined through the delta of another river entering the Yukon. The channel we were on would soon (in about an hour) crash into the side of a series of branches and streamlets. We’d have to make an on the fly decision about which one to turn into, hoping it would bring us back to the main.

We ran aground twice on gravel bars before we finally made our escape. We’d be more on our toes for the rest of the day.

Looking back it was a weird day. I took two photos of the landscape and after six days of recording random thoughts on video, on day 7 I had nothing to say.

It wasn’t that we paddled in complete silence. We were constantly exchanging information about routes, times, and upcoming breaks, but there was little conversation. Kate made several concerted attempts to engage me in conversation, but my heart wasn’t in it this day. My replies were short and perfunctory at best. I wasn’t in a bad mood as such. Looking back, I think I was just wrung out from 6 previous days and my reservoir dam of conversation was empty.

A few hours further downriver we had another minor detour when we misread our maps and turned into a wide opening which proved to be a small dead end on the map. The correct opening was 5 times larger and just around the end of an island we couldn’t yet see past. It only cost us a few minutes, but it indicated we were both getting tired and mistakes were mounting.

Some time around midday we came across the Duckers again. Again they were out of the boat. They were a few hundred metres into a left branch we had no intention of taking, so this time they could have their privacy.

Our third navigational scale error of the day was as we lined up a short cut at Victor Slough. On the map the oxbow hangs down like an uvula from the centreline of the river. It’s 9 kilometres to follow the main flow around the bend. The slough cuts across the neck of the dangler in a zigzagging 5 kilometer path, shaving 4 kilometres off. At our average speed, that’s about a 20 minute time saving.

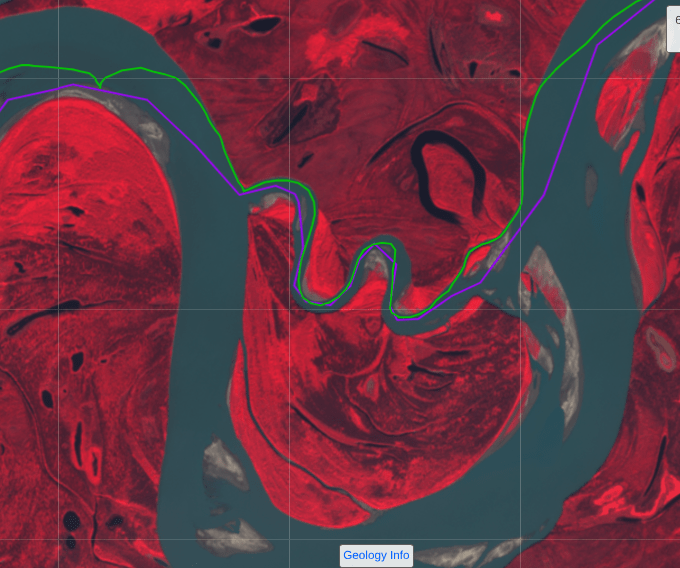

In this case our error wasn’t huge, and in retrospect probably added a little excitement which was much needed at the time. The purple line on the map above is the planned track. Our actual track was the green line. We were moving from right to left, heading west downriver.

The inexplicable part is why we took a narrow channel into the slough when there was much bigger unobstructed entrance to the main channels only 300 metres further along. My memory is that we though that was part of the main bend, but that’s 3000 metres further round. Scale again.

The result was we squeezed our 22ft double sea kayak into a fast moving narrow creek-like cut, dodged fallen logs and threaded the needle between gravel bars and undercut banks to come out 500 metres later in the channel we should have taken in the first place. As we’d bashed our way through the creek like a steel drummer in a reggae band, we’d agreed that anybody who followed us in a boat with less substantial rudder fittings was probably engaging more in ricochet ballistics than steering1.

Emerging from the creek, and waving off the party of mosquitoes we’d crashed through, I recognised the channel in front of me and realised we had taken a shortcut into a shortcut. Deja Vu from last year. We were only 1/5 of the way across the neck of the oxbow. Still it was fun.

We were on the second zag of the shortcut when we heard the helicopter… It was approaching from downstream and seemed to be flying quite low, maybe 100-150 feet. We could see a crew member observer looking out the open side door. They circled around us twice as we paddled through the cut, then continued upstream.

My first thought was that it was a local news crew looking for some television footage of the 1000. But they had no obvious camera equipment. The livery of the aircraft was unfamiliar to us, and being almost directly overhead, we didn’t have a clear view of the markings on the side. But the crew might have been wearing uniforms with law enforcement styling. The words STATE TROOPER flashed through my head.

I’m not spiderman, but I have developed one very specific spidey-sense during my years recreating in the wilderness with accompanying electronics. In this case my spidey-senses were saying that our emergency contacts were probably on the phone to the search and rescue center in Canberra telling them that the alert they were getting as most likely a false alarm and if we were moving we were unlikely to be in need of assistance.

We’ve been here before…

Our first Search and Rescue (SAR) activation happened in the early hours of the Yukon River Quest in 2019. We were 2/3rds of the way down Lake Laberge on a fairly kinetic day2 when a powerboat approached us from behind and asked if we were in distress. Everybody on the lake that day was in some degree of distress, which coloured our initial response until they told us that we’d activated the distress beacon on our SPOT tracker. The tracker was in a waterproof Pelican case strapped to the tail of our boat. It was well beyond our reach so we hadn’t activated it, but when we pulled up on the nearest beach we found that it was indeed transmitting an SOS. Water had somehow penetrated the case3 causing the SOS button to fire4. We reset the beacon and moved it to the cockpit cover just in front of me to keep a eye on it. It activated five more times in the next hour before we turned it off.

Our adult children are our emergency contacts and they’d been contacted before the call had been forwarded to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (The Mounties) who had finally run us down on the lake.

Our second SAR event was on a long weekend as we were paddling through the marshes at the top of Lake Mulwalla on the Murray River in 2021. We emerged from between two islands to the sight of an approaching jet-ski. As the rider got close enough, he asked if we were the Dawsons. Now while we might have a big circle of social media friends, we’re not that famous and I’ve done little to achieve celebrity status with the jet-ski crowd. My eye’s went to the SPOT tracker5 I’d been carrying in the pocket of my PFD. Sure enough the SOS light was flashing. The rider on the jet-ski was the local police sergeant who was coming up-river looking for us while another boat load of State Emergency Services volunteers were coming downstream behind us. They’d all been called out on the long weekend to search for us. We apologized and showed them that the button was completely covered by a little protective flap which was in turn covered with some duct tape to prevent any accidental activation. Another leak and another alert. They were very good about it and the Police sergeant even joked that the look I gave him as he approached telegraphed “Who’s this wanker on a jet-ski?” I replied that there were redundant words in that question.

Again our kids had been contacted. Liam (#2) had told SAR that if we were moving we were probably OK and would be making our own way to an evac. Bree (#4) had been adamant that it was another false activation. She’d got all 6 alerts in 2019. Georgia (#1) responded to the family chat an hour later to say that she’d been shopping and had bought a new couch, and Riley (#3) hadn’t acknowledged any part of the alert until three days later.

Then we’d been accessories to another false alarm in the South East Tasmanian bush when a bright yellow helicopter had arrived above a shared campsite, landed nearby discharging a police officer and two paramedics who were looking for Dave. Dave was as surprised as the rest of the hikers at the camp, but soon discovered that the InReach device he was carrying had activated after being squeezed too tightly in his pack. Kate and I weren’t the only hikers who had checked their personal devices when the helicopter had paused to hover overhead.

The little hiccup in the green track on the above map was us pulling up on a sand bar to check all of our satellite messaging devices. We had one SPOT each, per the race rules, attached to the shoulders of our PFDs. I was carrying a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) which I’ve carried habitually ever since we had the first problem with the SPOT on the YRQ. Even though the PLB is fully sealed and designed for maritime use, it was in a vacuum sealed bag for extra protection. Our Iridium satellite phone, another race requirement, also had an SOS button which might have been activated by a squeeze or a heavy impact. An impact like one of the ones we’d taken while bouncing like a toboggan through the wrong channel at the entrance to the slough6.

A quick check of devices identified the culprit. The transmit light on the PLB was strobing. A burst or profanity followed. I had to tear the PLB out of its sealed bag to lift the button cover before I could long-press the button to deactivate the beacon. In my defence I’ll note that the instructions for activating the PLB start with un-clipping and extending the metal aerial to ensure it is able to transmit. The aerial in this case was still completely stowed, but the device had managed to transmit a signal all the way to an overhead satellite.

Rooting around in the back hatch, I pulled out the mandatory satellite phone, found the Race Director number (race requirement) in the contacts list and hit call.

Jon was not going to be happy.

Would we be penalized for this?

It went to voicemail. Jon was already on another call. I could guess who was calling.

I left a message saying we’d been buzzed, our PLB had activated, but we were not in distress.

Jon’s number two, Andy called me back almost instantly.

Andy is a man of few words and he remained frugal during our brief conversation. “OK, leave it with us, we’ll sort it. Bye.”

I stowed all the gear back in the boat and we continued down river. We now had something new to talk about… Which of the kids had been called? What had they done7? Would they have told SAR to ignore the call? Quite possibly.

We were still discussing the fallout from the activation in the final hours of the day when spied another team some distance ahead of us. It was clearly a kayak team, but there was also something clearly wrong with it.

We were gaining quite quickly on them and it was becoming easier to see why. They seemed to be in a bit of distress. Every few minutes they would stop and drift but not straight, they seemed to be continuously veering left. Not consistently though. Their rate of left-ness seemed to change from moment to moment. One moment they’d be heading slightly left, the next the left turn would become more exaggerated. Then they’d stop and drift again.

When they restarted, it looked like only the front paddler was paddling normally while the back paddlers seemed to be half asleep or possibly injured. An arm torn off by a bear would have been my diagnosis from 200 metres out.

We called out as we got close. It was Tim and Kiran from New Zealand.8

There’s a social contract that needs to be adhered to when somebody asks you “How are you?” that contract requires you to say, “I’m fine. How are you?”

Tim and Kiran were not fine, they had a compounding list of problems. The most significant was that Kiran had taken some medication to alleviate what sounded like motion sickness and it had left him feeling worse. He seemed to be having some trouble holding up his end of a conversation.

The starting premise of the Yukon 1000 is that teams are self sufficient and unsupported. That said, the nearest assistance for 95% of the race will be another team. Right here, right now, for Tim and Kiran, that was us. At least until we were sure they were OK.

We ran through their checklist of ailments, mostly with Tim.

Their GPS was giving them problems due to a low battery that they’d been unable to keep charged with their solar panel. There was possibly water in their connections or the GPS itself. They could only run it for short periods of time.

Then there was their rudder. It was pulling a bit to one side. Tim in the front seat didn’t have the rudder pedals so we pulled to their stern and had Kiran kick the rudder from left to right to see what was going on. The problem was immediately obvious. Tim’s hard right was a good right rudder. His hard left however, was not left rudder at all. His entire range ran from hard right to slightly right. It was hard to comprehend how they’d been drifting left with a rudder that had no left in it’s range. Their left-ness may have been the result of furious over correcting.

We chatted for a while and Tim told us they’d been paddling pretty well since day one of the race until Kiran had started feeling unwell. Tim told us they’d consistently been doing 220-240km a day9. We’d been doing 210-220km a day and here we were in exactly the same spot on the river. I thought Tim was hallucinating. The real explanation probably lay a combination of Kate and I having a trouble-free run down Laberge and our very direct route through The Flats.

They’d had a rough run down Laberge on day one with waves breaking over the boat. Their hatches had leaked, and the boat had developed submarine-like tendencies towards the end of Laberge. They’d had at least one capsize and swim. Like other teams, they’d had water in their hatches and some wet gear as a result.

Kiran seemed to be perking up as we spoke, so we were soon happy to continue on, leaving them to work out their rudder problems. It would almost certainly require a stop on a beach somewhere.

We ended our day on a wide silt beach 30 kilometres closer to Dalton than we’d been the previous year. We could see another team camped on the opposite bank a mile or so ahead of us. They’d already be set up when we landed, so they’d be leaving before us in the morning. Long Point, the massive oxbow with the shortcut we’d missed last year was just around the next bend.

There was no sign of any other team behind us, but we knew there were two kayaks and a unknown canoe team somewhere nearby. We resolved to start the next day on the stroke of six hours and defend whatever position we currently held with everything we had in reserve.

We were 76 kilometres from the finish. We’d probably reach Dalton before midday, depending on the currents we could harness.

This would be our last night on the river.

Despite the sore wrists, wet gear, minor blisters, less minor abrasions, an appalling odour, and general exhaustion, we’d miss it when it was done.

I was already missing the therapeutic rock that had been under my foam mat every night since Whitehorse. We’d pitched this last night on a silt beach that finally had no rocks. I suggested to Kate that if we collected a crate of rocks, came up with some mystic Oriental sounding name, and sold them in fancy boxes as some kind of new age miracle cure to back pain, we’d make a fortune. She answered with a loud snore.

I bashed my drybag of spare clothes into a shape that was vaguely pillow-like, cursed my punctured pillow, and went to sleep.

| End Time | 16/07/2025 23:39:48 |

| End Location: | 66°6’36.0720″N 148°38’49.9200″W |

| Altitude: | 98.0 m |

| Distance: | 177 km |

| Paddling Time: | 17:50:02 |

| Non-moving time: | 00:32:30 beached and in the shallows |

| Average Speed: | 10.3 kph |

| Max Speed: | 15 kph |

| Race Position: | 7th (up 2) |

Help encourage more posts by buying Steve a coffee…

Choose a small medium or large coffee (Stripe takes 10% and 1% goes to carbon reduction)

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Donate- At the end, we found out that the Boys had taken their canoe through the same narrow cut and had enjoyed themselves as much as we had. ↩︎

- Head on waves were hitting canoe paddlers in the chest that day. Several canoes capsized. ↩︎

- The race organiser later explained that if you tightened up the screws too tightly on the SPOT3 batter panel, it actually deforms the panel and causes it to leak. The SPOT4 has a very different design. ↩︎

- There are six buttons on the case of the SPOT3. Five of them send innocuous messages or turn things on or off. The least water tolerant one is the one that activates the cavalry ↩︎

- A new one which had been provided as a warranty replacement for the one that had leaked. SPOT insisted that it was an unprecedented failure. ↩︎

- Logic would suggest that it wasn’t the banging through the slough that had caused the activation. The nearest helicopter base would have to be 45 minutes to an hour away, so our activation must have been almost 90 minutes earlier. ↩︎

- We found out later that Georgia had taken the call this time. She’d assumed if we’d used the PLB it was serious. Our previous false activations had both been from SPOT trackers. She’d told SAR we were in the Yukon 1000 but nobody had the number, so they’d contacted Jon via Instagram. Hot tip for next year would be to give Jon’s satellite phone number to our emergency contacts. The rest of the kids found out later and were again dismayed that we’d caused them some inconvenience. ↩︎

- Kate’s mum in New Zealand had sent us a newspaper clipping about Tim and Kiran telling us that we might want ot try this race one day… ↩︎

- For the record, I’ve seen the GPS stats. They were indeed paddling further than we were almost every day. ↩︎

2 thoughts on “2025 Yukon 1000 – Day 7 – Wednesday”